About Those Self-Evident Truths

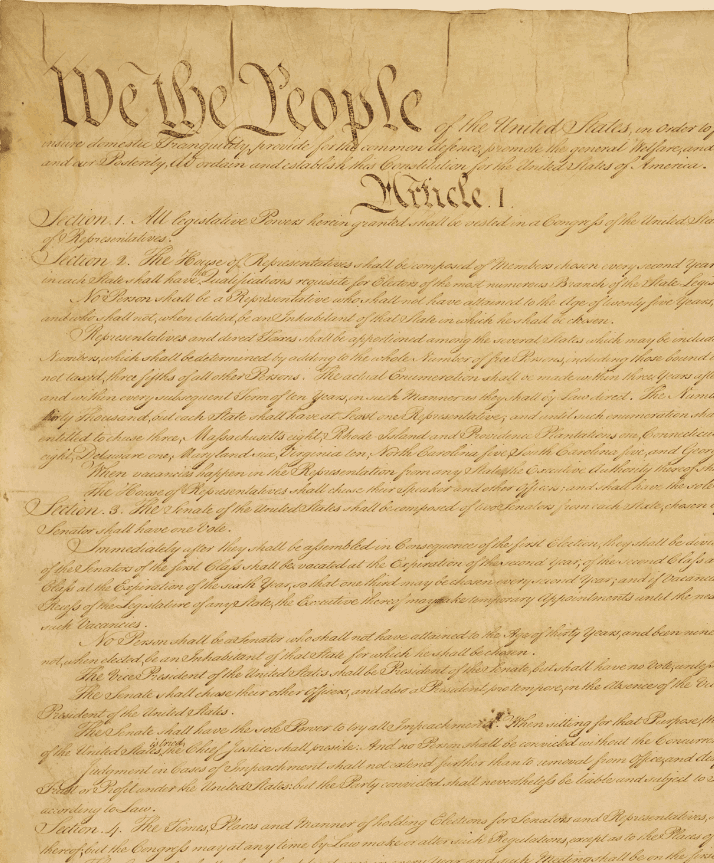

( The COM Library / flickr )

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We just heard of the effort by young plaintiffs to get real action on climate change. Not from Congress or the White House, but through the courts–by arguing from our founding documents and core principles. It seems that we are always going back to those, relying on those, reinterpreting those, in what seems to be lately an increasingly arduous effort to govern ourselves. In fact, that seems to have become the sour steam. Can we govern ourselves? John Adams didn't think so. He said that any political system with a monarchy, democracy, aristocracy, were all equally prey to the brutish nature of mankind. Jill Lepore–Harvard professor, New Yorker staff writer and prize-winning historian–has recently released a sweeping history of the American experiment called These Truths. I'm hoping she'll help me understand these contested truths and the media's impact on the everlasting argument over them. Thanks for doing this.

JILL LEPORE: Oh, thanks so much for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Alexander Hamilton wondered whether societies of men really were capable of quote establishing good government from reflection and choice or whether they are forever destined to defend their political constitutions on accident and force. You said that was the question when the Constitution was being sold in the autumn of 1787 and every autumn since.

JILL LEPORE: That is the question of American history. For Hamilton and for the framers of the Constitution, they had the past as a historical record available to them to know that all other experiments had failed. And that incredible sense of fragility with which they greet this new experiment. I mean, they have this enlightenment empiricism but they also have a lot of political wisdom from the study of history that leads them to believe that what their undertaking is quite a tenuous endeavor. If anything were almost crippled by our sense of the stability of our arrangement because it hinders us from undertaking reform when reform is so urgently necessary. So, the framers are not on bended knee worshipping the sacred document of the Constitution. In their lifetimes they're rejiggering, they're confronting its deep and fundamental inadequacy to address the problems of inequality that is failure to address the institution of slavery. I mean, that's a struggle for the first decades of American history and remains a struggle that we inherit through forms of racial inequality and racial injustice today, that would have been recognizable to them but that they didn't fix and they didn't foresee how to fix.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote that our founding truths were equality, sovereignty and consent. Newspapers were entirely and enthusiastically partisan. In fact, their delivery was subsidized, whereas in Europe they were taxed. Did they have an impact on the debate over equality, over the power of the central government versus the states, over slavery, over liberty?

