America's Lost Anti-Corruption History

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield. So the big story this week concerns, yet again, the Trump administration’s undisclosed entanglements with Russia. It's worth remembering that the Rosetta stone for all of the Russian mysteries may reside in the president's tax returns, which, of course, Trump has refused to release. Legal scholar Jed Shugerman believes that the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause could shake those tax returns loose and that state attorneys general have the standing to sue to get them. Shugerman teaches law at Fordham University School of Law. Jed, welcome back to the show.

JED SHUGERMAN: Thanks for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: You want state attorneys general where the Trump organization does business, particularly New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, to file suit against the company under the Emoluments Clause. But that clause is in the US Constitution. Is it really a matter for individual states?

JED SHUGERMAN: State attorneys general, not only in New York but throughout the country, have the legal power and the legal duty to make sure corporations are following the rule of law, not just state law but federal law and constitutional law, when it comes to anticorruption.

BOB GARFIELD: And by so doing, actually get access to the tax returns by subpoena or by the discovery process.

JED SHUGERMAN: Discovery should be able to get the financial records, the debt records and the tax returns to enable the judicial system to look at the full picture. So the first step is important in terms of just our basic importance for the public interest of transparency in government.

BOB GARFIELD: But you're also interested in the case itself, not just the taxes.

JED SHUGERMAN: The second step is looking at remedies here because it's important for us to see how foreign countries are using payments and debts as part of manipulation of the financial picture. Then that also connects to what's going on behind the scenes with this very bizarre behavior of, of the Trump campaign, to now the Trump administration, of being so solicitous and having so much flexibility to the Putin regime.

BOB GARFIELD: So whether or not it proves a high crime or a misdemeanor that the Congress is obliged to deal with, the tax return would be made public.

JED SHUGERMAN: Exactly.

BOB GARFIELD: It’s a very ingenious notion. Have you heard from the New York Attorney General’s Office?

JED SHUGERMAN: So other journalists have confirmed publicly that the New York Attorney General’s Office is looking at this proceeding, and several news outlets have looked at this and I think they are optimistic.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman was terrific in taking the lead against the Trump Corporation in a fairly similar kind of question about fraud. It wasn't just the victims of the fraud with the Trump University, it was also Eric Schneiderman who pioneered a public suit. And so, if he was willing to take on Trump University, he’s certainly willing to take on the Trump Corporation.

BOB GARFIELD: When you walk through the halls at school, do people look at you and go, ooh, look at you?

JED SHUGERMAN: I’ve never had an experience like this. Usually, like people sort of tolerate my legal history 19th-century archival navel gazing but now people walk up and they say, what's happening now? [LAUGHS] There's nothing like a legal historian suddenly stumbling into finding a way that history can be made relevant.

BOB GARFIELD: Jed, thanks very much.

JED SHUGERMAN: Terrific, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Law Professor Jed Shugerman is author of Shugerblog.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Last week, a Chinese-American executive named Angela Chen, who runs a company that explicitly helps cultivate US-Chinese business relationships, bought a nearly $16 million penthouse in a Trump high-rise in Manhattan. Trump owns this high-rise, so this Chinese-American dealmaker and professional courtier effectively paid Trump $16 million. [AUDIBLE BREATH]

