BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Depending on your tribe, there was either a blue wave, a blue rivulet or whatever the president says. In the realm of ballot initiatives, however, there was less ambiguity. Americans in states across the country voted for the progressive option on matters repeatedly blocked by the Trump administration and the Republican Congress.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Marijuana was a big winner in the midterms. Look at Michigan, 56 percent of voters supported legal recreational use and possession of pot for the people over the age of 21.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: And the citizens of Idaho, Nebraska and Utah are now requiring conservative states to accept Obamacare's Medicaid expansion.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: And in a historic move in Florida voters, have restored voting rights to 1.4 million people with felony convictions.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But if Mary Jane, Medicaid and the Fourth Amendment were a few of the night's big winners, the big loser was planet Earth. Several key climate change initiatives were handily voted down, including an ambitious proposal in Colorado.

[CLIP]

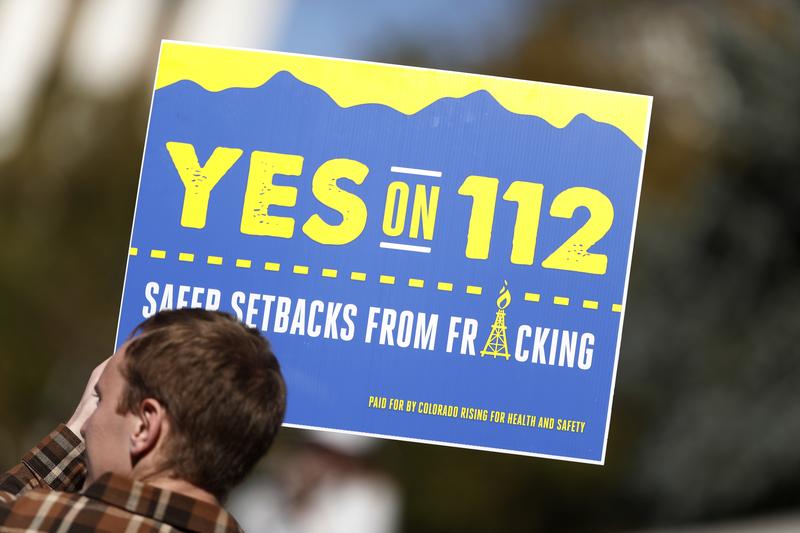

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: If passed it would result in the heaviest restrictions on fracking in the country known as Prop 112. It would increase the distance new well sites can be located from such places as schools and homes. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Kate Aronoff a contributing writer for The Intercept, has been tracking the path of two of those propositions. She says the forces arrayed for the battle over Proposition 112 were unusually lopsided.

KATE ARONOFF: The oil and gas industry outspent the people who were pushing for it by 40 to one. So they spent about 40 million dollars to fight Proposition 112. And the folks who were pushing for it had about a million dollars.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How big was the campaign to support the proposition? I mean, how much grassroots support was there?

KATE ARONOFF: Pretty massive. For almost a decade now, folks who live near fracking sites, near sites of oil drilling, they have been fighting for, you know, even just basic protections. I spoke to some folks who live in Weld County which has the highest concentration of drilling in the state. There are 23,000 wells there. Colorado as a whole, has 50,000. And just in Weld County there are infant mortality rates twice the rate of surrounding counties. And so one thing they fought for was to change the existing set back requirements so that it would include, not just occupied school buildings with things like playgrounds and soccer fields. And that got rejected in the legislature. So this is kind of like a last resort measure after years and years and years of pushing for basic common sense demands.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Who were the anti-Colorado proposition people?

KATE ARONOFF: Almost overwhelmingly oil and gas interests. They published a lot of TV ads. They knowingly misled the public.

[CLIP]

VOICEOVER: I keep people safe and productive. That's why I oppose Proposition 112. It's bad for our economy. It'll cost our friends and neighbors their jobs and it doesn't improve safety.

VOICEOVER: Proposition 112 is an extreme and misguided measure that will effectively ban natural gas and oil in Colorado. [END CLIP]

KATE ARONOFF: They kept calling it a ban on fracking, despite the fact that they saw a study which said that it would still give them access to about 61 percent of oil and gas reserves in the state.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That's still a loss.

KATE ARONOFF: Forty percent. It's a little easier to talk about this now that the measure now has not passed. This would actually represent a threat to the oil and gas industry. But the science on climate change is manifestly clear that we need to get off fossil fuels as quickly as possible. That will involve some measure of job loss for workers in those industries. And part of the reason why in the next proposal we're going to talk about. They have such an emphasis on job creation, it's just sort of acknowledging that our economy has to look a lot different if we're going to deal with this problem. And that's a question, you know, for any climate policy that passes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Tell me about Washington state initiative 1631. I mean, this would have been historic. It would have been the first statewide carbon tax like measure in the country.