JILL LEPORE: Our republic does not pre-exist newspapers. It is dependent on newspapers and that's where our party system comes from. Because the Constitution is generally printed by newspaper printers and often included in the newspaper as a broadsheet, you know, the kind of give away. Come get your free copy of the Constitution while you debate about ratification. And in most cities, there would be a newspaper printer who was a federalist who was going to support ratification and there'd be a newspaper printer who was an anti-federalist and they would battle it out. They believed, as Benjamin Franklin believed that what's meant by the freedom of the press is that printers should be free to express views so that readers could decide which view was right. That notion of the battle of opinion was how the ratification debate took place. And after the Constitution was finally ratified, that division remained in place. There were these federalist printers and then there were printers who were not really so down with the federalists and they become the Jeffersonian democrats. That division among printers builds the first party system.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ha.

JILL LEPORE: And already by the early 1790s, Madison can see that that's happening and he says well you know he thought that factions would be bad but it turns out newspapers are like the circulation of the blood of the body politic and as long as we have enough newspapers, we might be OK.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One constant tension in the American argument seems to involve the relationship between business and government. There were a lot of anti-corruption measures in the original documents. Jump ahead to the 20s, you have Herbert Hoover, the great engineer the Prado technocrat, he believed that nothing better represented America's philosophy of moral progress than the leaders of American business.

JILL LEPORE: Hoover is a deeply humane man. I mean, he came from nothing, went to Stanford, became a mining engineer and made an enormous amount of money. And then spent most of his life working as a philanthropist doing aid to refugees, but really he was chiefly a humanitarian. And he had the idea that other businessmen had the same moral probity as he did. And with that moral probity, what was necessary by way of reforming the political arrangements of the United States in the era of advanced industrial capitalism could be done outside of the realm of government through the moral leadership of the businessman. This is at a time when, of course populists who in the 19th century in the early 20th century are on the left not the right–so farmers and poor workers factory workers–are urging the federal government to rein in corporate power. And Hoovers one of these guys like, 'no we don't actually need to do that. Businessmen will restrain business because businessmen can be good people.' And it looks naive except if you think about how deeply Hoover himself in his own life was committed to that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He was president when radio was on the rise and he felt that government did have a role here in ensuring that radio reached its potential to make America he said literally one people.

JILL LEPORE: While he was secretary of commerce, radio was just starting. And radio when it started of course was really just kind of like point to point communication, like a telephone. Hoover's very far sighted about it. He holds a series of annual conferences at the White House–while he's secretary of commerce and continues that work when he becomes president–where he just brings together people from RCA, the Radio Broadcasting Corporation of America. And people from the press and from manufacturing to talk about what radio could do and what the federal government's role would be in it. And he comes to believe– a kind of in a kind of throwback to Madison's belief about newspapers, that newspapers would be like the blood in the circulation of the American body politic–that radio would be that new thing. And so we should think about how to make sure that it is available to everybody. By the end of the 1930s, everybody, really much everybody in the country has a radio. There's this incredibly powerful national network that is made possible by what Hoover set up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But it didn't make us literally one people.

JILL LEPORE: It didn't make us literally one people but I would say the 1930s are the best example of a national culture that is committed to a sense of shared burden. You always have to put an asterisk after that and say, 'OK, but like except for dealing with race and Jim Crow and lynch.' But nevertheless the sense of, 'we're all in the same boat,' that is part of the culture of the depression is actually advanced by radio.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Franklin Roosevelt pushed Hoover out of the White House in 1932. Roosevelt was famously great at radio. Obviously we'll never know exactly how much FDR's win hinged on the message and how much on the medium.

JILL LEPORE: Yeah, you know, one of the things that I had forgotten about FDR is that he had perfected the use of the radio when he was governor of New York. He would do the same thing, the sort of weekly radio addresses. And it was extremely effective for him. And one of the shrewdest observations I ever saw about that was made by Eleanor Roosevelt–who, you know, actually didn't have a whole lot of affection many ways for her husband. But she said, you know, 'when he was stricken with polio, that it affected the tone of his voice.' You could hear it in his voice, you could hear that he cared that he understood pain and that that served him incredibly well at the time when he was running for office in 1932. when the nation was really struggling when people just knocked down, bowed low downcast and hopeless. That there was something about Roosevelt's ability to communicate just in the breath that comes over the radio what his knowledge really was of that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I have a clip of him during that campaign describing two theories of prosperity and well-being.

[CLIP]

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT: First, the theory is that if we make the rich richer, somehow they will let a of wealth prosperity trickle through to the rest of us. The second theory– and I suppose the second goes back to the days of Noah, I won't say from the days of Adam and Eve because they had a less a complicated situation to face. But very, very early in the history of mankind, there was that second theory that if we make the average of mankind comfortable, and make them secure in their existence, then their prosperity will rise upward, through the ranks. [END CLIP]

JILL LEPORE: That sensibility participates in a demand of the entire population that we understand that we are in this together. And that's the piece of political rhetoric that we don't have anymore.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: After the global financial crash you quote Felix Frankfurter saying in 1930 that epitaphs for democracy are the fashion of the day and you quote a lot of other people on this. Did people think the American experiment was over?

