BOB GARFIELD: The GOP maneuvering of 1964 and the shadowy Democratic sabotage of 1972 are both modern cases of nominee jiggering. But for the example that may hold the best clues to what's happening now, we offer for your consideration the election of 1824, which presented four candidates, one, that's right, just one party, and the mother of all backroom deals.

DANIEL FELLER: And the result was something approaching total chaos.

BOB GARFIELD: Daniel Feller is a professor of history at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. He lays out how campaigns in 1824 were rather different from today, in that candidates didn’t actually – campaign.

DANIEL FELLER: An idea going back to the American Revolution, really, and to the fear of executive power is that somebody who wanted the presidency enough to actively seek it, probably, for that very reason, was a dangerous man who shouldn't have it.

BOB GARFIELD: Another difference, the early parties, the Federalists and the Jeffersonians, were unorganized and the electoral system was in need of serious tweaking. As it was, a presidential contender could end up as his opponent’s vice president or pitted against his own running mate, both of which happened to Thomas Jefferson. Something had to change.

DANIEL FELLER: And so, the question is how you decide on one candidate. And they hit upon the idea of a caucus of party congressmen in Washington. Let them decide who the party's candidate should be.

BOB GARFIELD: So the congressmen and the caucuses would pick their party’s candidates and on Election Day the states would vote for either the Federalist or the Jeffersonian. Only problem was after the War of 1812, the Federalist Party pretty much dissolved, leaving just one functional party, which at first was a bit of a relief.

DANIEL FELLER: A lot of people were, were happy to say good riddance because it still held to that ideal that a president ought to be not a representative of a faction but a representative of the nation, like George Washington.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The prospect of a world without competing political parties led one newspaper to call it “the era of good feelings.”

DANIEL FELLER: Well, it wasn't an era of good feelings, and the problem is that parties may have gone away but political disagreements didn't go away. So by 1824, the only mechanism at hand for deciding who’s coming next is this old congressional caucus, but now that there's no Federalist Party if you decide things in the congressional caucus that means the congressional caucus is effectively deciding who the next president’s gonna be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

DANIEL FELLER: And the people are gonna be left out of it altogether.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was it about 1824 that made people say, it's time to upset the apple cart?

DANIEL FELLER: The idea that the people really ought to elect their leaders was sweeping the country. It's implicit, you might say, in the Declaration of Independence, in the idea of the United States as a republic but it was now coming to fruition; it was becoming real. More and more states were providing for a popular vote for presidential electors. More and more states were empowering at least every adult white male to vote. So the idea of democracy by 1824 is very much in the air. And the idea that a handful of congressmen in Washington are gonna pick the next president didn't go down well.

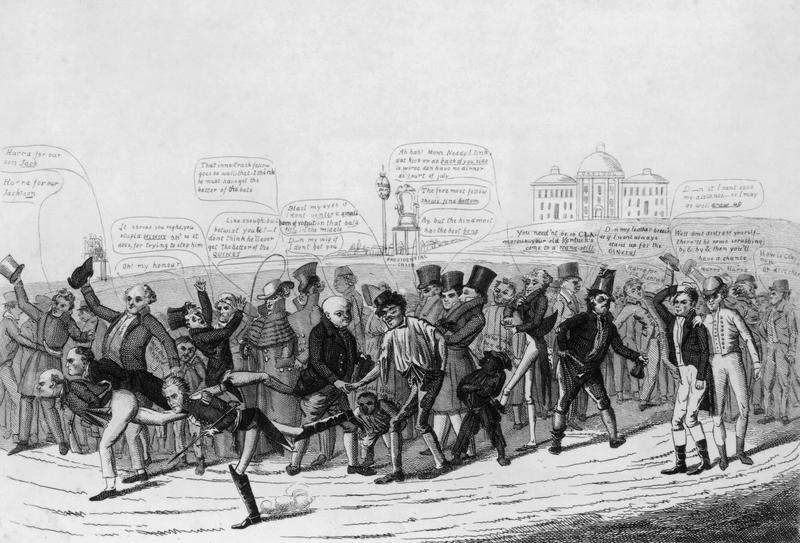

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Which is why in 1824 three additional candidates opted to run against the caucus pick of William Crawford. They were House Speaker Henry Clay, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and war hero, Andrew Jackson. Adams and Jackson both ran as outsiders but whereas John Quincy Adams was the consummate politician, roughhewn Andrew Jackson was not.

