BROOKE: Now another instance of correcting the historical record: this time in the form of an apology. Back in 2006, The Charlotte Observer and Raleigh’s News & Observer apologized in separate editorials for their part in a little known chapter of American history: In North Carolina 116 years ago a biracial coalition of Republicans and populists had for some years controlled two Senate seats, the governorship and a legislative majority. Supporters of the so called "fusion movement" were mostly white, but in some counties, black men held elective office, too. All that came to a bloody end one November night in what’s known as the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898. Spurred on by the local press, white mobs set fire to black-owned businesses and overthrew the city's fusion government. They killed dozens of blacks and ran thousands out of town.

BOB: Finally, in the year 2000, a state commission was created to investigate the episode. The commission concluded that the horror in Wilmington was not so much a riot as an insurrection, a coup d'etat orchestrated by prominent members of the Democratic Party. They wanted to topple the fusion government. And though they had big business on their side, as well as a number of regional papers, that wasn't enough. They needed the poor white farmers. And so, as Duke professor Timothy Tyson told us a few years back, the Democrats used the printing press to paint the conflict in black and white.

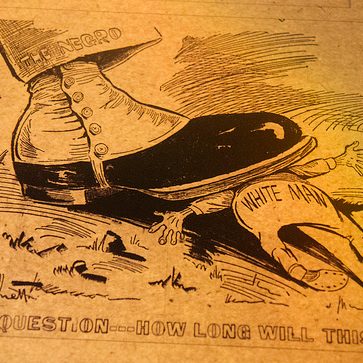

TIMOTHY TYSON: So they put this red hot, scurrilous, very sort of sexually oriented, near pornographic material out in the newspapers about the sort of black beast, black brutes, especially in the counties that had heavy black majorities. What you had to do was to shame white men who had voted with black men and say that they had failed to protect their womenfolk. They tried to shame white men into voting race, instead of sticking with their economic interests.

BOB: Can you give me some specific examples of headlines or articles or cartoons that were inciting violence and racial hatred?

TYSON: Well, for example, there's a cartoon of a big, black vampire-like thing with wings -- "the incubus of Negro domination" -- you know, carrying off white women in its claws. And The News and Observer would run a cartoon of a white woman taken before a black magistrate, for example, and the black magistrate, you know, being licentious, as if, you know--oh where, you know, you're in trouble, are you? -- and then acting as though they would be sexually taking advantage of this.They interpreted any kind of self-assertion on the part of black men as really being about sexuality, you know, about taking white women.

BOB: There's a temptation to see this as kind of an interesting historical footnote, but it's more than that. It was really a watershed event for the politics and governance of North Carolina for a century.

TYSON: Oh, this is the most important political event in North Carolina's history, with the exception of the Civil War. When we had a coup in North Carolina and the federal government did nothing, President McKinley never even uttered the word, "Wilmington." What that did was send a signal that you can run black people out of public life in the South, no holds barred. And we quickly see this happening. Georgia had a very similar campaign in 1906 that was really modeled on what had happened in North Carolina, quite consciously, that becomes the heyday of lynching. This becomes the time of disfranchisement all across the South, where black people lost the vote. So it's not just a North Carolina event. It's really an event of national importance.

BOB: And the newspapers in Georgia and elsewhere in the South, did they mimic The News and Observer in its, you know, racial browbeating?

TYSON: The News and Observer, The Atlanta Constitution, The Times Picayune in Louisiana, The Washington Post, all the really, sort of the Democratic Party papers of that era followed this line. And this campaign broke a lot of ground with that, actually, because you don't see this type of stuff during slavery, for example. You don't see this idea in the white media that somehow the enslaved black men are a threat to white women. But when black men wished to be citizens, somehow the closer a black man got to a ballot box, the more he looked like a rapist. And you see these same images echoing into the 1970s and beyond.

BOB: Now, the commission didn't simply report what happened in this remarkable bit of history. It also offered suggestions for concrete steps that local government could take to begin to right some of the wrongs -- reparations for heirs of victims and for minority business grants, and so forth. But also, it suggested that the newspapers, which exist today under, you know, very different ownership and different ideology, should also address their own complicity with minority scholarships and, of course, a commitment to write about this chapter of history. Do you believe that newspapers should be in the reparations business?

TYSON: I don't know. Honestly, you know, I don't think that private payments to individual citizens are really going to do much to fix the damage that's been done. And I would also just say that The News and Observer, really, since 1998, on the 100th anniversary of the Wilmington race riot, has spent a lot of newsprint reporting on their own role back in the white supremacy revolution. The Greensboro paper and the Charlotte paper have done the same thing. So I don't think that they bear any great stigma. They've been very honest about how things were.

BOB: Well, Tim, thank you very much.

TYSON: Thanks, Bob. I enjoyed being with you.

BOB: Timothy Tyson is senior scholar for the Center of Documentary Studies at Duke University. He is also the co author, with David Cecelski, of "Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and its Legacy."