Every Story Has A Twin

( New Directions Publishing )

********** THIS IS A RUSHED, UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT *************

BOB: This is On the Media, I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Amid the coverage of the refugee crisis in Europe, many reporters have sought to chronicle the individual stories of people, enroute. They’re trying to convey both a particular set of circumstances, and our common concerns, our shared priorities: family, shelter, food...dignity. Essentially, these reporters are striving to put directly before us, the voices of people telling their own story, the voices we rarely hear.

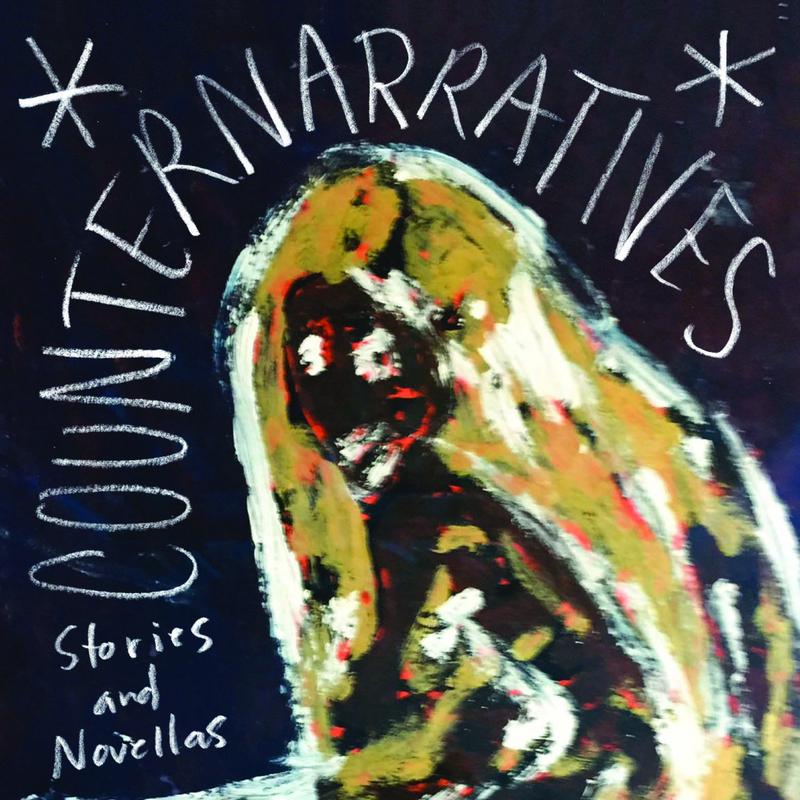

Enter Counternarratives, a new collection of short fiction by writer and poet John Keene. In these luminous and layered tales, Keene conjures the voices of people at the margins of history, and puts them at the center. “History never happens in isolation,” says Keene. “Every story has a twin.”

KEENE: I was very interested in histories that are totally hidden, totally buried, totally obscured. Counternarratives are working against historical master narratives, and they play overtly with the writing of history.

BROOKE: Keene locates these “twin” stories: in the tale of a slave who blithely disregards his constraints; in the spiritual and sexual union of two poets during the Harlem Renaissance; in the experiences that motivate an African dictator’s nihilistic brutality. Keene is always challenging our assumptions. His characters are not acted upon, or only acted upon, they are the actors. They choose to flee, or fight, and even, in one story, to very nearly...fly....

KEENE: So in a story like Acrobatique, a real historical figure that we’ve really never ever heard from... Miss LaLa, the subject of Edgar Degas’ famous painting, actually gets to describe her initial encounter with the person who memorialized her.

BROOKE: And we get to encounter her.

KEENE: Exactly.

BROOKE: The painting is Degas’ 1879 work titled “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando.” You’ve probably seen his rendering of a small, strong young woman, suspended high in the atrium of the Parisian circus, by a rope between her teeth. For 136 years she’s been frozen in that moment, silenced by that rope, but Keene puts us inside the head of Miss La La, AKA Anna Olga Albertina Brown, or in reference to her mixed race, Olga the Negress, the Venus of the Tropics, the African Princess...

KEENE: Imagine this woman, in the late 19th century, who really was so extraordinary, she was such a superstar all over Europe, and she’s captured in this iconic painting and many people know of the painting, but almost no one ever asks the question, “Who is Miss La La?” The entire story is one continuous sentence. Here Miss Lala is actually talking about letters that she writes back to her family

BROOKE: Letters of a life so foreign, so exalted and dangerous for her and her performance partner, her family cannot really respond.

