Breaking News Consumer's Handbook: Vaccine Edition

( David Zalubowski / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

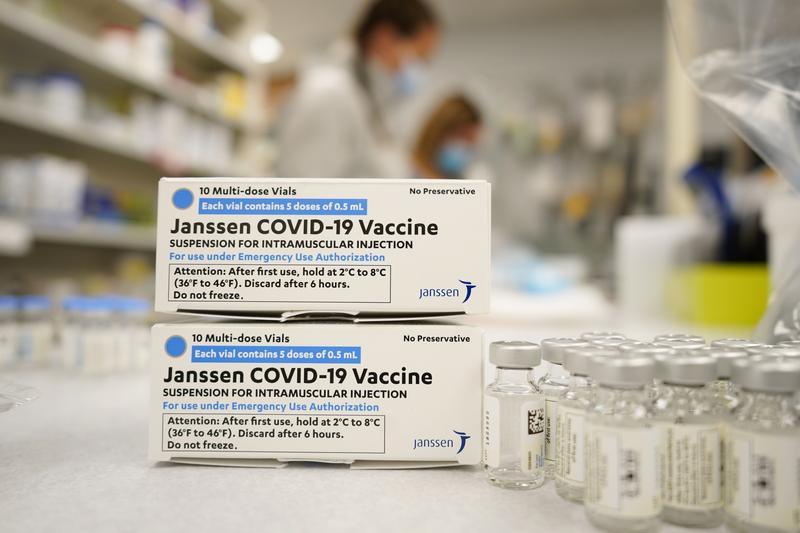

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. This past Wednesday, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, a special panel within the CDC, met for an emergency. The problem: Johnson and Johnson's coronavirus vaccine.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The CDC and FDA just released a joint statement that is calling for an immediate pause in the use of the Johnson and Johnson single dose coronavirus vaccines. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT This vaccine has already been given to 6.8 million Americans, and now investigators are looking into 6 cases of blood clots, all in women, all under the age of 48 who received that vaccine. [END CLIP].

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Johnson and Johnson now says it'll delay the rollout of the vaccine in Europe. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Was Johnson and Johnson causing these blood clots, or just in the biologically wrong place at the wrong time. If the vaccines did cause the clots? What's the risk to everyone else? Should all of the nearly 7 million recipients of the one-shot wonder be concerned? And then, thorniest of all, the logistics. Pausing production of any vaccine in a pandemic is not a simple calculation.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Any extension of the pause will result in the fact that the most vulnerable individuals, in the United States, will remain vulnerable. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE On this point, there was true debate not just on the panel, not just in the virtual world of Twitter hot takes, but in the world of flesh and bone. Would putting Johnson and Johnson on ice inspire trust in our health systems, or play to the skeptics or the vaccine hesitant? We don't know, and neither does the CDC. Thoughtfully and anticlimactically, the panel punted, deciding not to decide on J and J's fate without more data, because that's what scientists do. Perhaps you wondered, well, what does that mean? How bad is this? So, while we all sit in the great waiting room of science together, we bring you the latest in our series of Breaking News Consumer Handbooks: Vaccine Edition. What the Johnson and Johnson episode exposes, among other things, is our long and paradoxical relationship with vaccines that asks us to invite foreign bodies into our own bodies. There's always a chance that things don't go perfectly. There are side effects, and the other hot button word of the week – breakthrough infections – but the headlines usually emphasize just the top half of a simple fraction to represent the whole, which inevitably yields the wrong answer.

NSIKAN AKPAN We really need to know what the denominator is in order to tell people how big the risk is.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Nsikan Akpan is the health and science editor for the WNYC NEWSROOM. He wrote a piece this week for The Gothamist on the wave of breakthrough infection stories hitting the news.

NSIKAN AKPAN Think back to your middle school math class, and when you're doing fractions. The numerator is the number of top, the denominator is the number in the bottom, and I can tell you percentages or what proportion of people might be involved with a certain situation

BROOKE GLADSTONE When it comes to breakthrough infections, that percentage, it turns out, is very, very low. And that's point 1 in our handbook. Just because the story is everywhere doesn't mean the risks are. Point 2 is to note that the scary headlines tend to focus on the numerator and leave out the contextualizing denominator. One big story recently was about breakthrough infections in Michigan, 246 of them out of a million and a half who got the vaccine. So do the math, 246 out of a million and a half is about one in 10000. So what does that tell us?

NSIKAN AKPAN Everyone has likely heard this 95 percent number with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Do that math for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. You would predict that about one in 2000 people who get vaccinated with those vaccines would experience a breakthrough infection.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That is using the 90 to 95 percent efficacy number, right?

NSIKAN AKPAN Exactly. So you have one in two thousand there. You set up the Michigan numbers, 246 breakthrough infections, over 1.5 million vaccinated from the beginning of the year to the end of March. That gives you 1 in 10000.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's a lot better than one in 2000.

