The Enduring Allure of the Library of Alexandria

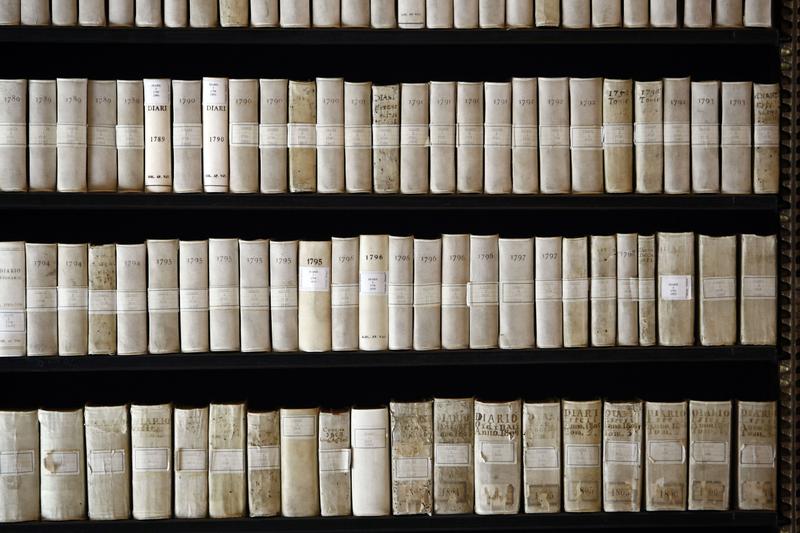

( Pier Paolo Cito / Associated Press )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last week, a popular website called Z Library, that gave readers access to e-books online for free, was taken down. One reader denied took to Tik Tok.

[CLIP]

TIKTOK The United States authorities taking down Z Library is essentially the modern day burning of the Library of Alexandria.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The burning of the Library of Alexandria is invoked whenever our access to books is lost or threatened. But for centuries, it's also inspired scientists and inventors, philosophers and programmers to envision or even build a better library. A perfect library. One that stocks every book ever written, the kind of library that may have actually existed once. On The Media producer, Molly Schwartz went to her local library to meet some of the people trying to build a universal repository of human knowledge, to learn what kind of progress they've made and what keeps the dream alive.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ It's a gorgeous fall Saturday in Brooklyn. Mild chill in the air. Colorful leaves. General good vibes. And I'm on my way to a birthday party at the Brooklyn Public Library at 9:30 in the morning.

[CLIP]

BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY Welcome, everyone, to Wiki Data Day. Today is Wiki Data Day, it's the 10th anniversary of wiki data. So Wiki data is sort of the data science side of Wikipedia.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ You know, Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia with millions of articles and hundreds of languages all written by volunteers. Jim Henderson is one of them. And today he's wearing two hats. Literally.

JIM HENDERSON This is the data hat, something I ordered when I was on the board of directors of the local club.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ The data hat says I heart Q60. Q60 is wiki data for New York City. On top of it, he's wearing a beanie that says Wikimania Capetown.

JIM HENDERSON When we had our next to last Wiki-mania worldwide convention.

JAMES FORESTER So we have this kind of mission statement for the Wikimedia movement.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ James Forester is a software engineer at the Wikimedia Foundation.

JAMES FORESTER Imagine a world in which all people have access to the sum of human knowledge.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Providing everyone on the planet access to the sum of human knowledge. That's the prime objective of Wikipedia, as stated by co-founder Jimmy Wales.

JAMES FORESTER I mean, it's a mission statement, right? You're not meant to achieve them. You're meant to move towards them. And definitely we've moved a huge amount towards them in the last 20 years — pushed the ball along the road a little bit.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ As the day goes on, I learned about Wiki Data properties and qualifiers. I also get in a little bit of trouble because On The Media's Wikipedia page isn't up to date.

[CLIP]

WIKI DATA DAY Add in Suzanne Gaber. Publish the changes, and it's done. You need some more links.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And I spoke with someone who's thought a lot about universal libraries and how they work.

RICHARD KNIPEL I grew up with the 1940s Britannica and 1960s World Book, and I wanted to contribute to the sum of knowledge.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Richard Knipel is the president of Wikimedia in New York City. But in the world of Wikipedia, he's known by his username Pharos.

RICHARD KNIPEL Named after the Pharaohs of Alexandria, the lighthouse of Alexandria. It's in homage sort of to the Library of Alexandria.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Perhaps the closest thing there ever was to a universal library, a bastion of all the world's knowledge for all who seek it.

RICHARD KNIPEL We actually had our international Wikipedia conference. We had Wikimania was in Alexandria a few years ago. And people do feel a strong cultural resonance with the Library of Alexandria and other universalizing attempts at knowledge.