ACROBATIQUE: ...and we prayed like Catholic girls to the saints that there would be no accident -- there wasn’t, though their letters in return never mention those bits 1, nor do they repeat a single word about all the other things, how I intend to spend every waking hour in the air, to soa r with the brio of a sparhawk and glide with a sparrow’s ease and float, as Kaira and I do, as the audience perches on the tips of their seats, with the lightness of two creatures who have fully emerged from the chrysalis, how I want to suspend the entire city of Paris or even France itself from my lips, how I aim to exceed every limit placed on me unless I place it there, because that is what I think of when I think of freedom, that I have gathered around me people who understand how to translate fear into possibility, who have no wings but fly beyond the most fantastical vision of the clouds, who face death daily back out into the waiting room, and I am one them…

BROOKE: Probably Keene’s most talked story is “Rivers” because we have such a strong identification with its twin. It’s the personal story of Jim Watson - the escaped slave from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

KEENE: Reading this story as a young, African American junior high, high school student, was a somewhat traumatic experience. I loved the story, but I was also deeply disturbed by the story. And it was very difficult to come to terms with until I was much older, and then I think was able to really appreciate what Mark Twain was doing. But I was always fascinated by Jim, and Jim’s life. Because he’s so integral to Huck’s experience, and yet we learn so little about him.

BROOKE: In “Rivers”, Jim, here called Jim Rivers, is interviewed by a journalist who wants his take on the events in Twain’s novel. The story begins with Jim thinking what he doesn’t want to talk to the reporter about - the two times he’s seen Huck since the events of Twain’s book. Once again we are in the head of a character, who we know, but never really knew,

KEENE: ...I realized I wanted to tell Jim’s story, but of course the sort of natural inclination would be to focus on Huck and Tom Sawyer, and so I thought how could I tell the story in which someone wants Jim to tell that story, but he tells another story, which would have been the story of my, I guess, great-great grandparents or people like them, living in places like Missouri, the upper south, so all of things did kind of fit together, and then I bring Huck and Tom Sawyer back.

BROOKE: Jim encounters Huck and Tom long after the events on the river. As Jim considers what he isn’t going to tell Tom and Huck, we’re hearing what’s going on in his head.

RIVERS: I think to conclude to the Sawyer boy and Huckleberry, all adulted now, that I keep that certificate at all times and in all places against my chest in a leather pouch I bought for myself and it reads JAMES ALTON RIVERS, FREE PERSON OF COLOR, a resident or citizen of the State of Illinois, at all times in all places, and entitled to be respected accordingly, in Person and Property, at all times in all places, in the due prosecution of his - my - concerns, at all times in all places, signed with the Seal of said Court, at Chicago, on the 23rd of November, in the year of our lord one thousand eight hundred and fifty-two…

...and I have carried it all the way up to and through the time I returned to Missouri, settling here in St. Louis since I was not ever going to set feet again in Hannibal if I could help it, and even when some of the Hannibal people including those LaFleurs have happened upon me down here there is not a thing they could say or do because I had the states of Missouri, Illinois, and the federal government on my side, though I’ve always made sure to have an escape route and a safe house on the other side of the river ready to flee to given the trials the courts are putting Mr. Dred and Mrs. Lizzie Scott through.

Instead I said, “I was living in Chicago for a few years then I decided to come back home. I posted my bond to stay here, have been working steadily and decided to settle down.”

“Chicago,” Sawyer said, looking at Huckleberry, “sounds like old friend has gone and got pretty fancy on us. What do you think about that, Huck?”

“I been as far south as Mississippi and over to Louisville, Kentucky but I never been to Chicago myself,” Huck replied.

“All kinds of things going on up in Chicago,” Tom said.

“Jim ain’t said nothing about all that, just that he been there and come back here,” Huck said.

“Some go to Chicago and get ideas,” Tom said.

The angles of that face, like broken porcelain, pulled apart and recombined until I almost did not recognize him. “Well, sounds to me like Jim is keeping himself out of trouble, and the worst thing for anybody these days is getting caught up in ae, getting involved with people like Lovejoy or Torrey or that new agitator writer Mrs. Stowe what likes to stir up a whole heap of trouble, too.”

BROOKE: Keene Counternarratives take many forms: some are told through diaries or letters; or spoken dialogues, or internal monologues. One story unfolds as a 72 page footnote to a fictional encyclopedia. In the piece called “Persons and Places,” Keene presents two narrations side by side: on the left, the very young W.E.B. Du Bois, who would become a renowned intellectual and activist, and on the right, his Harvard instructor, George Santayana, the influential Spanish philosopher.