NSIKAN AKPAN Right. What the numbers from Michigan are telling us is that the vaccines appear to be doing better than expected based off of the clinical trial results.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Pretty surprising. That said, we can't just blame the headlines. Beneath them lie a complicated vocabulary of terms that may mean one thing to researchers and something entirely else to the rest of us. Point 3, learn the vaccine lexicon. Pause, for instance, may not mean what you think it means. Kai Kupferschmidt is a science journalist based in Berlin who writes for Science magazine.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT Clinical trials with covid-19 were done in 20, 30, 40000 people. If you have a side effect that only occurs, say, once in 100000 people, then you're not going to pick that up before you actually start giving the vaccine to millions of people. This is something that we've seen with many vaccines that you start rolling it out, you see a safety signal. In the beginning, it's hard to know whether this is really something that the vaccine is causing or whether this is just basically a coincidence. And so it's investigated, and normally what you do is you pause using the vaccine while you investigate the safety signal. And then, you know, depending on what you find, you might restarted or stop it or restarted just in some people, of course. What's different this time is that we're doing all of this in the middle of a devastating pandemic that has killed more than three million people. So, the stakes are that much higher.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Science expects these moments and so should we. Breakthrough just means an infection that has made it past the vaccinated person's defenses. Breakthrough does not mean the vaccine no longer works. In inoculating hundreds of millions of people, there will be side effects, infections and deaths, but so much less death. And if you think back to the halcyon days of yore, we know this, we act on this knowledge every single year. Which is point 4, every virus mutates, not necessarily for the worse. We vaccinate annually against the descendants of the horrific 1918 flu. Every year, the offspring of a virus older than Jay Gatsby causes breakthrough infections across the world, but we don't see it that way. We see it as a dinner party anecdote. "You know, I got my flu shot and I still caught it." We don't see ourselves in a headline saying millions saved by vaccines again. But of course, maybe the issue isn't the headlines or the language or even the virus, maybe it's the vaccine itself that's causing this communication problem. That's point 5. Civilization's greatest invention, I think, is the vaccine. But the concept is abstractly terrifying. It just feels risky.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT It's worth remembering that humans are very bad at judging rare risks, right. At the moment, this is such a rare event, there was one comparison, I haven't actually checked the numbers, but that you're more likely to have a car accident on the way to being vaccinated than, you know, having the side effect from the vaccination.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank God for cars! We're always more likely to get into trouble there than almost anything else!

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT Exactly that that always helps as a comparison. But I also think that some of these comparisons aren't very helpful, because you do have to remember, you know, the psychology of vaccination is quite complicated. I mean, we are talking about something that you give to healthy people. Most people find the idea of something being injected into the body in itself kind of scary.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You said that we calculate our own risk on the basis of whether or not we are currently well, in part because if we are currently well, maybe we can take measures to ensure we stay well, you know, double mask and all the stuff they tell us to do.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT I think there are several things that trip us up when we do these risk calculations. One of them is that as humans, we have this illusion of control. So if somebody injects something in your body, you feel that you have no control over whether you're going to have the side effect or not. When you're driving a car, of course, you know, your control over whether you're going to get in an accident is also very small. You can easily get in an accident even though you do everything right, but we have this idea that we are in control of that risk. The other thing is that we tend towards risks of omission rather than commission. So if you ask, for instance, a mother whether she would vaccinate her child and you tell her, well, there's the same risk for the child getting this rare disease if you don't vaccinate him. But then there's the risk. If you vaccinate him, people tend to choose the risk, which is not their fault. You know, in quotation marks, it's the feeling of, well, if it happens, it happens, but I didn't do it. So there's all of these different factors that play a role psychologically when we're judging these risks, and I think sometimes it just helps to explain these factors, like especially in this pandemic, it's almost become the overriding thing is to try and understand your biases in how we aggregate this data and perceive it and what our ultimate conclusions are.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Not so easy. Tracking how our brain works, it's like trying to see air.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT And this is something that in the debate about this Johnson and Johnson pause that really upset me was just the way that everybody, you know, 2 minutes after that pause was announced that everybody was so sure that this was either a complete disaster and the wrong decision or clearly this was right and the vaccine should be immediately taken off the market. Now, these things are quite complicated, and it is worth taking the time to understand all the factors that play a role in this decision making.

BROOKE GLADSTONE A crucial factor in the decision to pause the J&J vaccine was not just about clots, but a particular kind of clot combined with a reduction in platelets. Something requiring study. Digging into these factors enable us to get a grip on risky feelings floating like vapor in the air. You may be inclined to see disaster for yourself in a headline, but the truth is you have a very personalized risk equation. Point 6, scrutinize how you assess risk. When facing patchwork vaccine news, it's vital to know thyself.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT 6 cases. That's what we have at the moment. 6 cases in more than 7 million people vaccinated with this in the US, isn't a lot right. But you have to realize that it takes some time to see these blood clots and for people to be diagnosed for it to be reported. Now, the ACIP meeting, the body that decides on these recommendations, which is the body of CDC and FDA, this was on Wednesday evening. In their deliberations, they made it very clear that they would expect that any cases from the first, say, 3.5 million people vaccinated might have been reported now, but the 3.5 million people that were vaccinated with Johnson & Johnson in the past 2 weeks, we probably haven't seen those cases yet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So assessments are underway to determine who and how many, out of millions, face a risk, however rare. It's a pause, but as he noted, many had already made up their minds. Critics of the pause on social media were quick to compare the risk of the clots experienced by the 6 women with the risk of clots of a different kind associated with birth control pills. The risk of those clots is much bigger, though still very small. So why all the fuss? Point 7, analogies dramatically understate the complexity of the data. Risk assessments also obviously govern our behavior, despite the better than predicted response to the vaccine in Michigan, case rates are soaring. Why? Well, the vaccine rollout hasn't gone so well, but perhaps more important are those personal risk assessments. Nsikan Akpan.

