BROOKE GLADSTONE: In his piece for the National Review, Kevin Williamson calls poor white America the scene of negligence and incomprehensible malice, that, quote, “the truth about these dysfunctional downscale communities is that they deserve to die,” and he refers to, quote, “family anarchy,” which is to say the whelping of human children with all the respect and wisdom of a stray dog, savage but to Nancy Isenberg not shocking.

NANCY ISENBERG: That is a really, really old insult. The poor were often compared to curs or a mongrel dog, and these were seen as an inferior breed. You know they usually would compare the cur to the hound, so a hound is a legitimate dog that works, a cur isn’t.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Isenberg is the author of the upcoming book, White Trash: The 400-year Untold Story of Class in America. She says that the contempt for the poor, found in the National Review, can be traced back to the foundation of America, when the British, who called the poor “waste people,” saw the New World not as a land of religious liberty but as an ideal dumping ground.

NANCY ISENBERG: For the British, there were four ways you could deal with the poor. You hoped that maybe they would die from starvation or disease, maybe they would commit a crime and they would be thrown into prison. The other option was that you would drum them into service. They would be sent off to fight. Soldiers were also referred to as “waste.” And then the final way was that they would be sent to the colonies, outposts that needed people, but whether they survived or not was a [LAUGHS] secondary concern.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But there was a revolution and the founding fathers aimed to do away with hierarchy and aristocracy and replace it with liberty and justice for all. In your book, you look at this through the lens of Benjamin Franklin and, and Thomas Jefferson, but Franklin was not at all sympathetic to the plight of the poor. When he developed the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751, the perpetually impoverished weren’t welcome there.

NANCY ISENBERG: Yeah, and this was also a very classic pattern that existed in Great Britain. You would distinguish the poor who could be helped, those who can be put back into the workforce, and then others who he, again, sort of assumed were expendable, that there's no need to waste money or effort trying to rehabilitate them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And Jefferson held two different views in his mind at the same time. He had noble ideas of simple people, hard-working yeoman farmers, but he also referred to the poor as “rubbish”?

NANCY ISENBERG: Right, the reason he called them “rubbish” he’s saying it in the context of calling for how some selected young men from poor families should be given some kind of state-supported education; they would be raked from the rubbish. That phrase already assumes that if you - even if you rake a few, there’s still going to be a pile of rubbish left.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then you have the westward expansion in the 19th century and some new slang, notably, “squatter” and “cracker.”

NANCY ISENBERG: “Squatter” referred to them squatting down, sitting on land that they didn't own. And that is the exact opposite of the British notion of standing. And standing is the legal principle that defines one's territorial right to the land. So they’re squatters because they’re thieves. Jefferson referred to them as trespassers on the public lands.

And the word “cracker,” this comes from the English idea of cracking a jest, cracking wind. Also, there was the term “louse cracker.” A louse cracker was a lice-ridden, slovenly nasty fellow, and that's true by 1720. But it also takes us back to our favorite concept of idleness, because another important connection is that it was drawn from the idea of crack-brained, which denoted not only a crazy person but it was the English slang for a fool or an idle head.

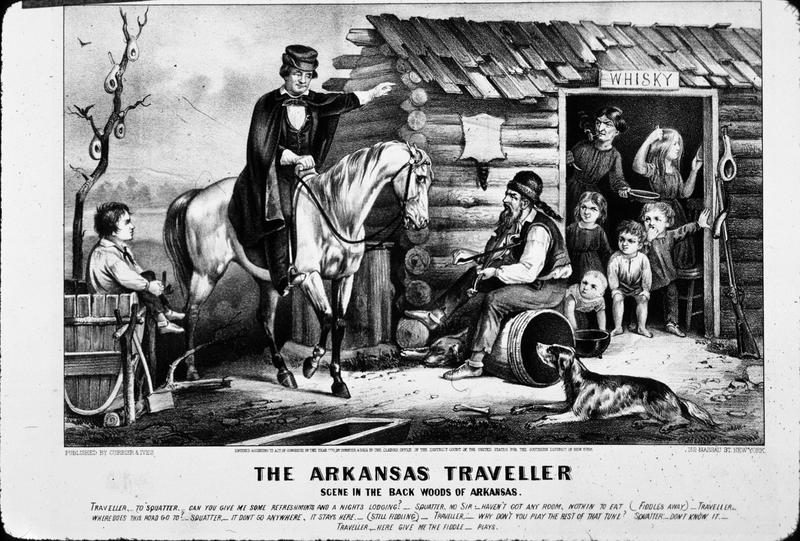

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even if squatters weren't particularly respected or trusted, they had to be pandered to every few years, in order to get people elected. And you mention the story of the Arkansas traveler from 1840.

NANCY ISENBERG: Yeah, the Arkansas traveler tells the story of a rich politician canvassing in the backcountry, and he asks a squatter for some refreshment. The squatter is seated on a whiskey barrel and he ignores him. And the politician is obliged, in order to get his refreshment, in order to get his vote, to, you know, jump off his horse, grab the squatter’s fiddle and show that he can play his kind of music.

