The Failed Promise of the Internet

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield. And this is disgraced anchorman Howard Beale's live on-the-air tirade from the 1976 movie Network.

[CLIP]:

PETER FINCH AS HOWARD BEALE: We know things are bad — worse than bad. They're crazy. It's like everything everywhere is going crazy, so we don't go out anymore. We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller, and all we say is, 'Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and my steel-belted radials and I won't say anything. Just leave us alone.” Well, I'm not going to leave you alone. I want you to get mad!

BOB GARFIELD: Beale was raging against complacency, cheap titillation and the conglomeratization of everything, including the media.

HOWARD BEALE: I want you to get up right now and go to the window, open it, and stick your head out and yell, "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!"

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Writer Paddy Chayefsky’s vision was dark and prescient. Soon enough, two real-life broadsides came to prominence, articulating similarly bleak visions of our media environment. Culture critic Neil Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death, which observed that society was filling itself with narcotic drivel, along Brave New World lines, and disengaging sleepily from civic life.

Meantime, journalist turned academic, Ben Bagdikian, warned in his book, The Media Monopoly, about concentrated ownership's threat to democracy and spent years sounding that alarm.

BEN BAGDIKIAN: Of our 1600 daily newspapers, about a dozen corporations now control more than half of all national daily circulation. Of our 11,000 magazines with individual titles, a-half-dozen corporations have most of the revenues. Of our four television networks and 900 commercial stations, three corporations have most of the audience and the revenues.

BOB GARFIELD: The result, he said, was an ever-shrinking universe of media corporations protecting their lucrative marketplace by limiting the marketplace of ideas to establishment voices and a narrow set of views. It was all pretty scary, but then, just in time, came –

[VINTAGE 1990S VIDEO CLIP/”INTRODUCTION TO THE INTERNET"]:

SINGERS:

…on the internet!

Cyberspace, set free, hello virtual reality!

Interactive appetite! Searchin' for a website!

A window to the world, got to get online!

Take a spin, now you're in with the techno-set!

You're goin' surfin' on the internet!

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Not just the funnest ride ever, but the ultimate marketplace of ideas, the mall of America of ideas, the mall of the world of ideas, in which everyone has a voice and access to the information needed to guide a democratic society, as Vice- President Al Gore explained.

[CLIP]:

VICE-PRESIDENT AL GORE: This form of government became possible, according to many, only after the printing press distributed a sufficient quantity of civic knowledge to empower the average citizen to participate in the decisions that were necessary to guide the destiny of a great nation. If that was the case, then we can only imagine what advances for democracy lie in store.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: But instead of delivering infinite diversity, Gore’s information superhighway has been narrowed down to two lanes, Google and Facebook, which between them account for two- thirds of online advertising revenue, two companies, two-thirds. And people worried about Time Warner and the Walt Disney Company.

JONATHAN TAPLIN: This is not what, I think, the founders of the Internet wanted, but it's the world we've got.

BOB GARFIELD: Jonathan Taplin, director emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California, is author of the forthcoming book, Move Fast and Break Things, chronicling the damage wrought by the titans of Silicon Valley.

JONATHAN TAPLIN: And so, all of a sudden, what you have is a world in which there are two or three gatekeepers who have far more concentration of power then Walt Disney in its wildest imagination ever had.

JASON KINT: You know, the first half advertising revenue numbers, I think, best frame this.

BOB GARFIELD: Jason Kint is CEO of Digital Content Next, a trade association for premium digital publishers.

JASON KINT: The industry grew in the US advertising market for digital about $5 billion in the first half of 2016, and Google took about 60% of those dollars and Facebook took about 40%. So collectively, those two companies took 100% of the growth in the industry for the first half of the year. Facebook and Google, for the most part, don't create any content, and so, 100% of the growth in the industry is going to two companies that don't create any content.