NSIKAN AKPAN There has been what I would describe as a libertarian spirit through much of Michigan's pandemic response. So, you have to think, OK, people are mingling, right? They're getting exposed, and one of the biggest factors, whether or not you catch any germ, is your exposure. And that also applies to vaccinated people. You know, there was this caveat in the CDC's travel policy that came out a few weeks ago that said, OK, people are vaccinated. You still need to wear a mask in transit. That's because you're going to be interacting with crowds. You don't know if those people are vaccinated and are protected. There is the chance that you could get exposed to a large volume of the virus. And then even in that situation, your immunity might break down and you might get infected. You know, your immune system is a bit like the deflector shields in Star Wars or Star Trek. You hit your immune system or your immunity with a short laser beam, a virus [mimic's the PEW of a blaster gun]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The shields hold, but if you're hammered by a ship that is cloaked...

[BOTH LAUGH]

NSIKAN AKPAN Yeah, if Darth Vader is bearing down on you with an imperial class destroyer. Sorry, I'm getting way too nerdy here – your shields are going to have a harder time. So, there is going to be a higher chance that you might catch that virus and that could happen to people who are vaccinated too.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Point 8: effectiveness in a lab and in the real world are two different numbers. Real world numbers come later. They may actually be better. The CDC just announced that 5800 vaccinated people experienced breakthrough infections so far. 77 million Americans have been fully vaccinated. Do the math. But the story isn't over with science. It never is. In the murky early days of the breakout, we were wiping down our groceries, unsure how it spread, now we know better. The virus is still with us, and even vaccinated we're not invulnerable, but new information can guide us if we're flexible. If we see knowledge as a process, as scientists do.

NSIKAN AKPAN An essential part of science reporting is saying, here's what we know, here's what we don't know, and here's why it doesn't mean the sky is falling. I still see people on the street hop down from sidewalks whenever a jogger runs by them. What we know about airborne coronavirus is that the risk is extremely low outdoors, especially when you're spending a short time next to somebody. You know, the odds of that jogger being able to give you coronavirus is next to none. Yet there was so much reporting about airborne coronavirus last summer, people really got it in their heads that the outdoors is a dangerous place. And the lack of context there at the very beginning can have really serious ramifications down the line.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now, there's a lot of evidence suggesting the outdoors are pretty safe, but those initial headlines tweaked your behavior and your reactions to the behaviors of others months ago. Meanwhile, news happens and some of it changes things, but some of it is not quite ready for consumption. We'll consume it anyway. Point 9, studies are not created equal. Find a voice to help you through the weeds or just walk away.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT And I think we have basically systematically miseducated our readers about how science works because we never describe the process all that well and because we keep writing stories that basically say new research shows that 3 cups of coffee a day reduces your risk of Alzheimer's or increases your risk of cancer. You know, I'm not really interested in this one study. I'm really curious to know, what about the 50 studies that have been done about the same issue before? What does the balance of the evidence say? Because you might get a really well-done clinical trial that basically answers the question really well. And then 3 weeks later, another result comes out, that's different, but it's from a clinical trial that was much smaller, that wasn't as well done, but, of course, that's the news. So we have this implicit bias in journalism towards what's new and not what's true, and I think that's a really hard one to break through.

BROOKE GLADSTONE If there's something the news and science have in common is that both are getting faster. Be patient with yourself, working through the numbers, the risks, the benefits is hard. Remember, this is new territory for scientists, and journalists too.

KAI KUPFERSCHMIDT We would serve our readers a lot better if we would write stories that aren't really about results that are about the process. I think in some ways the meeting on Wednesday evening was really interesting because they didn't come up with any decision in the end, you know, they didn't unpause the vaccine or anything, but the process was fascinating to watch. Some of the greatest novels or movies, you know, kind of have an open ending. If you can manage to tell a really, really interesting story, then, you know, then you've got your reader listening to you. And maybe at the end, the fact that there is no result, yet, isn't as important. But of course, that's a hard sell to editors – I know that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We conclude on point 10: Be flexible. Science is a process that never ends. As the data flow in, the advice will change. Meanwhile, what can I get you? One mask or two? Sanitizer anyone? Or is there a gallon of it at home crying for your attention because, you know, your overbought. This isn't going to last forever, but something else is bound to come up, so don't do it halfway. Either pay really close attention to vaccine news, or not much at all. If you're vaccinated, you've already got it covered the best you can.

BOB GARFIELD Coming up, the blowout in Bessemer and the lessons it holds for organizers and the media.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.