The Complications of Weight and Covid

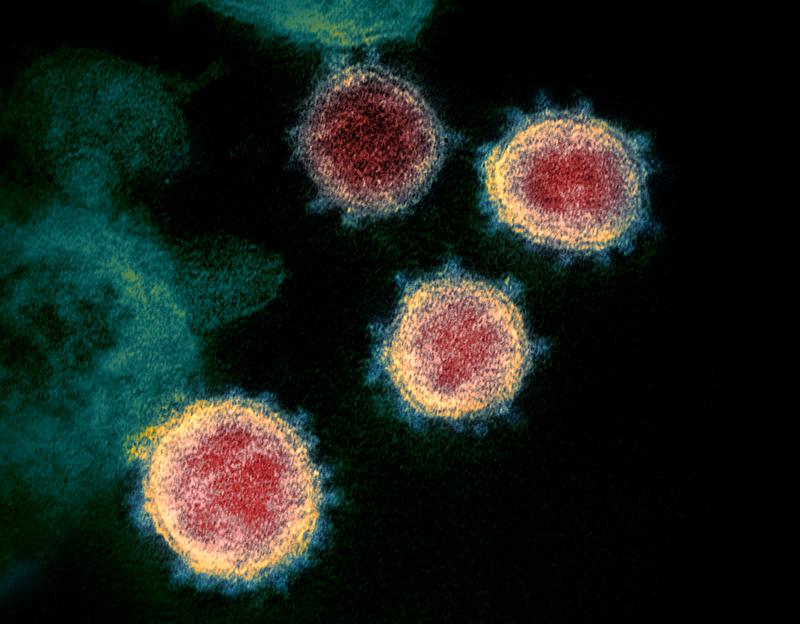

( NIAID-RML / Associated Press )

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. From almost the moment coronavirus began sweeping our shores in the spring of 2020, one group of Americans was declared to be among the most at risk no matter their age, medical history or general healthiness.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Before you open that pack of chips. Numerous studies link obesity to a higher risk of serious illness from the new coronavirus.

NEWS REPORT The overweight need to seek solutions.

NEWS REPORT It can double your chances of hospitalization and increase the risk of landing in intensive care by even more. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Pretty stressful for the three quarters of Americans whose BMIs mark us as overweight or worse.

[CLIP]

WOMAN I am overweight and I think I need to lose a bit of weight, so that in case I get infected, I'm not in the danger zone. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Soon, the damning data followed.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT A study by the World Obesity Federation finds almost 90% of COVID deaths are from countries with high rates of obesity.

NEWS REPORT Because fat is a metabolically and hormonally active organ literally in the body in terms of that tissue may suppress the immune system. Mechanical reasons makes it harder to ventilate or breathe.

NEWS REPORT The surprising part is that governments haven't really acted until now. So now we have this perfect storm of obesity Pandemic and a covid pandemic.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Perfect is a word best avoided in science, especially since a deeper look into the storm surrounding weight and COVID reveals rather imperfect conclusions.

Like how one of the first CDC reports linking BMI to worse outcomes from COVID didn't control for existing health issues — everything from asthma to cancer. Or like earlier this year, when a paper published by Harvard Medical School, professor Fatima Cody Stanford found that for patients with and without obesity, the Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines provided similar protection – in clinical studies, not in the real world. “Why?” you may ask — a key question we'll consider this hour, but not the only one. We'll also consider how fat figures in culture and politics, in medicine and history. But first, fat in the pandemic.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF What we know for sure is that obesity is associated with an increased risk of more severe cases of COVID and an increased risk of mortality. What we don't fully know is why.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Earlier this year, I spoke to Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa. He says that in looking for reasons why patients carrying more weight might more often experience severe COVID, we could be missing explanations that have nothing to do with biology.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Maybe people with obesity have differences in the way their bodies respond to this infection from an immune response or from an inflammatory response. But there are other possibilities which might be more feasible, which is that perhaps, we are treating people with obesity who have COVID differently than we treat others.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What leads you to think that?