DANIEL FELLER: Jackson wasn't so much attacked as, in the early stages of the campaign, kind of dismissed for the reasons that he did not seem to have the, the vitae, the resume, the qualifications, the background of a statesman.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He hadn't served as secretary of state, he didn't speak any foreign languages, he'd never traveled abroad. In short, he was not the kind of person that was supposed to become president. But the people loved him. And when it came to the election, Jackson won the electoral vote but not the presidency, due to the fact that he had only received a plurality of the votes, not the required majority.

DANIEL FELLER: So under the Constitution, the election went to the House of Representatives. What happened is that before the House voted, Henry Clay, who was out of the running but was speaker of the House and had a great influence, announced that he was going to vote for Adams, on the grounds that Adams, like him or not, which Clay did not, was fit to be president of the United States, whereas Jackson was just, in Clay's words, “a mere military chieftain.”

What happened next is that Adams appointed Clay secretary of state, and that's when Jackson hit the roof and called it a “corrupt bargain,” partly because the Clay people and the Adams people had gone after each other fairly viciously during the 1824 campaign, so this looked like a bargain that could only be explained in terms of corruption.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What happened then after 1824? I mean, we have a phrase called “Jacksonian democracy.”

DANIEL FELLER: Jackson ran for president in 1828 as the people's vindicator, even the people’s martyr after 1824, and he famously enunciated the idea that the country is supposed to be run for and by you and me, not banks and corporations. And Jackson originated that language in American politics. This is why the populists, why the New Deal Democrats, why the Great Society Democrats all venerated Jackson.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So essentially, the corrupt bargain that denied Jackson the presidency in 1824 backfired big time.

DANIEL FELLER: That's correct. Almost immediately, the 1828 campaign, which began, you might say, the day after the House elected Adams, was framed as a two-man contest, a national two-man contest, and that was new, and, on the part of the Jackson people, as a campaign to - you might say, to recapture American democracy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did 1824 ultimately give rise to the two-party system we have today?

DANIEL FELLER: Yes. Immediately after the House selected Adams, all of the people who were angry and frustrated about the result – that not only includes the Jackson people but also the Crawford people - coalesced behind Jackson's candidacy in 1828. And in 1828, you had, for the first time really, a national two-party popular contest for the presidency.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The first time?

DANIEL FELLER: Yes. There had been contested elections, seriously contested elections, but first, in most states, there was no popular vote at the time. By 1828, every state, except one, had a popular vote.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

DANIEL FELLER: So by 1828, you can vote for president, and it was a campaign conducted on a national stage. And so, solving the mess of 1824, the chaos of 1824, down to a two-man national contest, paves the way for those two personal presidential campaign coalitions to kind of solidify into national parties, which they did over the next few years.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Being a historian, do you see anything historic in the fight over the process that we’re seeing right now?

DANIEL FELLER: I think we are still living in the shadow of 1824, in that if there was a message from 1824, and there was, it was virtue resides in the people, corruption resides in Washington. I think it’s largely because of that that there's never been an election that's gone to the House, since 1824.

What's happened in the 20th century, with the advent of presidential primaries, is that this idea that the people's will must not be thwarted has expanded outward from the election to the nominating process. And so, now we are having people react with horror to the idea of a brokered convention, in the same way that 1824 taught them to react with horror to the idea of a brokerage election.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Daniel, thank you very much.

DANIEL FELLER: Thank you, it’s been a delight.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Daniel Feller is a professor of history at the University of Tennessee and director of the Papers of Andrew Jackson.

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, a loophole that may allow campaigns to collude with super PACs. [LAUGHS] I mean, there ought to be a law!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.