KEENE: I was very interested in thinking about the relationship between these two very, very important figures. Dubois was a student of Santayana, and in some of the biographies of DuBois and also in Du Bois's writing, he talks about studying with Santayana, because it was a big deal, because Santayana was a major figure in American philosophy. In a really strange and enchanting memoir that Santayana wrote called Persons and Places, he talks about his time at Harvard, and he mentions many students but strangely he does not mention the student who first of all would have stood out, just physically, but also who went on to become one of the major figures of his time. So I thought, what might that first encounter between these two people look like.

BROOKE: In this excerpt DuBois speaks first, then Santayana, each describes passing the other on a chilly autumn afternoon in Harvard Square.

DUBOIS: Why does he glower so? Is it fear, for certainly he has seen a Negro before, or can it be an acknowledgement of how deeply we are linked? Or does he, like nearly all the rest of them, not really see me at all? Of course there will be scant possibility of a friendship. Be he a Latin or the Statue of Liberty; for even Professor [Wm.] James, in all his eccentric allegiance, admits, when we are at the same table, of those unshakable walls that separate us. Still I know that at some point soon I shall have opportunity to probe his mind, share my inquiries - he and I alone, in an upper room - and he will come to appreciate our common humanity.

SANTAYANA: This jeune philosophe, like the other Negro students, the handful of unassimilable Easterners, Chinese, Mexican boys, must by necessity subsist on an island even more remote than that which I sojourned on during my College days, within this larger crimson archipelago. At one level, I imagine it would provide a place of refuge and some element of happiness for their small and scorned society.

He observes me as if he has already examined the catalogue of ideas and impressions which I shall tell him when we eventually speak, of the gulf between the true-self and the world outside and how the mind, through its exercises, bridges it; of the forests rising around the language of the physicist’s thought; of the importance of doubt in the philosophical method; of the fugitive joys and sincere ecstasies - that heaven that lies in the heart of the earth; of my own long and unfolding exile.

BROOKE: Keene wanted to have DuBois and Santayana, talking to each other…

KEENE:... but not exactly hearing each other. So the columns don’t touch. And yet they’re side by side, so there is this sense of connection and contiguity; these lives are unfolding in parallel, they are, like the columns, looking at each other, but they have not yet found the language to speak to each other. And it probably would have been the case that DuBois would not have just approached Santayana based on the social codes of that era, but we get the sense that Santayana knows who DuBois is, and slowly but surely, those two columns, those two voices are going to come into communion but not just yet.

BROOKE: I'm wondering how you view the role of fiction here. In Counternarratives, it seems to function as a kind of antidote to history - a way to rebuke it or correct it through the poetic imagination.

KEENE: Fiction, I believe, has tremendous empathic power. I think some of the most recent studies in neuroaesthetics are showing this, in psychology, cognitive studies are showing us the power of fiction, and narrative in general to shape our perceptions, and stories offer us a way to enter other bodies, other spaces, and help transform our own perspectives. So I think fiction is extraordinarily important and powerful.

BROOKE: I know you wrote your own memoir of growing up in St. Louis... You have written the memoirs of people who never existed. It's almost as if the twin to their story, in one sense, is your own.

KEENE : Exactly. In my first book, Annotations, which is a memoir, it's also a novel, it could be read as a long poem, it's sort of a hybrid of all these different genres. It was very much about my own experience, about the experiences of people my age, a little older, a little younger, growing up at a particular time, at a particular place - particularly black, and in my case queer, but many have told me after reading it, that it resonates for them, even though their experiences were very different.With this book, I wanted to step outside myself and to really think more broadly about the people who came before me, before us, and to try to tell their stories. And so I saw that as a deeply ethical act, and I hope that I've done all of them justice.

BROOKE: John Keen’s Counternarratives is an elegant reminder of the countless hidden histories yet to be uncovered, as well as those we still choose to ignore. Maybe that’s what the fiction in Counternarratives can encourage us to do: to seek these kinds of stories, so that they don’t have to exist solely in our imagination.

CREDITS

BOB: That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Kimmie Regler, Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman and Sam Dingman. We had more help from Alex Friedland. And our show was edited by…Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Greg Rippin.

BROOKE:We had more help from Terrance McKnight. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for news. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB: And I’m Bob Garfield.