DR YONI FREEDHOFF With H1N1, which occurred over a decade ago now, people with obesity, just like now, were found to have higher risk of death and more severe courses of H1N1. However, after the fact, it turned out that patients with obesity were provided with antivirals later in the course of their disease. When they controlled for when antivirals were provided, there was no increased risk any longer as a consequence of their obesity. There's precedents in general that people with obesity are treated differently by the medical profession. With respect to COVID, they may be treated differently in terms of whether or not they're admitted to the hospital floors, when they're provided with medications, when they're transferred to the ICU or in mechanical efforts like proning, which is putting a patient on their stomachs. Patients with obesity might require more hands to help to do that, and it's certainly not a consequence of any physiology if their proning is later in the course of their disease during the more severe surges of COVID. There's also the issue that patients with obesity, who likely have experienced discrimination by health care professionals, may present later in the course of their disease, which might affect their treatment course as a whole.

BROOKE GLADSTONE They present later because they don't want to rush to the doctor.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF We know that patients with obesity do tend to avoid interactions with health care professionals if they have had experiences with weight bias. Weight bias is highly prevalent in society as a whole, and the medical profession is part of society. Things have improved a great deal over the course of even my career, and I went to med school in the 1990s, but there's still a lot of work to be done that's for sure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What is obesity?

DR YONI FREEDHOFF It's a fair question. Unfortunately, right now, the way we think of obesity is just a simple measurement — whether it's the number on the scale or the number on the body mass index table. It has been stated that people with obesity have body mass indices greater than 30. The thing is, is that scales do not measure the presence or absence of health, and the body mass index table — it's literally a measure of bigness, not a measure of health.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now, it's funny. I have a cat, an unusually large cat. Everyone is always commenting on the size of the cat. But when I took him to the vet, I said, Is there a problem? He said, "Like obesity" and I said, ``Yeah.” And he said, “No, he's just a big cat. He's like a football player.”

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Football players are a great example. Over half of the NFL would be describable as having obesity on the basis of the BMI table.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Obviously, there are a lot of conditions that are associated with being overweight, type two diabetes being a big one. This is real.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Oh, no question. And so knowing that there is a heightened risk of developing type two diabetes at body mass indices greater than 30 is important for physicians and patients so that we can test and monitor for that in case it were to occur. But it isn't a guarantee that it's going to occur, nor should it be presumed that a patient who's coming in with a particular medical problem has that problem simply consequent to their weight, which sadly happens both at the hands of medical professionals. But also I've seen patients themselves attribute their concerns to their weight when really their concerns were not weight relatable.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So let's get to the Edmonton Obesity Staging System, which seems to be a far more useful way to determine how weight might influence a person's health.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF So this is a scale or a staging system that was published and developed in 2009 by Dr. Azaria Sharma and Robert Kushner. What it looks to do is to consider whether or not a person's weight is in fact having an impact on their health or quality of life. And we use that staging system, by the way, here in Canada to help triage patients as to whether or not they need, for instance, bariatric surgery. So going through the stages briefly, somebody with stage zero obesity would have no physical symptoms, no functional limitations, no psychological symptoms. Nothing who I would not describe as having obesity in the sense of how people tend to understand obesity today. They do not have a medical concern as a consequence of their obesity. I may discuss things like lifestyle with them, but I discuss those things with anybody at any weight.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So the Edmonton Obesity Staging System uses the BMI to establish a baseline and then drills down on the symptoms.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Yeah, so let's say you have a BMI of 30 or 31 or whatever you would be described as having class one – that's the World Health Organization Obesity classification – stage zero obesity. If you were coming to see me to say, you know, should I be trying to lose weight, I would say no, unless it's affecting you in some other way. But stage zero truly has no effect. So I'd be strongly encouraging this person to keep on living their life the way they're living it.

At EO stage one obesity would be somebody with subclinical risk factors. So pre-diabetes, slightly elevated liver enzymes, borderline hypertension, or they might have some mild physical symptoms or mild impairment that they ascribe to their weight. We would not, again, describe this as a person who urgently needs any sort of medical attention. Stage two, we would have some established weight, responsive medical conditions. Type two diabetes, sleep apnea, high blood pressure, moderate functional limitations in a person's daily activities. If we go up to the Edmonton Obesity stage three, they'd have significant problems and organ damage because of their diabetes or heart failure. Coronary artery disease with infarctions. Medicine’s really bad at saying why a person has something. There's plenty of people with BMI less than 30 with coronary artery disease. We can never really say why. What we can say is that people have conditions that are responsive to weight loss, high blood pressure, diabetes, etc.. Finally, there is stage four — severely disabling functional limitation, end stage organ damage. An example might be somebody who's got a BMI extremely high and is in a wheelchair because they're unable to ambulate because of their arthritis hyperthermia, which they're not getting enough oxygen where weight loss might make their ability to live their lives better. If we think about the staging system, we're just trying to describe how severe the impact is that is possibly attributable to a person's weight or excess adiposity.

