BROOKE: From WNYC in New York this is On the Media, Bob Garfield is away, I’m Brooke Gladstone, devoting this episode to perceptions of cancer, in language, in the news, in our mind’s eye. So quick, what do you see, when I say the word cancer? A bald head? An x-ray? A loved one?

What I see is a pulsating cell, fiery red, with sunken eyes, a sinister grin, and radiating spikes that twitch and stretch and scrabble across my field of vision. Seriously, that’s what I see. In this edition of the show, and next week’s, we’re drilling deep down into the construction of cancer, as metaphor, entertainment and crucible for public action. For it has been, always will be, too much with us, as long as we live, the longer we live.

Siddhartha Mukherjee: The way that cancer has insinuated itself into public imagination has a long history, and that’s why I think it was exciting, to you know imagine what the life of cancer was like.

We’re launching this hour with Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Emperor of all Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. He says our notion of cancer’s fierce and adamant nature begins with its name.

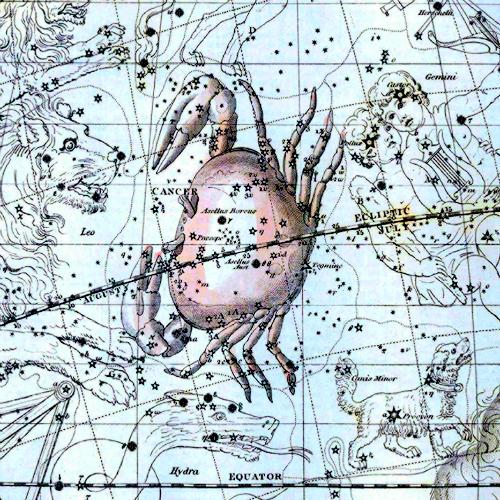

Mukherjee: It comes to us from ancient times. The word refers to the word crab. For a reason that’s very visceral. The ancient physicians, the legend goes that even Hippocrates, thought that a lump of cancer was like a crab buried under the sand and all the inflamed blood vessels around it were like the legs of the crab. And then it just got more and more enriched. People thought the pincers of the crab was the sideways movement of cancer metastases.

Brooke: The oldest reference that you know of comes from ancient Egypt.

Mukherjee: In fact the oldest reference is probably the oldest medical documents we posses as humans. In fact the very very oldest document, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, its a surprisingly modern document, even though it was written around 2,500 BC, which has case histories, and one of those case histories seems like a case of breast cancer. We can't be sure.

Brooke: Sounds like it though, doesn't it.

Mukherjee: Yeah its an incredibly vivid description. It says "a mass in the breast, as dense and hard as a hemat fruit" a kind of fruit that you can find in that part of the world, and its "cool to the touch." As opposed to the inflammatory puss forming in infectious causes. Every case in the papyrus - its very organized, it has a case description, a therapy, and a prognosis - and perhaps the most moving thing about the description is that in treatment and prognosis the scribes wrote, "There is none."

Brooke: I thought it was really interesting, though, as you described the history - it seems to vanish, any mention of cancer, for a couple of thousand years. Why do you think the record goes silent?

Mukherjee: Well the main reason is that cancer is an age related disease. Not all cancers, obviously, there are cancers of childhood, but its mainly an age related disease and people just didn't live long enough. So there wasn't much cancer in the ancient world. And when it did occur in the ancient world, it was viewed as a kind of catastrophe, a visitation from destiny or fate.

Brooke: Queen Atossa, of Persia, was not an old woman.

Mukherjee: Queen Atossa's story is a very moving story. She is diagnosed with what seems like breast cancer. And her response is surprisingly contemporary. Her first response is shame. She is really haunted by the stigma of this thing that's growing in her breast. We are told from Herodotus, she wraps herself in sheets and sort of vanishes, until a greek slave is asked to remove the tumor.

Brooke: Is he asked, or does he offer?

Mukherjee: He may have offered - he clearly is versed in the arts of surgery. And there's an interesting trade that he makes. He asks the Queen to ask her husband--

Brooke: Who by the way is Darius the Great.

Mukherjee: No less than Darius the Great, who rules what was then one of the most powerful kingdoms in the world. The slave, Democedies is his name, asks the king to turn the campaign away from the Persian front toward the Greek front so that the Greek can return to his own homeland, now conquered by the king. And he, the slave, as far as we know, successfully delivers this operation, and in fact the king does turn his campaign and that launches the Greco-Persian wars which, in turn, launches the early history of the modern west. You can suddenly see that so much of history turns on biography. So much of history turns on the biography of illness. In this case, of breast cancer.