And that, I think, eerily is a, a recurrent problem with our American democracy. What we really have is a democracy of manners, not a real democracy. And what I mean by that is that we accept huge disparities in wealth but we demand that our politicians sound like us or dress like us.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Eat our corndogs.

NANCY ISENBERG: Right, and it's all a performance. This is actually one of the things that I see Trump doing. The key to his appeal is the way he talks. You know, he’s blunt, he’s offensive, and his supporters view that as raw honesty. Even though he comes from a pampered life of wealth and privilege, every time he opens his mouth he affirms his allegiance to the working poor. That's what they like about him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, at this point, we should address the fact that yours is explicitly a history of the white lower class. You don't suggest that there wasn't fierce and violent racism in both the lower and the upper classes or that the treatment of poor whites, however horrible, was anywhere near as bad as those who were enslaved or racially discriminated against.

NANCY ISENBERG: Race is a very important category in my book. I talk about how prominent Southern politicians, particularly at the end of the 19th century, early 20th century, are seen as inciting poor white racism, supporting lynching. But one of the things that I think most people would find really surprising is that the Southern planter elite, before the Civil War, valued their slaves more than they valued white trash because slaves were at least productive.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And actually, the phrase “white trash” emerges around the time of the Civil War, right?

NANCY ISENBERG: Yes, because it's part of the language that is adopted by the Republican Party when they critique the South and the slave economy. This is when they begin to see the poor white trash as this dangerous offshoot. They see their children as old before their time, shriveled. They are described as a curious species.

And they ask this question, are these really Americans, how could America have produced such people? They are seen as dangerous, a group that, by the eugenics period, it’s not enough to just assume that we can dump them somewhere. Now you have to make sure that they can't reproduce.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There is one point in our history, you note, when there was active intervention to actually improve the lives of the poor. You had FDR's New Deal, though it was largely aimed at the white population.

NANCY ISENBERG: Suddenly, 20 percent of the population is out of work. You can't just blame one group for being an inferior breeder, you can't just blame them for somehow being lazy and idle, because now a large portion of the population find themselves short of their ability to be productive members of society. Suddenly people are willing to listen and think about the poor and look at them in a very different way. And this is one of the things that, you know, James Agee captured so beautifully, when he argued that to understand the poor we have to understand that we, the middle of the elite class who shame them, have contributed to the problems that they face.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the years of civil rights legislation, school desegregation, your book goes into detail about how the rest of the US thought of poor whites who were protesting such progress, as bigots, as inbred [LAUGHS], and so on. Many of them back in the 60s were racist, and, and certainly some Trump supporters are today, right?

NANCY ISENBERG: Yeah, I mean, this is a conundrum. They do subscribe to certain views that are undoubtably racist and you can't mask it and pretend that it's not there. It is very much a part of their thinking. But the other problem is when people want to blame poor whites for being the only racist in the room, as if they're more racist than everyone else, again, it reinforces the whole cycle again, that they don't deserve to be a part of civil society because their ideas are so backward.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Whereas many people have said basically Trump has put down the dog whistle and said things in plain English that have been said for years and years in politer language. And, and this brings us back around. Does the media‘s treatment of these people, in the assumptions the media make, reflect what you’ve seen play out over the last 400 years, when discussing the white working class?

NANCY ISENBERG: The problem is our media is just too dismissive and everything is reduced to a soundbite. When you refer to people as just being angry, it's another insult. When Jefferson used it [LAUGHS], he was referring to someone who's primitive and is so angry they can't speak. And there’s that same idea that they’re not advanced enough to understand their interests.

We have to begin to pay attention to class because people are always shocked when invisible people begin to speak. They say, where did this come from, how can this happen in America, how can this explain the way we imagine the myth of social mobility? So all we tend to get from the media is usually shock, and then it recedes into the background again and no one talks about it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What do we gain by directly addressing class issues and what do we lose by denying them?

NANCY ISENBERG: We have to talk about class because it essentially defines people in the most fundamental ways. You were born into a class station. You get privileges from your family, privileges from where you live. It is the essence of who we are. The most troubling thing people don't want to accept is that there are large numbers of Americans who do not experience social mobility, and it's not just because they’re inept or they’re lazy or they’re stupid.

I mean, we only had a real middle class in this country because of all the New Deal legislation, because of the loans given to housing, because of the, the growth of the economy. So it requires us to admit that we are in some way responsible for the existence of poverty, and that's what we don't want to admit.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Nancy, thank you very much.

NANCY ISENBERG: Well, thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Nancy Isenberg is the T. Harry Williams professor at Louisiana University and author of White Trash: The 400-year Untold History of Class in America, which will be out in June.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, don’t worry about money and politics. It turns out most of it is wasted.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.