JILL LEPORE: People were worried the American experiment was over. But more, they were worried that democracies around the world were over. And that the only one left standing would be the United States. And so there's a lot of pressure on the United States to figure out a way to not fall for the sake of everyone else’s, as well as--.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ha.

JILL LEPORE: --its own sake. By 1939, when they're building the world's fair.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

JILL LEPORE: This incredible pavilion, the world of tomorrow is the theme of the world's fair.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Outstanding landmark, it's the theme center. While the four freedoms. Speech, press, assembly and religion, all on constitution mall. Thirty feet high, they symbolize the four rights of free American, guaranteed by the Constitution. [END CLIP]

JILL LEPORE: But there's this whole pavilion of nations. It's like a stall or whatever, an exhibit for every nation around the world. And by the time the thing opens most of them have fallen to totalitarianism. And so they're sort of shrouded. Like there's just this visible reckoning with authoritarian regime after regime, after regime, taking over democracies. So for FDR, when he comes to office, you know, in 1933 there's this incredible complex situation where a lot of people say, 'you should take on the powers of a dictator to save the country from depression but don't really take them on because we actually need to still be a democracy.' But if we were really a democracy we ask the people how to solve the banking crisis, we won't solve the banking crisis. You know, so it's a very tricky moment that Roosevelt navigates, ultimately, successfully but there's a lot of concern. Because of course, you know, these fascist regimes were democratically elected. They've taken seize power and Roosevelt seized a great deal of power from the executive office.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You talk a lot about polls. And polls seem to have grown in power and influence during this period. I wonder if they said something about our troops or purported to or about democracy.

JILL LEPORE: Public opinion polling as we know it today begins in 1935 when George Gallup opened the American Institute for Public Opinion. And he's trying to offer measuring public opinion as the answer to fascism. Like fascists are going to use the radio to tell people what to believe. But pollsters will use other for, call people up to ask people what they believe. So we can know the public will at all times. Gallup publishes this syndicated newspaper column called America Speaks, runs all through the 40s and 50s and into the 60s. There's a lot of criticism of it but what I find so concerning about polling in that era–I mean there are many things I find concerning about it–but Gallup for instance didn't poll African-Americans in the Jim Crow South, ever. Because he knew they couldn't vote and he was like trying to say how the public will vote. So there's incredible sort of suppression of public opinion, right? It actually restricts the political conversation. From the start are these distorting effects of polling. You know, we see versions of that now as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then you had of course Dewey beats Truman.

JILL LEPORE: It's not just the newspapers that call that election wrong in 1948, it's TV, which is brand new. So when you get to 1952, there is this is fascinating merger of political problems and political solutions where, like with the radio which is surplus military equipment after the first world war, mainframe computers emerge as the intellectual property that's developed during the Second World War. They're built to crack codes and calculate missile trajectories. But the first commercial mainframe computer, the UNIVAC, is available in 1950 and they sell one to the US Census Bureau. And meanwhile television news networks are, 'well we would like to get some viewers on election night.' A lot of people now by 1952 have TVs but they don't know how to make election night interesting. What are they going to do? So, actually each network hires a different computer. One hires this thing called the robo--the Monabot. But CBS hires the UNIVAC to predict the outcome of the election between Eisenhower and Stevenson and it's actually, it would just be a fantastic sitcom. It's a crazy madcap, harum scarum kind of disaster of a night with Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow competing with this gigantic brain.

JILL LEPORE: They seemed really invested in a kind of power to show America to itself. And this seemed to disgust the legendary newsman from CBS, Edward R. Murrow in 1952 after the election of Eisenhower. He said that the people surprised the pollsters, the profits, the politicians. They demonstrated that they are mysterious and their motives are not to be measured by mechanical means. The fact that the machine was defeated was a victory for democracy–it sounded like.

JILL LEPORE: That's how Murrow wants to believe it worked out.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ha.

JILL LEPORE: But that's not how it worked out. What Murrow was worried about in 1952, was the automation of the practice of democracy. That actually has come to pass. And what I argue later in the book is that the polarization that we are experiencing today in the United States was built manually. Kind of voter by voter by hand in the 1970s and 1980s by campaign consultants chiefly. But in the last 20 years, it's become fully automated. It's not necessary to do the same set of hand by hand work to animate your electorate to the point of blind rage. That's done by machine now. That is exactly the kind of thing that Murrow was worried about a long time ago. And so if that's the case, then are the people sovereign? Are we consenting to be governed? Do we have natural rights? What is the nature of our political equality? There are all kinds of questions we have to ask ourselves in these different circumstances.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So what was the impact then of television on our truths and the debate over them? Your book directs us to this:

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Lower taxes.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Higher taxes.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Record employment.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Unemployment.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Peace.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: War.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Highest wages.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Lower pay.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: States' rights.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Centralization of government.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Whoa, stop. I've tried. I've listened to everybody–on TV and radio. I've read the papers and magazines. I've tried but I'm still confused. Who's right? What's right? What should I believe? What are the facts? How can I tell?