BOB GARFIELD: But they do have an audience - of billions - and, as such, they are by far the biggest distributors of news and news-like content in the world. This has some benefits, beginning with the enormous reach it gives publishers and the shared ad income that comes with it. It also has some positively dystopian disadvantages, mainly the ceding of distribution to third parties who have no journalistic or civic mission, whatsoever. These tech companies’ interest is keeping you personally glued to their platforms, a motive that doesn't lend itself to feeding users with the latest on Aleppo, the Flint drinking water calamity or anything whatsoever taking place in your state house. What it favors is dresses that look golden white to some people and black and blue to others, or Kanye's nervous breakdown or “fake news.”

[CLIPS]:

ANNOUNCER: Welcome to the Hillary and Bill Clinton body count documentary. In this video, we’re going to discuss the 114 people the Clintons have killed to keep quiet.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Fake news, of course, is not a 21st century invention. Indeed, before the mid-20th century professionalization of newspapering and decoupling from party affiliation, it was a staple of the press since the founding of the Republic. But what is unique to our times is the filter bubble of our Google News and Facebook pages, which, like lazy parents, keep feeding us more and more of what we like, whether good for us or not. You don't have to be an ivory tower academic to see how this can contaminate the democracy.

[CLIP]:

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: And increasingly, we become so secure in our bubbles that we start accepting only information, whether it's true or not, that fits our opinions, instead of basing our opinions on the evidence that is out there.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE/END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Mind you, it’s not that a bunch of soulless Silicon Valley capitalists are personally making terrible editorial decisions to serve us French fries and tendentious lies. That job is done by computer algorithms - Facebook’s is called EdgeRank - that favor some content over others, based on so-called “engagement” - what gets liked more, commented on more, shared more.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Things have to push emotional buttons with a whole lot of strength to really carry through Facebook’s ecosystem.

BOB GARFIELD: Siva Vaidhyanathan is a professor of media studies at the University of Virginia.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: And the effect that it's having on us is clear. It is hurting our ability to operate as citizens in a republic. It's hurting our ability to make sense of the world. It's harming our ability to think through complex problems.

BOB GARFIELD: And it is devastating to publishers that do have a civic mission. This is an industry already reeling from the digital revolution, which reduced barriers to entry to nothing and created a ruinous glut of ad inventory. Since 1990, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US newspaper industry has shed almost 60% of its workforce, as revenue shrank by 72%. For all the lip service paid to doing more with less, the editorial cutbacks have been crippling. The population of statehouse reporters has halved since 1993 and half of those remaining work part time. Foreign bureaus are all but extinct. Many papers, including The New York Times, have even stopped routinely covering crime, fires and other quotidian calamity. Analog ad dollars of yore have been reduced to digital ad dimes. But even those increasingly depend on third parties because more than half of publishers’ traffic does not come directly to their home pages but via links in social media. And so, in cities around the country, in search of eyeballs and the ad revenue that comes with them, papers are scrambling to locate readers wherever they happen to be and to serve some content which most intrigues them.

[MORNING NEWS MEETING/SAN JOSE MERCURY NEWS SOUNDTRACK]

BOB GARFIELD: This is the morning news meeting at the San Jose Mercury News, eight editors around a conference table, others connecting via video link. The session begins, as always, with a rundown of what is trending on social media.

[CLIP]:

EDITOR: The Golden Globes were announced today, Susan Olsen, Brady Bunch actress, fired after a homophobic rant... and the December Supermoon.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Neil Chase is executive editor of the Bay Area News Group. He says the days of editorial mandarins dictating the news are long gone. Not only must the Mercury News take its content wherever the readers are, it must take it where the readers’ interests are.

NEIL CHASE: What’s trending, in terms of what's being talked about on other websites, not so we can do the same things but what are we missing, what are people talking about?

BOB GARFIELD: And if that means ending slavish adherence to a news agenda dictated by a calendar of government meetings and police reports, so be it.