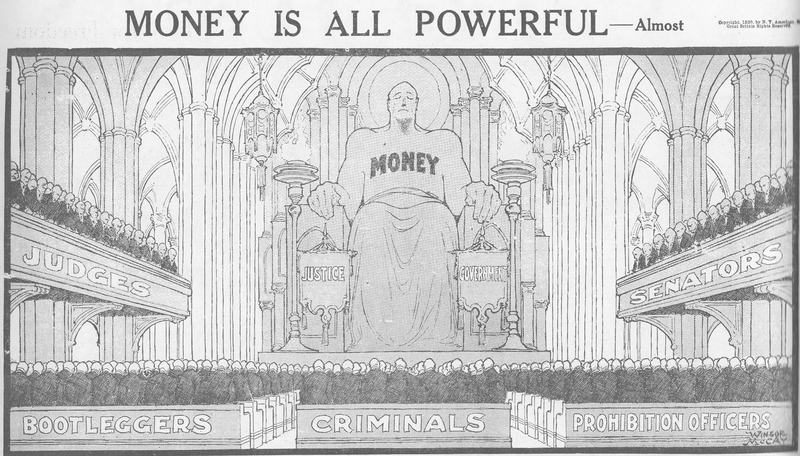

Before taking office, the president resigned from the Trump organization and left his sons to run the company but he still profits from his empire. The question of whether his vast business entanglements violate corruption rules clearly isn't settled, but it shows how far we've come from the original intent of the founders because for them, says Zephyr Teachout, author of Corruption in America, even a snuff box could be a source of suspicion. Zephyr, welcome to OTM.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: It’s wonderful to be on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I think Ben Franklin got ensnared by a snuff box, didn’t he?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yeah, Franklin had spent some time in France. He was well loved by the French court. In fact, a lot of people were worried about his loyalties. And then when he was leaving his diplomatic tour, he got this really glamorous diamond- encrusted snuff box and a portrait of the French king. And this caused a fair amount of concern and, in fact, was part of the reason that we have in our Constitution the provision called the Emoluments Clause, which prohibits taking gifts, as well as offices and titles of nobility, from foreign governments.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What’s an emolument? [LAUGHS]

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Basically situations in which you’re getting paid by foreign governments. I think the easiest way to think about it is something of value. This is one of those rare constitutional clauses that tells you how to read it. It includes this phrase “of any kind whatever.” And it’s really clear from reading contemporary understandings of the word “emoluments” that it covered a broad range of situations, including business enterprises.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why were the founders so concerned about corruption? You call it “their constant obsession.”

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: These are not naïve writers of our Constitution. They've experienced what they perceive as the intense corruption of Britain and they're all steeped in the story that Rome was torn apart from the inside by corruption. It’s saying, we are not going to engage in this culture of having financial relationships between diplomats and governments. It’s thumbing its nose at European practice. Even though they cared so, so deeply about developing their own trading relations, the anticorruption principle was so important to Americans that they were willing to sacrifice some comfort and ease in those relationships to have this anticorruption principle.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So, going back to the snuff boxes –

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - what did they decide? How did they thread that needle of forbidding gifts, while existing in a world where this was the general custom?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: The practice that developed was to allow Congress to basically bless gifts that came in. Congress would typically say, that's okay, you can keep that snuff box. Or when John Jay got a horse from the government of Spain, Congress gave Jay permission to keep the horse. This congressional check plays this really important role because it brings the relationship into the daylight. The American public, through Congress, gets to understand what was the nature of the gift. And also then Congress provides this important check, if there's anything suspicious, if there's any sense that this might actually lead to either an explicit bribe or to influence that would really undermine the integrity of our decision making.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In your book, you emphasize - and this is really important - that the founders forbid presents, not bribes. No exchange or agreement is required to bring it within the ban.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: It’s really clear that the framers did not think that corruption was just quid pro quo or explicit exchanges. They really understood how humans can be tempted to betray their loyalties, without even really being aware of it. So you need rules that, you know, in law we call these “bright line” rules or prophylactic rules, rules that basically say, you just can't do this category of behavior because there's a significant likelihood that if you're in this category of behavior, something wrong is gonna happen. So the category is taking gifts or payments. We’re not going to necessarily know which ones are influencing, nor are we going to easily discover which ones there might be an agreement around, but we need to ban the category so that we don't risk corruption.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But the founders’ anticorruption vision quickly ran into problems, not in Europe but on our own shores. I’m thinking of a word that if we were alive 200 years ago, you say we would all have an opinion on, Yazoo.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yazoo, yes! The Yazoo scandal really occupied the press and the public, that everybody had a position on Yazoo. So Yazoo refers to the lands in western Georgia, and the Georgia legislature gives away millions of acres for pennies on an acre to land speculators.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: It turns out basically all of the lawmakers who’d voted for this land giveaway were getting paid by the land speculators.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, the public threw out every lawmaker who’d voted for the deal, right?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yes, and that wasn’t enough. They [LAUGHS] actually had a bonfire –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- in the capital to burn the bill. And the new lawmakers immediately passed a law saying, that law was not a law because it was passed through bribery.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You can burn the bill and you can pass a law, but you don't get rid of the larger issue –

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - at least not in this case.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: That's right. The larger issue here is whether a law stops being a law because it was passed, in part, because of corruption. And this case goes on for years, finally makes it to the Supreme Court. And one of my favorite facts about this case is it’s the only case I know of where one of the litigators needed time to sober up halfway through oral arguments.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