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Well my friend if it's any consolation, you're not alone. Many voters are in the same boat right this minute. Words have been flying at you hot and heavy. You've heard the pros and cons, the cons and pros of both sides. You've listened to people you believe in and people you've never heard of. It's not surprising that are confused. But beyond all the words, beyond all the claims and promises, there's actually just one big thing on which most people base their final decision. The man. Take this man, Dwight David Eisenhower. Ike, soldier, statesman, president, American.

[END CLIP]

JILL LEPORE: Oh, they don't make them that good anymore.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, up until the word Eisenhower, you could have heard the very same thing today.

JILL LEPORE: Oh absolutely, no absolutely, especially 'what are the facts, how can I tell.'

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then don't worry about any of that stuff.

JILL LEPORE: Yeah, well, you know, you wouldn't really hear is actually the voice of authority at the end. You would have to use it from some sort of ordinary Americans saying something like while washing the car in the driveway with the puppy. 'Oh, well I really like Eisenhower.' What you are listening to there is a politics of mass persuasion which doesn't really get a star until the age of mass production. It was followed by the age of mass consumption and politics becomes a business. Political campaigns are run by people that start out in advertising agencies and they use the tools of modern mass advertising. They use those tools to sell candidates to voters the way they sell soap or dishwashing detergent. And that's what you get. It's actually really, really weird when a candidate but that is what we do now. I mean, I guess we do something different on kind of online world. Because that is actually not an attack on Stevenson, notably. It's very sympathetic with the voter who's like, 'you know, what I don't know. Mean these people both seem reasonable.' It doesn't require demonizing Adlai Stevenson.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was television doing to our debate over our fundamental truths in mid-century.

JILL LEPORE: Television was trying to do the same things that Radio had tried to do. Network news was for sure trying to cultivate debate and cover politics. And on the whole, the age of network news 48 to 78 say, was characterized by significantly less political polarization than either before or since. There's a lot that you could point to that's concerning about television in those years, but if you're interested in political moderation that's what you get. Where our era of polarization really begins is when the remote control is invented in the 1970s and cable news first starts. People who aren't interested in politics stop voting because they tend to vote according to this theory. During the golden age of television because when they come home from work at 6 o'clock the only thing that's on is television news. They pay more attention because it's on TV and they tend to vote and they tend to be moderates. And when cable starts, then suddenly when you come home from work there are 260 things to watch and you can watch reruns of Gilligan's Island. And then you stop voting because you kind of stop paying attention. So that moderates drop out of the electorate in really significant ways with the rise of cable television. There were all these kind of curious little moments where we see quite clearly how symbiotically our media and our politics have grown and how inseparable they are.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You conclude by saying what we feel every day, that the American experiment hasn't ended. What do you think are the truths that will ultimately hold it together? Or what do you think we're really fighting over still?

JILL LEPORE: I think what's been unsettling for partisans on all sides and for moderates as well, is the sense, in recent years that really everything is back on the table. Things that appeared to have been political settlements of earlier generations seem now to be revealed as not settled at all. That made it very difficult to end this, end this book. I also was committed in writing the book to insist that the United States is founded on the idea of equality but it is equally founded on the idea of inquiry. That an obligation of every citizen is to inquire into why the world is the way it is and how it can be made better and what it is about our national creed that sticks and works and what it is about our political practices that need reformation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That sounds great but was that really a fundamental truth?

JILL LEPORE: Yeah. The Declaration of Independence, 'let facts be submitted to a candid world.' Our founding documents are full of commitments to proof and evidence and inquiry. And they are themselves the product of people who read a great deal of history because they knew that that's where you could sort of see, 'well, what happens when you do this and what happens when you do that. And what happens when a society is arranged this way and what happens when this arrangement is tested.' So to end, you know, 900 page account of American history with my verdict on the question that Alexander Hamilton asked. You know, can we rule ourselves? Can any people rule themselves with reflection and reason and choice in election? Or are we all just fated to descend into being ruled by accident and force. I can't answer that. The point of the book is to ask readers to reckon with that question. But that is an obligation of citizenship.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jill, Thank you so much.

JILL LEPORE: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jill Lepore is the author of These Truths: A History of the United States.