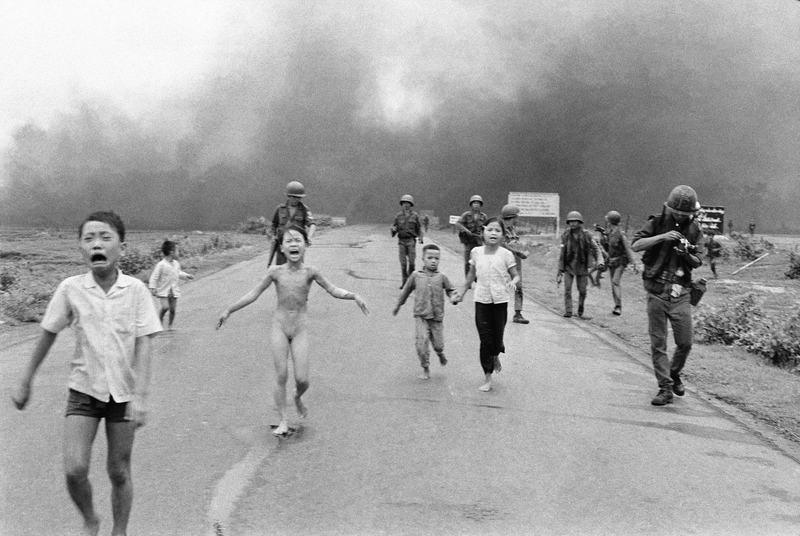

BOB GARFIELD: You know the image. It’s the iconic and horrifying Vietnam War photo, the napalm girl, of anguished 9-year-old Kim Phúc burned in a South Vietnamese bombardment, running naked down a road. Several weeks ago, Norwegian author

we author Tom Egeland shared the photo to Facebook in a post titled “Seven photographs that changed the history of warfare.” But when the photo hit Facebook, it was flagged as “child nudity” and automatically taken down. Norway's largest newspaper Aftenposten then wrote an article about what it called Facebook’s censorship, also including the photo, only for Facebook to take that down when the article started to make the rounds online. Before long, Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg was decrying Facebook’s editorial irresponsibility. And Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, sounding like Dr. Strangelove, was blaming it on the machine.

[CLIP]:

DR. STRANGELOVE: Because of the automated and irrevocable decision-making process which rules out human meddling, the doomsday machine is terrifying?

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Humans weren't at fault. It was the algorithm. This was exactly the opposite of the problem Facebook faced four months ago, where actual human beings were caught using their judgment in curating the Trending Stories part of Facebook’s newsfeed. Accused of liberal bias, the company scaled back the human touch and ceded more power to the algorithm. Damned if you do, damned if you don't.

Siva Vaidyanathan is a professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Siva, welcome back to the big show.

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: Thanks.

BOB GARFIELD: All right so, unquestionably, Facebook has changed human behavior –

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: - on a grand scale, very nearly an unprecedented scale, and they’ve certainly changed media consumption on a grand scale. And we’re dependent on them. Is it too much for us to ask for them to do a better job, since they are the filter through which we see so much of the outside world?

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: The problem is there's no single definition of “a better job.” We, the Facebook users of the world, are never going to agree on what a better job means. The way we got here, the way we got to almost 100% dependence on algorithmic judgments through Facebook. is that a few months ago Facebook got in trouble for just the opposite. Facebook had employed a number of editors, basically, people who helped make judgments within the newsfeed. Then Facebook gets accused of exploiting its own biases, which, of course, it was going to do. It had hired a bunch of college-educated Silicon Valley Americans to make editorial decisions for the world. That was not going to go over well with, for instance, many American conservatives.

So Facebook then undoes that decision and then tries to build and improve an algorithm to help us figure out what goes into the newsfeeds. And for a long time Facebook has had automatic flags on images that seem to portray human nudity. I don't think any of us want to argue that Facebook should remove those flags and those filters. And if that means that the photo of Kim Phúc disappears every once in a while from Facebook, it doesn't mean that Kim Phúc disappears from the world. The world is not Facebook. The world is not even Facebook plus Google. The fact is that it’ll never leave our consciousness and our history.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, one of the wrinkles here is that both four months ago when the kerfuffle over the editing out of some popular but, you know, crazy conspiracy sites and now with the Kim Phúc photo, people say to Facebook, well, you know, you’re the worst publisher ever. And they say, publisher, whaa, we’re not publishers, we’re a platform. What are they saying when they say that?

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: Yeah. So look, when Facebook or Google claim that it is a platform and not a publisher, it's appealing to a claim of innocence, a claim of neutrality, a notion that, look, it’s not us, it’s the computer, it’s not us, it's the algorithm.

BOB GARFIELD: They just repackage what's already out there. Is that a legitimate argument?

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: It’s never really been a completely legitimate argument, largely because algorithms are always the baked-in reflection of human judgment. No algorithm is neutral, no algorithm is innocent. When someone designs an algorithm, that person is making judgments and rendering them in the code. So, of course, it's editorial decision making one step removed from specific human intervention, but it doesn't mean that a company is not making editorial decisions, that a company is not actually publishing because, ultimately, the company does make yes or no decisions over certain content and it makes decisions about which content will be more prominent in people's feeds or results than other content.

BOB GARFIELD: This is not just a question of semantics, publisher versus platform. There are legal applications, are there not?

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: I mean, in the case of copyright and in the case of obscenity, platforms have pretty good protection against any serious claim of liability or charge of liability. They have the ability to merely get rid of the potentially offending material and never have it reach the point of litigation. But look, that’s true of a company we would never accuse of not being a publisher, like Slate. So Slate has ways for users to interact with Slate. Users can contribute some content, through comments, for instance, and Slate has a responsibility, when notified, to take down any copyright infringement or anything obscene from that particular site, right?

So all publishers and all internet service providers/platforms have that right and that responsibility, and it's pretty widely shared. So, yeah, the distinction between what is a platform or internet service provider, which is how the law usually distinguishes it, and a publisher has really eroded, if it ever really existed. Most big organizations both produce their own content and make their own judgments about their own content and host content produced by other people, so they basically share the same set of concerns.

BOB GARFIELD: So what's the moral of this story, Siva?

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: The moral of the story is when it comes to editorial judgment Facebook can never win but, in the long term, Facebook can never lose. If The New York Times consistently made ethical decisions that offended its readership, it would face tremendous punishment in the market and it would adjust. And that's what happens when we see The New York Times make such errors. But on Facebook, we use it for so many things, its usefulness is spread so widely and its culpability is spread so widely that anything like this incident with the photo Kim Phúc, anything that smells of censorship just comes and goes and Facebook keeps rolling on. It can never keep everyone happy, but it's in no danger of angering enough people to matter.

BOB GARFIELD: Siva, thank you, as always.

SIVA VAIDYANATHAN: My pleasure

BOB GARFIELD: Siva Vaidyanathan is director of the Center for Media a0nd Citizenship at the University of Virginia.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Coming up, why tribal lands are still terra incognito to many journalists. This is On the Media.