Crediting the Researchers Who Told Us About Omicron

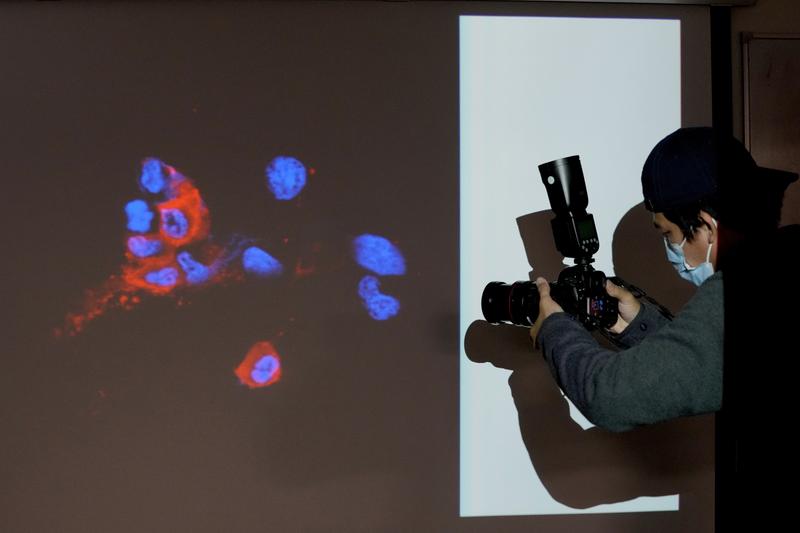

( Kin Cheung / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. While we await more news about Omicron, let's remember how we learned about this new variant in the first place. Scientists across the globe detected it and promptly told us. On November 22nd, a Hong Kong public health researcher shared the genomes of a new coronavirus variant to the Global Initiative on Sharing all Influenza. A database community otherwise known as GISAID. The next day, Dr Sikhulile Moyo submitted more data on Omicron on behalf of the Botswana Harvard HIV Reference Library, shortly followed by Dr. Tulio de Oliveira, who uploaded data on behalf of his team at the Center for Epidemic Research and Innovation in South Africa. And in response...this.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The US, Brazil, Australia and Indonesia are among countries to bar travelers from southern African nations. Japan has banned all foreign arrivals. Morocco has halted all inbound flights and Israel has closed its borders for two weeks.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The quick response of those early data collectors clearly were given their due by a grateful planet.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

STEPHEN COLBERT We're all lucky that South Africa alerted us to the dangers of all Macron and thanks to them. The White House issued a ban on travel from eight countries in southern Africa. So far, it's only been found in the southern African countries of Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Oh my God, that's most of it's a small world.

NEWS REPORT As you hear from African nations, specifically South Africa, saying that they feel like they're being discriminated against, that they're being punished for making sure that their science is up to date and for making sure that they can detect new variants. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE President of South Africa Cyril Ramaphosa.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT RAMAPHOSA The only thing the prohibition on travel will do is to further damage the economies of the affected countries and undermine their ability to respond to and also to recover from the pandemic. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Some outlets didn't even credit the researchers in Hong Kong, Botswana and South Africa, who detected and shared the news about Omicron.

JEREMY KAMIL The very first reports in the news that came out were in the Guardian and Newsweek, and they failed to mention any of the names of the researchers who discovered the variant who did the work. Sequencing the viruses, collecting patient samples.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jeremy Kamil is associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport.

JEREMY KAMIL They failed to even mention that this data came from the GISAID sharing community, which has been getting this really important data to save lives to flow from places like Brazil, from places even like Iran or countries that don't get along with the United States very well, like Russia. Those countries also share via GISAID, and they share rapidly, and we are one humanity, whether we like it or not. These viruses show us time and time again that they don't really have much respect for borders. They'll make you sick and they'll kill you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But what difference does it make? Whose name gets checked in an article? Given the stakes here, why should we care?

JEREMY KAMIL If you don't recognize those who provide something valuable to humanity, in this case, giving vaccine makers a head start, saving lives, producing that new recipe that's going to protect you from Omicron. Then there's a very significant risk that that work won't continue happening because the people who are doing it aren't going to get the acclaim that they deserve in their countries. And so the people above them are going to say, Hey, you shared this data from our universities effort funded by these mechanisms in our country. Yet all the acclaim is going to a researcher in San Diego or someone in London or Cambridge, England, and instead of us getting credit for it, we've got rewarded with the travel ban. So now the prime minister and the public are angry at us and our funding agency who gets money to support your work is having its budget cut because of the travel ban. So all this sharing is just punishing us and then the neighboring countries that are just learning to sequence and detect new variants sooner. Their political leaders are going to say 'stop it.' Sequencing creates variants and travel bans. It doesn't do anything good for us. And then what happens is a lot like what happened with Delta. It took months to find out that there was a new variant. If folks in India or whatever region around India where it may have first emerged, we know it is probably Southeast Asia, the virus emerges and spreads very far, and there's a long latency. So some researchers maybe sequence it and then they keep the data on their computer. They're going to put it into the public domain at some point, but they're going to wait to get their paper accepted so that they get formal recognition for their work and in a public health emergency, that's a recipe for disaster.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So in the coverage of the Omicron variant, compared to say, Alpha, which was first detected in the U.K. The U.K. scientists and researchers got credit, but in this current case, you mentioned the public health researcher in Hong Kong, Alan K. L. Tsang. You've also talked about others who have played a key role and didn't get credit. Dr. Moyo and his team in Botswana, you say, played a key role, and De Oliviera in South Africa also played a huge role. But particularly the South Africa team have been getting the blame for the variant. What's the nature of the blame?

