BROOKE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.Did you know that last month, Google secured a patent for a cancer fighting device you can wear on your wrist? Quackery? Maybe not. Look it up. You know you want to.)

I only mention it because a study conducted at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics found that news reports were overly optimistic about cancer. Those researchers observed in 2010 that roughly half of US cancer patients die of the disease or related complications. But the majority of the coverage focused solely on aggressive treatments, and only 13 percent reported that those treatments can fail.

Hollywood serves up a vastly different story, as we shall see. But first, some views of movie cancer, as seen from the mezzanine of real life.

NATE: HI my name is Nate, and I'm calling from Greeley, Colorado., My dad passed away a few years ago from non Hodgkin s lymphoma. My main problem with Hollywood's depiction of cancer is how they handle the deathbed. It's always too neat. The person who's dying is like nearly always serene and beneficent, maybe a little pale but never actually looks sick enough to be dying. And never has to go to the bathroom or be laboriously moved around because they can't do it themselves. There's rarely any waiting around or cycles of pain and not pain or fear and not fear. And I don't know, it seems like for most people, the death bed is probably more David Lynch than Steven Spielberg.

BROOKE: One thing is clear. Cancer on the silver screen is very different from real life, or the news media. Hollywood cancer is almost always fatal. But no, it’s all good.

EAGAN: ...cancer could be seen as a way to force people to examine relationships that they didn't want to examine, it could be a way for them to confront their own mortality, it could be a way to remove a character so that other relationships could develop.

BROOKE: Daniel Eagan is author of "America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry." He says Hollywood usually depicts disease as a challenge to be overcome. But not cancer.

EAGAN: Especially in the early years of Hollywood, there was no cure...so there was no way to find a way to live with it because basically you were going to die.

BROOKE: So what cancer offered screenwriters was an easy way to engineer the personal growth of their characters. The dying get to grow - briefly. But the living, well they can draw on that ennobling grief forever, as in A Walk to Remember.

CLIP:

SHANE WEST: Janie saved my life. She taught me everything about life, hope, and the long journey ahead.

EAGAN: ...the way Hollywood used it, it was a very clean disease, a very clean way to die. It wasn't like leprosy or dysentery. It was usually some sort of inoperable tumor that was never seen and then you just...quietly faded away.

BROOKE: Especially, it seems, brain cancer.

EAGAN: Yes, brain cancer is a favorite.

BROOKE: One of the earliest films with cancer, yes, brain cancer, was released in 1939…

CLIP:

We’re off to see the wizard, the wonderful wizard of oz (fade under)…

BROOKE: No, that was a brain injury… Right. Dark Victory with Bette Davis...

CLIP: DARK VICTORY CLIP

Ann: What’s she got?

Judith: Yes, what have I got?

Dr. Steele: Technically it’s called Glioma.

Judith: Glioma?…

Ann: Oh, don’t listen to him!

Judith: It sounds like a kind of a plant!

Ann: All surgeons are alike, Judy! Dont be upset darling we can call another doctor.

Judith: Yes. Yes of course.

Dr. Steele: But you have to face it sooner or later.

Judith: Suppose we just don’t talk about it anymore!

BROOKE: So, we hear all about "glioma" but the word "cancer" is actually never uttered.

EAGAN: I don't believe they actually used the word until, in Hollywood, until much later--about ten years later.

DARK VICTORY CLIP:

Housekeeper: Another headache Ms. Judith?

Judith: No! Not another headache! Yes! A big headache! And I’ll have a bottle of

champagne for it.

EAGAN: You know it's not really about Bette Davis's cancer, though. It's about how she responds to her death sentence. First, through hedonism. Then through detaching herself from her selfishness. She is dying a better person than she was before.

Jumping to 1970, its the snobby Ryan O’neill that becomes a better person confronting Ali Macgraw’s death. in the blockbuster weepie, Love story.

CLIP:

O’NEILL Jenny I’m Sorry. Love means never having to say you’re sorry

JENNY: Don’t. Love means never having to say you’re sorry.

BROOKE: Roger Ebert, noting the tendency of cinema cancer patients to grow more beautiful as they sicken, dubbed it “Ali Mcgraw’s disease.”

Jumping ahead to 1983, the mother of all tearjerkers, Terms of Endearment, which uses Debra Winger’s cancer to strengthen the bond with her mother, Shirley MacLaine. This is actually a scene with which many real-life families identity.

CLIP:

Aurora: It’s after ten! I see know why she has to have this pain.

Other nurse: Ma’am it’s not my patient.

Aurora: It’s time for her shot. You understand? Do something! All she has to do it hold on till ten! And it’s past ten. My daughter is in pain, get my daughter the shot! Do you understand?! GIVE MY DAUGHTER THE SHOT.