Brooke: However ancient the roots of cancer, it is perceived as essentially a modern disease and this has everything to do with metaphor.

Mukherjee: In metaphor, its described as a disease of excess. Its probably interesting to counterpoise it with the other disease that really occupied public imagination in the 19th century, which was tuberculosis. You know, tuberculosis was called consumption, and it was a hollowing out, it would eat you up from within. There was a romantic, Victorian idea of fading away.

Brooke: Beautifully...

Mukherjee: It was a beautiful death. You know, Byron famously romanticized it. And cancer was quite the opposite. It was a death in which lumps grew out of nowhere. It wasn't a beautiful death - it was a death by choking, by excess.

Brooke: Being filled up with --

Mukherjee: Malignant cells. The observation was that masses - things that shouldn't be there - were suddenly boiling up or bubbling up. Self control had somehow become disregulated and begun to metamorphose. And so the idea was that cancer was the body in excess.

Brooke: How is that modern?

Mukherjee: There was very much in Victorian times the idea that modernity was excess, that capitalism was excess. Filling up with exaggerations of money, of desire.

Brooke: And then on top of that, this idea of metastasis. A disease always in motion, like modernity.

Mukherjee: Exactly. Even the word metastasis. Meta - stasis. Suggests the notion that it is beyond stasis. Movement - constant movement. In this case, the ill-defined and ugly movement which ultimately causes death.

Brooke: You wrote "this image of cancer as our desperate, malevolent, contemporary doppleganger is so haunting because it is at least partly true."

Mukherjee: Because the cells that cause cancer are cells in your own body. And this also haunted post-Victorian imagination. Because most of the disease that we knew were microbial. They came from outside. And then all of a sudden we began to discover diseases where the pathology was from inside, from yourself. Why is it that a perfectly normal cell living a perfectly normal good citizen life, woke up one day and became a cell in excess. Why is it marauding other parts of the body and colonizing them.

Brooke: You describe doctors throughout the last century and even in the beginning of this century as like a pack of blind people touching the different parts of the proverbial elephant. Each declaring that they have the whole picture.

Mukherjee: It was quite clear from the 19th century pathologists that cancer was ultimately caused by cells dividing when they shouldn't be dividing. But what caused that? It turns out that on occasion, a virus, a foreign microbe can cause that kind of dis-regulated cell division. So immediately scientists thought they've got all the answers. This is a typical kind of progression in which you find one instance and you generalize it to all instances. And therefore by the 1940s it was clear that cancer must be a viral disease. And of course viral diseases are sometimes curable. So this was a lovely idea, it was all perfect. The media picked it up as a contagious disease and I describe this moment of wonder and delight that cancers would all be solved. Just like other viral diseases can be vaccinated, maybe you could vaccinate against all cancer. Now notice, we're still referring to cancer as one big C, one kind of virus, and that's because people thought that despite there being so many different kinds of cancer, all cancers would have a common cause.

Brooke: The unified theory of cancer was like trying to reconcile Newtonian quantum physics.

Mukherjee: That's right. There was a quest - and this quest still remains with us - to find a grand unified theory of cancer. And the early virus hunters had gotten a clue because they could put viruses into chickens and create cancers that looked like real cancers. But then there were things that didn’t fit that clue. For instance why did chimney sweeps in england get cancer of the scrotum? They weren’t being affected by viruses. Why did people who smoked die of lung cancer? That didn’t fit. Why did people like, famously, Marie Curie, die of a precancerous lesion, exposure to radium… Why were all these people dying if cancer was a virus? And then the third thing that didn’t fit - was that there were clearly hereditary forms of cancer. Breast cancer clearly ran in families. Why was it in families? Was it being caused by environmental effects? Was it a virus? There was a triangle of forces trying to find a grand unifying theory of cancer. Like three blind men trying to touch the elephant.

Brooke: Siddhartha Mukherjee is author of The Emperor of All Maladies. Coming up, the stories we tell ourselves about cancer.

Abigail (listener): Hi, my name is Abigail, calling from Atlanta, Georgia. My mother died of lung cancer. The things that really make me cringe is this idea that if you have a positive attitude you will survive and you will beat cancer. My mother had a great attitude and she worked really hard to beat cancer. I think my mother felt, towards the end, that transitioning to hospice care and palliative care and a comfort approach, which I think really would have benefited her, also was kind of quitting and therefore not fighting hard enough.

Brooke: This is On the Media.