BOB GARFIELD: Among the many parties pushing for the confirmation of Judge Brett Kavanaugh is the Judicial Crisis Network, a political nonprofit committed to, as it says on its website, “strengthening liberty and justice in America.” As recently as this week, that took the form of ads meant to drum up support for Judge Kavanaugh.

[CLIP]:

SPOKESWOMAN: With no valid reason to block Kavanaugh, Democrats started a smear campaign, disgusting accusations, unproven, discredited. Kavanaugh denies them…

[END CLIP]

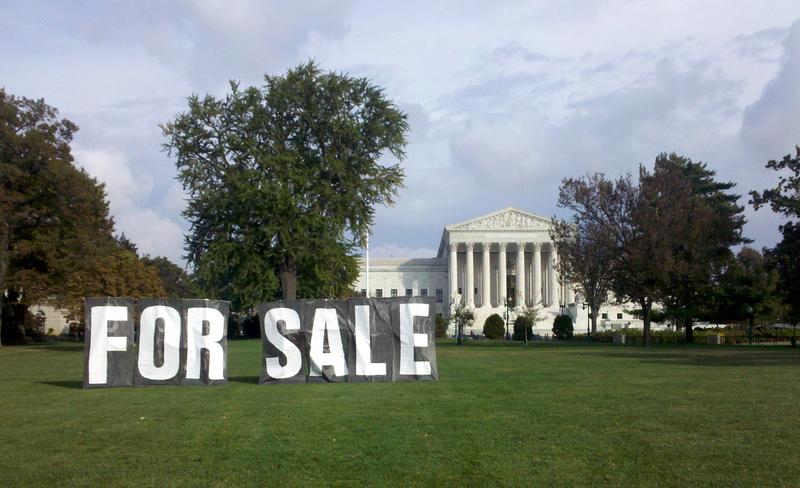

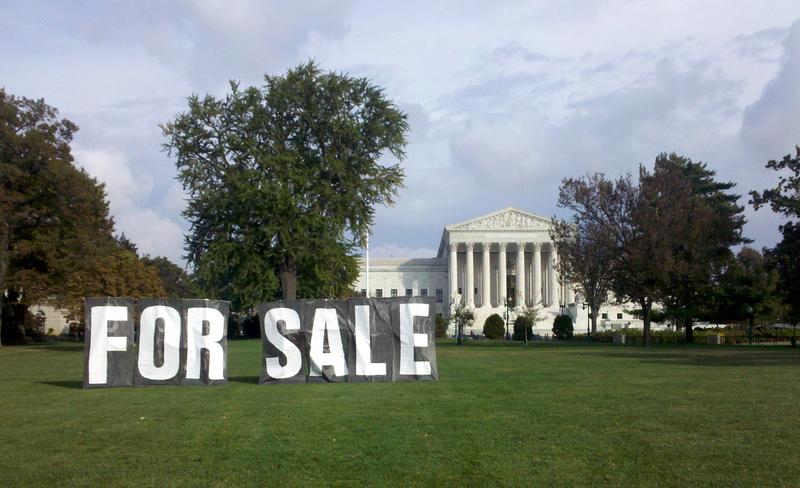

BOB GARFIELD: Now, if you or some enterprising political reporter were interested in the Judicial Crisis Network’s funding sources, you'd be out of luck. The JCN is a 501(c)(4) in the eyes of the IRS, a so-called “social welfare group” that is not obligated to disclose its donors, so long as its primary spending is non-political, that is, until the Supreme Court earlier this month let stand a lower court ruling that has the potential to throw open the shades and compel dark money groups to accept a more transparent status quo, maybe. Michelle Ye Hee Lee is a national reporter covering money and influence in politics for the Washington Post. Michelle, welcome to OTM.

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: When the Supreme Court declined to review the case earlier this month, it seemed like that might transform the nature of dark money politics. For anyone with an interest in transparency, what was the most optimistic series of events that could flow from that lower court ruling?

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: If you're someone who is interested in the identities of the donors who have been giving to the dark money groups, the rosiest scenario that could happen here is that the groups start disclosing many of their donors who you had not heard of before as early as October 15th, which is the next quarterly deadline for these groups to file their documents with the Federal Election Commission. That would be quite monumental.

BOB GARFIELD: But then reality rears its head. A new disclosure environment would require two federal agencies, the FEC and the IRS, to promulgate new rules and to adopt them but there, Michelle, we run into political and bureaucratic dysfunction. Tell me how.