KATE ARONOFF: This would have levied a 15 dollar per ton tax on polluters in the state, per ton of carbon dioxide. And it would use that revenue to focus on a couple things from job creation to forestry programs to sort of sequester carbon and preserve natural land. Investment in communities that have been most impacted by the fossil fuel industry and by climate impacts. This is crafted over the course of years, actually, by the coalition of groups who came together to make a model program.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Apparently the fight against this ballot measure was also historic. The most expensive in state history.

KATE ARONOFF: Yeah, so they were outspent by a slightly smaller ratio than in Colorado by about two to one. And the campaign for 1631 actually did have some larger money backers– Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg– but the sheer force of the fossil fuel industry and the oil and gas sector in particular, just bore the full weight down on us.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Here's an ad that summarizes all the arguments it seems against Proposition 1631.

[CLIP]

VOICEOVER: It's a complicated poorly written proposal that's filled with unfair exemptions that make no sense. It's supposed to reduce pollution but it exempts many of the state's largest polluters. Big corporations get a free ride while Washington families, consumers and small businesses are left to pay billions under 1621. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did she say anything wrong.

KATE ARONOFF: I don't think so. Haha.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Haha.

KATE ARONOFF: I mean, that's a complication of this policy. This came from a really sort of massive coalitional drafting effort. And I don't know kind of what decision was made to exempt people like Boeing from these. I mean, the line they give–and I think there's truth to this–is that industries which are exposed to a lot of foreign trade, would be worst hit.

KATE ARONOFF: Exposed to foreign trade? The idea is that if a company deals a lot in international markets, industries like steel, that buyers of their products will just go elsewhere.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Because of the cost?

KATE ARONOFF: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So despite the fact that it was so hotly fought and so expensively fought, I mean there were inherent problems with this proposition.

KATE ARONOFF: I think the industry is being a little misleading when they lead with the exemptions. And part of that is because I emailed BP when I came back to this story a couple of weeks ago and I asked, you know, BP supports carbon pricing at the international level.

[CLIP]

BP CHIEF ECONOMIST SPENCER DALE: We know from basic economics, if you don't like something the most efficient way of trying to ration it is you put a price on it. BP has a strong view that, part of that transition to a low carbon energy system, one of the most efficient ways of doing that is putting a meaningful price on carbon. [END CLIP].

KATE ARONOFF: Right before the Paris climate talks. BP was one of six major oil companies to send a letter calling for a global price on carbon. And this seemed to be kind of a disparity there, right?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How much did BP put into this fight?

KATE ARONOFF: They put about $13 million in.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In fact, BP even has a web page positively devoted to the topic of carbon taxing.

KATE ARONOFF: That's right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why did they fight this proposition so hard?

KATE ARONOFF: So the first line they gave is this exemption. The third point–and I'll get back to a second one–was that it would make it harder to pass the type of policy they would like to see. The second–and I think this is the key–is that it wouldn't exempt them from any regulations.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wouldn't exempt them from any regulations. So what you're saying is that BP really likes carbon taxes. But at a price. And the prices exemptions from pollution standards.

KATE ARONOFF: That's right. And so the leading proposal in this vein right now is a proposal from the Climate Leadership Council. This is a plan drafted by a kind of a who's who's of Reagan and Bush era cabinet members which would levy a higher price on carbon than what would have happened in Washington. In exchange, for that the fossil fuel industry would be exempt from climate liability lawsuits–like the one that just happened here in New York–the charge that Exxon misled its shareholders about the risks it faces from climate change. So it would be exempted from that and it would also kneecap the EPA ability to regulate carbon.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Really? That is a high price for a carbon tax. So we have a new house, we have some people who are very climate minded in there. What do you expect to see?

KATE ARONOFF: I think if we do see a real push for federal legislation it will be a matter of the people who are really out front on this just being sort of incessantly uncompromising. And, you know, it may well not get through Congress in the next two years while Republicans control the Senate, but I think something really positive that could happen is that ambitious legislation does get through the house. There is a sort of strong enough campaign for that and the failure of the Senate to do anything about this has kind of shown to be just totally obvious and confirmed for everyone that they are unwilling to do anything about this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The question is does that bother enough people?

KATE ARONOFF: We can hope. And I think part of this is reframing how we talk about climate change. And so not having it be a matter of gases in the atmosphere and sort of far off effects, but talking about climate change in terms of what kind of job can it give you in the next couple of years? How can doing something about climate change also improve your quality of life by, you know, providing robust public transit, that would build up green infrastructure. Fixing the MTA is a climate demand, to be specific to New York. And so kind of broadening what we think of as quote unquote climate solutions and reorienting the conversation away from we all have to give up straws and plastic bags and that we're all sort of guilty consumers just complicit in this crisis to actually talking about the ways doing something about climate can raise everyone's standard of living.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ahh, so I see. So we use a different terminology instead of calling it climate change we call it infrastructure.

KATE ARONOFF: Haha.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Haha. Thank you so much.

KATE ARONOFF: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Kate Aronoff is a contributing writer for The Intercept.