BROOKE GLADSTONE When was the Edmonton Obesity Staging System developed?

DR YONI FREEDHOFF It was developed in 2009.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In response to the uselessness of the BMI by itself.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Yes. Once we started to control for whether or not a person's weight was affecting their health, suddenly we saw that, for instance, people with an EO score of zero with higher BMIs were not found to have a higher risk of mortality compared to the general population.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I'm sure that some listeners are thinking, okay, so grouping people by BMI isn't perfect, but we lumped together people in lots of big categories for research, for gender, race, age, income. We know that these groups are not monolithic, but we can also control for these things in research to try to find real odds of a disease.

Why is it so hard to control for weight? Is it because we don't control for implicit bias?

DR YONI FREEDHOFF That's exactly it, actually. So, for instance, looking at the various studies on COVID risks, they do control for a whole host of things. But weight is a monolith. Society has been trained to believe that weight automatically carries risk. Society has not been trained to believe that there is systematic bias in the treatment of patients with obesity. Pointing back to the H1N1 research that was done. eventually somebody looked at it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This notion that people with obesity must be at higher risk because they must be living unhealthy lives, which means that they must have problems of character.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF This notion that if a person has a higher weight, they absolutely have something that they can do about it, that this is something within their control, that this is something that they've chosen for themselves. And that is not the case. There is at least 5000 genes and 37 different hormones involved in weight's regulation. From metabolism to hunger and craving levels to how long it takes a person to feel full or how long they feel full for to the emotional impact food has on things like our bodies’ cortisol levels. And we can't change those genes in hormones, let alone even really test for them right now. And yet people are still comfortable saying, ‘Oh, you're this tall, you're supposed to be this much.’ And this idea that people can intentionally change their behaviors that actually can help with 80, 85% of all chronic non-communicable diseases. But there's only one that we moralize about, and that's obesity.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What happens in the doctor's office then?

DR YONI FREEDHOFF There's two answers. One is judgments. People with obesity are judged or blamed by their health care providers in a way that people without obesity are absolutely not. So that's number one. And number two is that people going into their doctor's offices with obesity who also have pain or a problem with some aspect of their body or their life, they're simply told it's because of your weight. And that does not happen to people who don't have obesity. We know it happens. It is a huge problem that's well researched.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We know there's a decrease in the amount of screening for certain diseases offered to people who have obesity. We know they come into doctor's offices later in large part because of the weight bias they've experienced. And we know that showing up later can really change the outcome of a disease when it's finally diagnosed.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF All of those things are true.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There's been a lot of coverage of the risks of obesity in the pandemic, and you pointed to a CNBC headline that went “CDC study finds about 78% of people hospitalized for COVID were overweight or obese.”

DR YONI FREEDHOFF Well, I mean, that's roughly the percentage of the population who would be described on the basis of their BMI as people with obesity or overweight. So it was a very silly headline. But put in Google News, search the words “obesity'' and “COVID,” and you will find all sorts of ridiculous statements and recommendations. I mean, it's easy to say that we should all be living healthy lives, but it is not clear that if somebody read one of these articles and then took on some means to extremely and rapidly reduce their weights, if being in an active phase of weight loss is a good place to be when facing an infection with COVID.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So this is a question we ask a lot of guests on this show. But if you had advice for the public just about the coverage of weight in general.

DR YONI FREEDHOFF There is a term that I coined in the early 2000's called ‘best weight’ where, rather than talk about BMI tables or numbers on scales. A person's best weight is whatever weight they reach when they're living the healthiest life they actually enjoy. Whatever a person's weight is when they're living the healthiest life they can actually enjoy, that's their best weight. And that's what our goal should be and our best change. So, for instance, our best during a pandemic in a surge is going to be very different, perhaps, than the best life we can live in the before-times. So many things affect our lives and our behaviors so many of which are circled by privilege. We forget that too much. Our job in life is to do the best we can, and that goes for healthy living, for being a parent, for being an employee. The list goes on and on. But we need to stop expecting to be doing better than our best, regardless of what a headline, a scale or a body mass index table tells you. Scales do not measure the presence or absence of health, and they never will.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Dr. Yoni Freedhoff is associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.