ALEX WRIGHT For some reason, the Library of Alexandria has captured people's imagination, and it was certainly the largest library of its era.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Alex Wright is the author of the book Glut: Mastering Information Through the Ages. He says the Library of Alexandria was built in Egypt in the third century BCE, likely by decree of the pharaoh Ptolemy the First.

ALEX WRIGHT And he tried to attract as many notable scholars as he could to come and contribute to the collective enterprise of building not just a library, but a university and a center of learning.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Ptolemy's mandate for the Library of Alexandria was as ambitious as it was simple: collect everything. Every papyrus, scroll, every book, every manuscript. By force, if necessary.

ALEX WRIGHT When ships would come to Alexandria, officials would basically seize the books on the ship and add them to the library.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ They lifted books from private citizens, stole them from docked boats, and allegedly took books by a subterfuge from Athens. But despite the Ptolemy's best efforts, Alexandria could never really compete with Athens. Athens was this organic center of culture and learning, whereas in Alexandria, all the scholars were entirely beholden to their employer, the Pharaoh. So as the Ptolemaic empire crumbled, so did the library.

ALEX WRIGHT There's this deeply intertwined relationship between libraries and state or governmental power, and you find that the great libraries of the world have not coincidentally emerged alongside powerful empires or civilization.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ What happened to the library is actually unclear. Some say Julius Caesar burned it down. Others say a conquering Muslim commander burned the books. And others say that the library never succumbed to a fire at all, but rather to years of neglect and changing empires.

ALEX WRIGHT We don't know for sure exactly what happened. We do know for sure that the library no longer exists and that the 500,000 odd volumes of material there have, for the most part, been lost to posterity. And yet there's something apparently kind of energizing about that ideal that has inspired a lot of people over the years to try to work towards some kind of universal repository of recorded information.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Versions of Universal Libraries, Pepper Science and Speculative Fiction. From Jorge Luis Borges’s Magical Library of Babel.

[CLIP]

MAGICAL LIBRARY OF BABEL The universe, which others call the library, is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To Isaac Asimov's Imperial Library and the Foundation series.

[CLIP]

LIBRARY AND FOUNDATION An Imperial Library on Chancellor Stacks, I'm assuming, was Wooden. There are all these marble busts.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To Douglas Adam's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

[CLIP]

HITCHHIKERS GUIDE TO THE GALAXY The Hitchhiker's Guide has already supplanted the great Encyclopedia Galactica as the standard repository of all knowledge and wisdom.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To the TV show Doctor Who.

[CLIP]

DOCTOR WHO The library. Every book ever written. Whole continents of Jeffrey Archer and Bridget Jones. Monty Python's Big Red Book.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ There's even a universal library in the world of the occult. According to Theosophists.

[CLIP]

THEOSOPHIST The Akashic Records is a place within a different dimension. It's a higher dimensional energy that is like the library of the universe. It holds all the records of the universe. And anybody can tap into this energy, into this knowledge, and access it for themselves.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Around the invention of Gutenberg's printing press. The Vatican Library was also founded. According to Pope Nicholas the Fifth. The goal was ensuring, quote, “for the common convenience of the learned. We may have a library of all books in both Latin and Greek that is worthy of the dignity of the pope and the apostolic sea.” And then in the late 19th century.

ALEX WRIGHT Suddenly printing of books became a industrialized mechanized affair.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Alex Wright.

ALEX WRIGHT And you start to see this explosion of popular literature, magazines, what they sometimes called penny dreadfuls, these cheap little precursors to tabloids.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ It was during this explosion of books that people started paying attention to how to organize and retrieve them using universal classification systems.

ALEX WRIGHT That was when Melvil Dewey invented his decimal classification. There was another guy named Charles Cutter, worked in the Boston Atheneum who developed a different classification system that's now used in a lot of academic libraries in India. There was a librarian named Ranganathan who developed a really highly sophisticated method that he called “faceted classification.”

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And then in the 1930s, with huge leaps in technological progress following World War I came another burst. This is when the visionary H.G. Wells published a series of short stories. In them, he explained a concept called “The World Brain.”

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP There is no practical obstacle, whatever now to the creation of an efficient index to all human knowledge, ideas and achievements through the creation that is of a complete planetary memory for all mankind.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Around the same time. Paul Uplay, a librarian in Belgium, envisioned the world book.

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP Here, the workspace is no longer cluttered with any books in that place. A screen and a telephone within reach over that an immense edifice are all the books and information. Cinema, phonographs, radio, television. These instruments will in fact become the new.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And Vannevar Bush, who worked for President Truman as what was effectively the nation's first science adviser, wrote about a memory supplement that he called the Memex.

[CLIP]

VANNEVAR BUSH The analytical machine, which will supplement a man's thinking that which will think for it will have as great an effect as the invention of the machine. Way back to the load off of men by giving them mechanical power instead of the power of their muscles.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Basically, these imagined groundbreaking gizmos are proto computers and proto search engines. They were all invented and more and better. And with all of this came another round of optimism starting in the 90s and picking up speed in the aughts and 2010s that the dream of a universal library could be realized via the Internet.