JEREMY KAMIL It's just a typical protectionist response. Political leaders are probably afraid that they'll be voted out of office. You know, what did you do to prevent this variant from getting here, and we often see a double standard. I mean, cases have now been announced in England and Germany, and you hear their leaders talking about how we have it contained. We don't need a travel ban in Europe and oh, it's already here. So don't worry, but they aren't talking about removing the travel ban against South Africa or Botswana.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mmhmm.

JEREMY KAMIL You know, there are probably special circumstances where a travel ban would make sense. But we are about two years into this pandemic and we've had time to develop tests. We've had time to develop vaccines, and we really need to think about the cost benefit of punishing countries who released data quickly because it's very likely that this variant did not start in South Africa or Botswana. It likely started in some other under-vaccinated areas of Africa, and we failed as a global community, especially the wealthy countries in the global north, to share our vaccines with countries in Africa and other lower and middle income countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia. And that's let the virus run rampant there, and we know that when the virus gets into, say, an immunocompromised person and there's a lot of cases of HIV/AIDS, sadly, in sub-Saharan Africa that are not well treated or treated at all. So when the virus gets into people who have decreased immunity, it can sit around for a lot longer time and persist. The immune system comes on slowly and weakly. And so the virus has a more comfortable training camp to develop a countermeasure against, say, an antibody that neutralizes the spike. And so we see an example of many different changes that accumulated. Another theory is that Omicron evolved in maybe some kind of animal reservoir and spilled back into humans from those animals. We do know this coronavirus spilled really easily into mink and in North America into white tailed deer. There may be some species of animals in Africa that were infected, and then it spilled back into, say someone who interacted with an animal in some way or another. But in any case, we don't know that this virus actually emerged in these countries that we're punishing. We just know that these are the countries that share the data rapidly and are doing a good job sampling people in their communities. Sequencing the virus that's making them ill and sharing that data with the world. And you know, there's that saying no good deed goes unpunished, and I think this is a very good example of that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you give me an example of what happens when researchers don't get credit for their work or face backlash for their discoveries?

JEREMY KAMIL I look at a country like India. The history of how they've been treated by Great Britain in Europe has made that country very protective of data that comes from India, and so their government has a culture of being very protectionist and ensuring that there's significant benefit that comes back to India if they release data and that if they generate data that all the collaborations are within India. And the researchers there that I've spoken to, they really want to work with researchers in the West, they do tell me, be aware that our hands are a little bit tied. We don't give away Indian data to Western researchers. That reaction is there for a reason, and it came from how they were treated for decades. It causes significant risk to us in the context of where new viruses come from. We know that new variants of Ebola don't crop up on the Harvard Medical School campus in Boston. They don't crop up on the campus of Oxford in the UK. They tend to crop up in places that are off the beaten path that are former colonies, places like Botswana. I mean, it's great to have someone from Oxford or the excellent Christian Anderson from the Scripps Research Center help us understand evolutionary theory of these viruses, and there's definitely a place for Westerners to chime in. But we do have to give credit where it's due. We really do. If you want to keep seeing these data, it's just critical. There's hundreds of stories where people and former colonies or poor countries were in essence totally disregarded and swept aside, both in the scientific literature and the media coverage. And it's literally writing their names out of history. And it's really sad and destructive thing. And I think in the pandemic, it couldn't be clearer that there's a real cost and risk that you can count in human lives. I mean, imagine if we didn't know about Omicron, we didn't have GISAID, we didn't have Sikhulile Moyo, we didn't have Tulio de Oliveira, we didn't have Alan Tsang in Hong Kong. Moderna and BioNTech would be two or three weeks behind in updating their vaccines. Those are two or three weeks slower that we're going to have shots in arms of the most vulnerable people, even in our rich countries that we've been so selfishly successful at protecting. So it should be in our latent self-interest to address this problem, starting out by acknowledging the people who do. A work.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jeremy, thank you so much.

JEREMY KAMIL Thank you for having me on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jeremy Kamil is Associate Professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport. For a full list of the researchers in Hong Kong, Botswana and South Africa who swiftly shared their data on the Omicron variant. Go to onthemedia.org. There, you can also find our latest Breaking News Consumers Handbook: Variant Edition, all on one printable page and all the other breaking news consumers handbooks too.

Coming up, most of us are actively engaged these days in avoiding death, but some seek it and find it quite literally out of reach. This is On the Media.