And basically, the, the question was, who really owned the land, at this point? Was it still held by the people of Georgia or was it held by the people who had bought their land ownership from the speculators?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So the speculators that had bribed the Georgian legislators sold the land to people who thought they had a legitimate contract, and basically the Court said the contract superseded the anticorruption concerns raised by Georgia.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yeah, that's right. Justice Marshall who, by the way, had been a land speculator himself –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- said, it’s so sad that corruption has crept into our young Republic but it's sort of beyond the scope of this Court to pass judgment on what was a fundamentally corrupt contract and what was not. And the reason I find this episode really interesting is, in part, because it shows the awkward relationship between law and corruption. But really until the 1970s, court after court after court understood that protecting against corruption inside our country was one of the jobs of our country and was one of the greatest threats to our country. And then you see that kind of drop away really in the 1970s.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So take us there. What happened?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: So in 1976, the Supreme Court decided a really important case, Buckley v. Valeo, and struck down some campaign finance laws and set up a two-step process that we’ve really been living inside ever since. The first step is to ask, when there is a campaign finance rule, does that campaign finance rule infringe on freedom of speech? And the second step is to say, if it does, does it, however, serve an anticorruption interest? Suddenly, it really matters what corruption means because if corruption just means explicit quid pro quo, then a lot of what we think of as anticorruption laws are gonna get struck down.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So back in the days of the founders, they recognized that something could be corrupt even if it wasn't illegal. Now, you have to find an explicit exchange of something for something, a quid pro quo. And only a complete boob would get caught doing that, so much of this exchange is either behind closed doors or through intermediaries or is just assumed. So the kind of ambiguity in human nature, the indirect influence that the founders saw as corruption is now, strictly speaking, only if you have sold your office or your vote.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: No, that's right. And the loss is enormous. It’s, it's certainly a loss of a central part of our heritage as the country. We were founded on an anticorruption passion. But it was also incredible wisdom. It was an understanding that corruption is this very serious threat to self-government. And we’ve certainly felt the effects. We’ve felt the effects in the super PACs that have arisen since Citizens United. And we, as citizens, are left with fewer and fewer tools to fight corruption.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Which brings us to now. You're currently working on behalf of a group called Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, or CREW, trying to revive those long-lost anticorruption traditions by suing Donald Trump for violating the Emoluments Clause. What makes you believe that that could possibly work, especially without his tax returns and especially without standing?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: There's a lot of really hard, complicated, interesting corruption law questions. Donald Trump’s violating the Emoluments Clause is not one of them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm!

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: It is really straightforward that he is violating the Constitution and began violating it on the day he took office.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Well, there's four different ways in which he's basically getting things of value from foreign governments. The first is through the Trump Tower in New York City. The Chinese government, through the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, is one of the largest tenants in Trump Tower. So we basically have the Chinese government putting payments into Donald Trump's pockets. The second flow of emoluments, dignitaries from foreign governments staying in Trump hotels.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: The third is through The Apprentice and The New Celebrity Apprentice. In two countries, at least, the payments for royalties around The Apprentice come from government-owned entities. And then the fourth area is all the Trump organization developments around the world require government action, whether in Turkey or India or China, and the governments are in a position to make our president richer or poorer.

I think the important thing to understand is that the Emoluments Clause is a “bright line” rule. It’s like a speed limit. If the speed limit is 55 and someone's going 68, they don't get to turn to the cop and say, well, the roads were dry and nobody else was around, therefore, it isn’t a violation. This is a safety rule, right? If a federal officer is taking payments from foreign governments, the federal officer doesn't get to turn around and say, oh well, in this particular instance I wasn't getting influenced. It doesn't matter. You violated the rule.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Well, let me ask you this: The clause says that Congress has to approve, right?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: That’s right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So if Trump wanted this to go away, couldn’t he just get the Congress, which is pretty supine these days, to just approve?

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Yeah, it’s quite striking that he hasn't gone to Congress to ask for their approval. To do that, he would have to reveal the full extent of the nature of the nature of the payments. Congress could either accept and say, you can keep those, or reject and say, you can't keep those. It’s certainly a direction that Trump could be undertaking but, instead, he is just violating the Constitution every day.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Zephyr, thank you so much.

ZEPHYR TEACHOUT: Thank you so much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Zephyr Teachout is a law professor at Fordham University and author of the book, Corruption in America.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess and Jesse Brenneman. We had more help from Micah Loewinger, Sara Qari, Leah Feder and Kate Bakhtiyarova. And our show was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Terence Bernardo.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schacter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone,

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.