NEIL CHASE: There are certain stories that we will cover whether or not we think they’re interesting to people, but there are also stories you look at and think, I don’t know if we really needed to cover that story, let’s have a thoughtful conversation about whether that's the kind of news we should be covering. The second layer is, what's happening on our site? Which things did well over the past 24 hours or over the past weekend? What got people's attention, what didn't because we didn't write the headline the right way or we missed something? And if we’re not thinking about every headline and writing it well, then we’re not getting that story in front of as many people as want to see it.

BOB GARFIELD: Which, in a click economy, is what keeps the lights on; stories that get seen generate ad revenue, however diminished. And maybe the reader will be drawn back to the newspaper's homepage, generating more page views. Maybe they’ll sign up for a newsletter or buy a reprint. Every little bit helps. And every little bit, Chase emphasizes, subsidizes the expensive and generally less lucrative nuts-and-bolts reporting at the core of the newspaper's mission.

NEIL CHASE: I know we will not be the 60-plus billion-dollar industry that we once were, nationwide, but if you can come up with new ideas, new models to offset the drop in print revenue, you’re keeping the business alive and stable and keeping the journalism happening for the people who need it.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: It is that very holistic view that in the past 16 months enticed publishers to make the counterintuitive decision to surrender distribution of their content to third parties. Instead of the stories residing on the publishers’ own sites, they live in the so-called “walled gardens” of Facebook Instant Articles, Google, AMP and Snapshot Discover, custom content handsomely designed and fast loading for mobile consumption. That’s because it's piped in direct and, thus, unladen with the layers of tracking code and irrelevant bottom-feeding ads that bog down so much online content. In theory, it's a win-win-win, better experience for users, exclusive content for the platforms and a bonanza for publishers who stand to enjoy both larger audiences and better ad rates that come with the tech platforms’ extraordinary targeting capacity. So, where could the flaw be in that?

Okay, so the Silicon Valley juggernauts keep all the new audience data for themselves, refusing to relinquish to publishers the very commodity that enables them to target directly. And, sure, the algorithms still favor the fluffy or the incendiary or the otherwise highly emotional over-reporting substance and, yeah, the algorithmic suppression of expensive-to-produce serious journalism creates a financial disincentive for publishers to spend on serious journalism, to begin with. But the money! [CASH REGISTER CHING] Yeah, that sucks too.

According to a Digital Content Next study, leaked by an association member to Business Insider, the average first-year revenue to publishers from third-party distributors was $7.7 million or only 14%, on average, of their overall income. Now, if you’re gonna sell your journalistic soul, shouldn't you get more out of the Faustian bargain?

Eamonn Store, until leaving this week for a venture in corporate social responsibility, was CEO of the Guardian US newspaper. Almost all of the value of this dedicated content, he says, accrues to the platforms, companies that operate in total opacity and have demonstrated little regard for the effect of the filter bubble.

EAMONN STORE: I think people at Facebook have a very real responsibility for, aside from whatever it was in the last quarter, 7 billion, I can’t remember, it was billions of [LAUGHS] revenue, with very little account for the way you are shaping the future of society. And I think New York Times is seeing this, the Post is seeing this, and others. If we do what the ad industry wants, we should create more fluffy stuff in safer territories and push it all through a pipe for a minimum amount of revenue and just try and deliver volume for low cost, right? That’s essentially what the ad industry is asking for. Senior agency people are telling their clients to avoid the Guardian because the news cycle is too – is, is too dark right now.

BOB GARFIELD: This, says Store, is the toll of putting –

EAMONN STORE: - way too much power with a very select group of people.

