BOB GARFIELD This is On The Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD Imagine the paparazzi closing in on the biggest star in the universe. No, even bigger, much bigger than the biggest star.

[CLIP]

SHEPERD DOELEMAN In April of 2017, all the dishes in the event horizon telescope swivelled, turned and stared at a galaxy fifty five million light years away.

BOB GARFIELD That was Harvard astrophysicist Sheperd Doeleman at a press conference Wednesday for the National Science Foundation, preparing the audience for the money shot.

SHEPERD DOELEMAN And we are delighted to be able to report to you today, that we have seen what we thought was unseeable. We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole. [END CLIP]

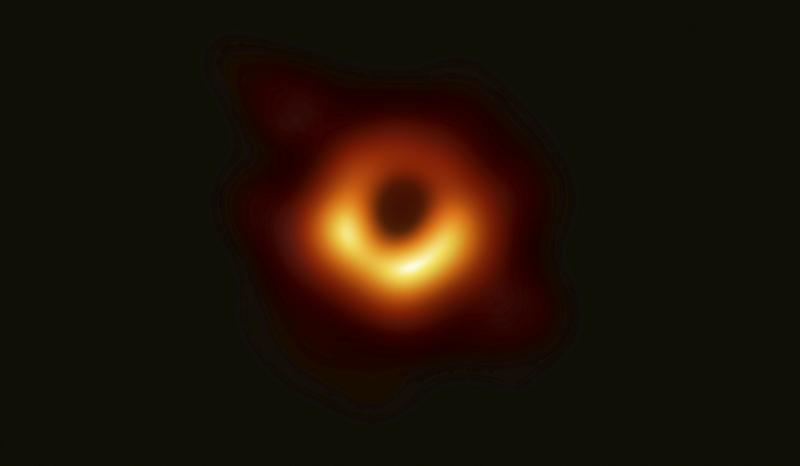

BOB GARFIELD An image of the densest of celestial objects hitherto only imagined because its gravitational pull is so fast that not even light can escape its grip. Yet, there it is in living color with the light at the very frontiers of its gravity field literally bent around its massive invisible self to define its contours. If we're being honest, it looked like a fuzzy glowing cosmic bagel. But to a scientist's eye--

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN You know, I really had a bit of a wow moment when I saw it.

BOB GARFIELD That's Priya Natarajan, professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University, who saw not a bagel but a revelation in the tradition of Galileo destined to reframe our sense of the universe.

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN Galileo was a pioneer in the sense, right? He, through the telescope, he looked at the moon and he recorded it. So for the first time you just didn't have a fleeting memory of an object that you saw but you had a record of it.

BOB GARFIELD I want to ask you about this whole notion of a material image shifting our perspective. In 1968, one of the Apollo astronauts William Anders, was in the spacecraft orbiting the moon and he snapped a picture. It captured the gray horizon of the moon in the foreground and in the sky hovers the blue and white planet Earth itself. What was the impact of this photo that came to be called Earthrise?

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN It was the first time that we were able to see the earth without being on the earth and it made us realize how vulnerable we are. We are all inhabiting this little blue marble that is sort of suspended in the darkness of space. I often say that it sort of brought home, I think, a sense of how significant and insignificant we are as human beings. It's significant because we develop the technology and the possibility to do this. Whereas, we are insignificant because it kind of brings into sharper focus that, gosh, space is littered with a lot of rocks. We just happened to be one. So it's a very emotional moment. It generated a sense of cosmic responsibility and a collective sense of cosmic responsibility.

BOB GARFIELD Here's some tape of Buckminster Fuller, the philosopher, mathematician thinker, creator of the geodesic dome.

[CLIP]

BUCKMINSTER FULLER People say to me I wanted to be like to be on a spaceship. And I say to you, you don't really realize what you're doing because everybody is an astronaut. You all live aboard a beautiful little spaceship called Earth. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD I want to ask you about the Hubble telescope which has yielded this vast trove of images. Here was ABC's Peter Jennings in 1990 talking about sending that satellite into space.

[CLIP]

PETER JENNINGS Tonight, finally, the space shuttle Discovery is in orbit. In its cargo bay waiting to be put into its own orbit a telescope so powerful it can see a dime 25 miles away. An instrument bound to contribute to a reassessment of the universe. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD Now the images that it would retrieve including the pillars of creation photos of the Eagle Nebula. They are jaw dropping. But do they fit into this conversation we're having because they're also kind of like abstract expressionist. You know they look alike, oh I don't know, illuminated glasses, not like the moon.

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN Right? So all these Hubble Space Telescope images are taken in different wavelengths and then they're combined and they're rendered in color. So they do represent very faithfully what is really there actually. So for example one of the most recent iconic images from the Hubble has been you know a very, very deep look at this set of objects, like six objects, called clusters of galaxies. There are about a thousand galaxies held together by the gravity of dark matter. And you know that because you see a lot of light bending just as we saw the extreme light bending around the black hole. So you know the Hubble has played a very important role but also it spoiled us with these incredible images because, as I said, the optical has a very strong pull. It's an evolutionary impulse because that's what we can really sense.

BOB GARFIELD We discuss the fuzziness of the image. It could be a black hole, you know, or it could be and out of focus bagel. Do you expect this image that gave you such a rare and emotional response to be the latest in a series of iconic images that reframe human understanding of the cosmos? Or in this world of rampant anti-science sentiment just fodder for the next imbecilic meme in the culture wars.

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN The rampant denialism of science now is extremely disturbing and I personally believe that one cause for that is the fact that the public does not understand the process of science. So I think the press conference where, you know, there was a very nice exposition of how things work, how they actually designed the project, how they got it to work, what they did in order to produce this image. Sort of demystifying this process, I think, is really what is needed and they convey the provision ality of science. That anything that we know is the best to date. It's apt to change if we have more data, better data, more evidence. And I think part of the problem is, you know, you have a lot of studies that are very poorly done so, you know, they say well coffee is good for you and then you know a month later of coffee suddenly bad for you. And these are just statistically not significant studies. So you know a lot of not so great science out there that is being fed to the public. I think that confuses the public because they don't know how to calibrate. But I think something like this, I think it can be reset because as I told you I'm an optimist. That's what I'm hoping.

BOB GARFIELD One last question. This whole conversation has been premised on the idea that a tangible evidence of the cosmos helps us as humans frame our place in the universe, frame our very humanity. As we begin to document dark matter, black holes, things that are unseeable and in many ways unknowable. How do you think that will change our own narrative of humanity?

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN What it really reveals is the power of the framework of science that we have developed. This way of making sense of reality using data and evidence. That, it's quite remarkable right because we have a brain that's basically the size of a cantaloupe and we were able to figure all of this stuff about the universe. So I think this is a revelation and a moment to take stock of what all we are capable of. And I think that touches everybody not just scientists.

BOB GARFIELD Priya, thank you very much.

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN Thank you so much.

BOB GARFIELD Priya Natarajan is a professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University.