BREWSTER KAHLE I'm a librarian, and the idea of using technology is perfect for us.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ That's Brewster Kahle, again, the founder of the Internet Archive, who we heard from earlier in the show.

BREWSTER KAHLE I think we can one up the Greeks and achieve something. Yeah, we could actually achieve the great vision of everything ever published, everything that was ever meant for distribution available to anybody in the world that's ever wanted to have access to it.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ There was a host of these projects all at the same time because people all had the same vision. Put books online. There was also the Universal Library Project, which was later largely supplanted by HathiTrust, which is this massive cache of digital content that's available to a group of research libraries. And then there are projects ranging from the World Digital Library to the Digital Public Library of America and all kinds of smaller offshoots.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Walk into the Bear County Digital Library in San Antonio, Texas, and you'll see plenty of screens but zero books. This doesn't look like a library.

NEWS REPORT No.

NEWS REPORT That's the point.

NEWS REPORT That's the point.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ But the one that probably had the grandest vision, the most top down, the most completist, was the Google Books project. Google transported truckloads of books to their massive scanning centers across America, and they got their technology good enough that they were scanning about a thousand pages an hour. Since 2004, they've digitized over 20 million books, and they had plans to literally digitize every book in the world. Google Books was a huge deal. The company's first moonshot, the first salvo in a revolution.

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP What is being discussed tonight is not your ordinary kind of revolution. Like cars and jets. It is a super revolution, like writing and printing and computers.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Google Books were sued by the Authors Guild for violating copyright. Ultimately, Google won, but only because they only show snippets of most books. A far cry from the initial vision of universal access.

GYULA LAKATOS Unfortunately, I'm still using a mobile Internet plan.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Gyula Lakatos is a software engineering consultant. He lives in a house. On a hill in a small town in Hungary, on the banks of the Danube, too far from Budapest to get high speed Internet. And that's a problem, because he's working on a very large project housed in two servers stacked behind him.

GYULA LAKATOS One of them is running 20 hard drives. The other one is 10.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Lakatos is using those servers to save just a little bit of today's digital flood for posterity. Inspired by deep admiration for the ancient empires of Greece and Rome, and fearful that modern civilization will suffer the same fate as those lost knowledge centers.

GYULA LAKATOS As far as I know, only around 1% of books and documents survived from classical antiquity.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Which made him wonder what's going to be left from life today?

GYULA LAKATOS So I created an application suite. It's not just 1 to 7 applications. You can deploy these applications to crawl the web.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ He spent about $6,000 on equipment that ran his applications for two years, amassing over 90 million documents onto the servers in his house. His application suite is open source and available on GitHub, and you'll never guess what it's called.

GYULA LAKATOS It's called Library of Alexandria.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ At this point, he's collecting around 2 million documents a week. They include everything from interesting, complex doctoral dissertations to the kind of ephemera of restaurant menus to a weird collection of Russian passports. It's a mishmash of the valuable and long forgotten all hoovered up and stored in the hills of Hungary. Lakatos wants to open up his treasure trove to the public. But for now, it all just lives on his servers because he's afraid about copyright laws and navigating copyright laws for 90 million documents. That's a job for more than just one person.

GYULA LAKATOS I don't really want to host it, to be honest. I'm a lazy person. I just want to search in that library. That would be a lot of fun.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ I came across the Lakatos project on a subreddit called Data Hoarder. It's a forum for people with a kind of unusual hobby, trying to preserve things they find on the Internet. They hoard this data in their living rooms and corners of the web, and sometimes on places where a lot of the web is hosted — Amazon Web Services or AWS. It's all to try to preserve a first draft of history for the future.

GYULA LAKATOS Humanity in general can lose a lot of knowledge out of nowhere for no reason. Imagine that, for example, a fire is starting in one of the AWS warehouses, that a lot of things are hosted and people just lose their data. Like the whole Data Hoarder subreddit is very concerned about this and I just wanted to kind of notify people with this name a little bit or warn them a little bit more.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ I appreciate these data hoarders. I got my degree in library science because when I stood in the rare books room at my university, I felt a sense of awe, like I'm part of a story that began long before I was born and will go on long after I'm gone. I hope. In the glut of information, more gets lost than saved. And that's not always a bad thing. One of the first things an archivist learns is that the best way to save things is to know what to throw away. Have you ever noticed that the material on which knowledge is stored has gotten more ephemeral over time, from carved stone to parchment to paper to tape and floppy disks to drives for outdated devices, to everything stored in a cloud. Prey to all kinds of terrestrial and cosmic events. The fact is, preserving all the world's knowledge is like building a dam against the unyielding torrents of time. It's impossible. But if we don't keep trying, how will anyone know we were ever here?

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For On The Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.