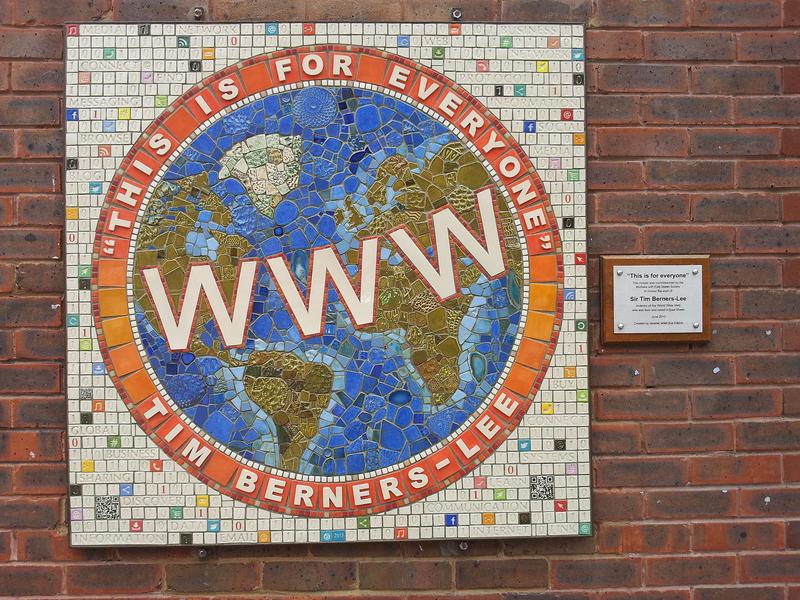

BOB GARFIELD: Media concentration is not just bad social policy, says Internet pioneer Tim Berners-Lee. It is bad architecture, antithetical to the history and healthy future of online life, quote, “Close to the principle of universality is that of decentralization, which means that no permission is needed from a central authority to post anything on the Web, there is no central controlling node, and no single point of failure.”

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

But if Berners-Lee is right, and Bagdikian was right and Vaidhyanathan and Taplin are right, and if the temple has been overrun by the moneylenders and partly for that reason a new dark period of political history has been ushered in, wherein too much power has, indeed, been usurped by a small number of people, the irony is thick. Back in the 1940s, the computer age itself was ushered in largely according to the ethos of the philosopher/mathematician Norbert Wiener, father of cybernetics. Wiener, says Stanford University Communications Professor Fred Turner, sought safe haven for democratic discourse in the wake of 15 years of fascism via the same architecture we now disparagingly call the filter bubble –

PROFESSOR FRED TURNER: - in which freedom was imagined as being able to build your own feedback loops, as being able to enter into the world, seek the information that you needed, learn from it and then change your action accordingly. In many ways, Google is the dream of Norbert Wiener from the 1940s realized. The trouble is, once realized, it doesn’t necessarily bring us democracy. It brings us a new and different mode of authoritarian enclosure.

BOB GARFIELD: An unintended consequence of utopian engineering, you might say, like genetic modifications going haywire in the wild or, on the subject of automating ourselves to death, Dr. Strangelove's Doomsday machine.

[DR. STRANGELOVE CLIP]:

PETER SELLERS AS DR. STRANGELOVE: - because of the automated and irrevocable decision-making process which rules out human meddling, the Doomsday machine is terrifying and simple to understand - and completely credible and convincing.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Convincing, like a dubious business proposition that sounds like a good business proposition, convincing, like an invented presidential endorsement from the pope in Rome, convincing, like cyber sirens luring us to their irresistible but fatal pleasures. Odysseus lashed himself to his mast to fight that temptation. Howard Beale became unhinged.

Us? Whether we wind up surrendering to the awesome power of the machine or raging against it, what we must do, at least, is be sure we understand its perils.

[ALI FARKA TOUCHÉ BY JENNY SCHEINMANN/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week show. On The Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess and Jesse Brenneman. We had more help from Micah Loewinger, Sara Qari, Leah Feder and Kate Bakhtiyarova. And our show was edited this week by our Executive Producer Katya Rogers. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Terence Bernardo. Jim Schacter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Brooke Gladstone will be back next week. I’m Bob Garfield.