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: The Federal Election Commission right now barely has a quorum. It’s supposed to have six commissioners to vote on matters, to decide whether to enforce the law, enforce regulations, hold groups accountable as they run afoul of the law or regulations, but the FEC right now only had four commissioners, which is the bare minimum vote you need in order to do anything. And the four commissioners are split along ideological lines. Two of them are Republicans, two of them are Democrats. So it’s very difficult for work to get done there, and this has been the case for a while now.

The FEC now needs to come up with a brand new regulation, which takes months to write, and then it has to go up for a public comment period, which is probably another month or two, and then it has to come before Congress for at least a month. So there is a long way to go until some clear guidelines are given.

On the other side, the IRS has really chosen to protect the donors’ identities rather than to disclose their identities, and this is the way the IRS has been moving recently because they believe that there is too much room for error, that there had been leaks of donors who did not want to be disclosed. So the IRS has moved away from disclosure. So it’s really unlikely that these government agencies are going to do anything in time to make a huge difference for the midterms, certainly, or even in time to make a real difference next year.

BOB GARFIELD: And let's just say, in some fantasy world, both the Federal Election Commission and the IRS do pass some explicit rules governing 501(c)(4)s and a similar category, 501(c)(6)s, if we know anything from history, it's that political money adapts. If you’re a political high roller and rules change, you know, you’re going to find a new way to donate. If you ran the Michelle Ye Hee Lee Political Action Committee, what would be your next move?

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: So if I was the Michelle Ye Hee Lee social welfare nonprofit, I as a nonprofit could say to a donor, could you give me some money to help flip the Senate and then I will use your money in whatever way it takes to get there? So these groups are now changing the way that they're asking donors for money. They might be asking to generally support what I support as a group, please give us money, and then maybe they'll try to use the money for a political purpose. It’s very unclear if that’s allowed, but that's one creative way that the groups might start doing at.

Another way that the groups may start operating is that we might give [ ? ] to a Super PAC, so I as the Michelle Ye Hee Lee nonprofit group take the donation and then I make a donation to a Super PAC instead. That way the Super PAC only discloses the nonprofit that gave the money, the Michelle Ye Hee Lee nonprofit, and would not have to disclose any of the donors who gave the money to the nonprofit. So essentially, it’s adding one more layer between the identity of the donor and whatever will trigger the disclosure of that person's identity.

BOB GARFIELD: Also known as money laundering.

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: That is what some critics might call it. I wouldn’t, as an objective reporter, call it that.

BOB GARFIELD: If there is a change in the, the political donor ecosystem, at what point do you think the status quo will change, by the 2020 presidential election, for example?

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: Although it's not officially in effect and we may not see any sort of official change in behavior for the midterm, it’s already started altering behavior of donors and Super PACs and nonprofits. The groups that I’ve spoken with, the donors that I’ve spoken with have been aware of a possible change coming down the pike. And when the lower court ruling came down in early August, it actually put a lot of these groups on alert. So they have been scrambling to figure out with their legal counsel what this means for their fundraising for 2018, what they should be telling their donors, how they should change the script for asking for donations. And donors are already asking, well, what does this mean for me? How early could my identity be disclosed to the public? And it’s actually changed a lot of behaviors already.

BOB GARFIELD: Let me ask you one last thing. However this plays out, it still seems to me like a surprising decision by a Roberts court, a Citizens United court, to let stand this lower court decision that complicated life for political donors. Can we divine anything about this situation, beyond its particulars?

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: There is very little we could read into the way that the Supreme Court reacted here because we don't know why that happened. We don't know whether that’s because the other justices deadlocked 4-4 on this or whether they just wanted it to go through the full appeals process. We just have no idea.

What is interesting about this, certainly in the context of Judge Kavanaugh’s nomination, is that after this case goes through appeal, it could come back before the Supreme Court. And if there is a Justice Kavanaugh who is not a fan of donor disclosure or campaign finance regulation, it could really make a huge impact in the way campaign finance regulations are decided on at the Supreme Court level. So it has very interesting implications there just looking forward.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Michelle, thank you so much.

MICHELLE YE HEE LEE: Thank you so much.

BOB GARFIELD: Michalle Ye Hee Lee is a national reporter for the Washington Post.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, your moment of much needed Zen.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.