Aurora (takes a breath): thank you very much. Thank you.

BROOKE: Oncologist Giovanni Rosti checked all the movies featuring cancer from 1939 from 2012, and discovered that the victims were usually young, and female, who succumbed to tidy cancers in the brain, as we heard, or the blood.

Of course there are a few exceptions to Hollywood’s use of cancer merely as a device to examine relationships, or reorder priorities in the face of mortality. Sometimes it is really about Cancer.The broadway show and TV movie Wit comes to mind. But mostly, not.

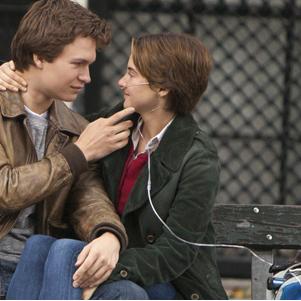

Still, the form has evolved. For instance, the victim in last year’sThe Fault is in our Stars was (spoiler alert!) a young man, and he has bone cancer. In this scene we hear a eulogy he wrote for his also sick, but surviving, beloved...

CLIP:

You don’t get to choose if you get hurt in this world. But you do have a say in who hurts you. And I like my choices. I hope she likes hers. Okay, Hazel Grace?

MESLOW:You know, my feelings about "The Fault In Our Stars" are complicated--both before seeing it and after seeing it.

BROOKE: Scott Meslow is The Week’s film and TV critic. He has mixed feelings about last year’s “The Fault is in Our Stars” because his brother died of the same kind of cancer as the boy in the movie, but...

MESLOW: it does not shy away from the ugliness of cancer. She has a line late in the movie where she says, "I wish I could say he was brave and tough right up to the end but he wasn't." And that's an important acknowledgement for a movie to make. But it's still the kind of movie that was marketed for and made for teenage girls. And so it's going to--

BROOKE: And "50/50" wasn't?r

SCOTT: No. Shockingly, that was a different audience.

BROOKE: [Laughs] Teenage boys?

SCOTT: Yeah. [Laughter]

BROOKE: Meslow loves 50-50, the sole cancer comedy we could find. The script was based on the writer Will Reiser’s story, he was diagnosed with cancer in the spine, with a 50-50 chance of survival. His character is played by Joseph Gordon Levitt, and co-stars his real-life friend Seth Rogan. It was critically acclaimed. In part, because the hero is not a perfect pearl. He’s a mess. He even listens to Rogan’s advice to leverage his cancer to get girls.

CLIP:

Kyle: You know what I’d do? Get into the cancer thing faster.

Adam: Faster??

Kyle: Faster! Its your hook, man! It’s what you got!

Adam: So what...thats like the first thing I say?

Kyle: Thats what makes you different. Thats what sets you apart.

Adam: Ok ok! (Adam approaches a girl)

Adam: Its a great song! \

Girl: Totally.

Adam: I have cancer…

Kyle: I was wrong! I was wrong. It was weird like that.

BROOKE: Why do you think we haven't seen more cancer comedies?

SCOTT: Well, I think it starts with calling it a "cancer comedy." It doesn't sound like a very compatible idea. If you're a screenwriter you might look at that mountain and say, "I can't climb that."

BROOKE: Kind of like "Springtime for Hitler?"

SCOTT: Yeah! [Laughter] You can't possibly in theory combine those two ideas. I think, "50/50" proved that it can be done, but that was a very specific treatment from someone with a very specific experience who basically had the chops to say, "Look, there are funny things about having cancer." Certainly, when it came down to my brother we laughed all the time. You know, we had a lot of fun. It wasn't like it was the only thing we ever talked about or did.

BROOKE: Specificity, a basic rule of drama: a specific person, a specific constellation of relationships, a specific cancer. That’s what makes makes it real, even if he gets does wind up with the girl. Because, we know know cancer is complicated, like the people it afflicts. And as we age, we see it more. Which is why I’m guessing Hollywood’s old cardboard cancers may soon outlive their usefulness, or at the very least, be played increasingly for laughs.

Coming up, owning cancer: how people seize or shun technology to control their own stories, and sometimes, change the lives of strangers.

JARVIS: Hi OTM, it's Jeff Jarvis. Feel free to use my whole name. I've had prostate cancer and thyroid cancer, and I've written about both online. Thus I've told the entire world about my malfunctioning penis. You might wonder if I'm insane, but I've actually found great value in this. I got support, I got information. I inspired other people to get tested. I'm lucky, I had cancer light. Nonetheless, I found my path much easier because I shared it.

BROOKE: This is On the Media.