BROOKE GLADSTONE: We’ve spent a lot of time this hour on the practice and the ethics of persuasion. Hiding advertising messages under the mantle of journalism is not ethical, but it's legal. Out and out propaganda against Americans by Americans is neither.

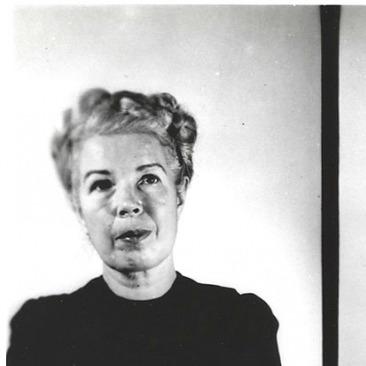

On March 10th, 1949, a jury found Mildred E. Gillars guilty of treason. She died 25 years ago, last month. Many of the people who knew her late in life, years she spent quietly in Ohio, had no idea of her past. They didn't know that between 1942 and 1945, Gillars was better known to the world as Axis Sally, a Berlin-based radio host on German state TV, broadcasting Nazi propaganda.

[CLIP]:

AXIS SALLY: And the enemies are precisely those people who are fighting against Germany today and, in case you don’t know it, indirectly against America too because a defeat for Germany would mean a defeat for America. Believe me…

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In 2011, we spoke to historian Richard Lucas about his biography of Gillars called, Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany.

RICHARD LUCAS: Her broadcasts were basically two pronged, one to American women at home, and also her broadcasts were aimed at the American soldiers fighting on the frontlines.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And the messages for the people on the front lines?

RICHARD LUCAS: “We know where you are. We know you’re coming and you’re going to be destroyed.” The other messages included, “Your girlfriends, your wives are home with the 4Fs, the slackers and are being romanced by them.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Frequently in her broadcasts to the Americans at home, she's exhorting them to use a kind of tough love to defy the country.

[CLIP]:

[STATIC NOISE]

AXIS SALLY: If your child behaves badly, do you agree with this misbehavior? Do you say to yourself, my child, right or wrong, I don’t care what he does? No, you don’t. You try to correct that child. You try to make him a better citizen. Well, and what is a country? A country is only made up of people after all. Do you say my country right or wrong. No girls, that is false sentimentality and I do not say my country, right or wrong. I love America but I do not love Roosevelt and all of his “kike” boyfriends who have thrown us into this awful turmoil.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She would broadcast the names and injuries or deaths of soldiers. She would say to their mothers or wives, that’s what you get for supporting the war?

RICHARD LUCAS: Yes, and I have some examples of that here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

RICHARD LUCAS: How many very mutilated boys have I seen? And they’ve said to me, “I don’t care how I get back, just so I get back.” You see, that's the way they think now. What do you suppose they'll think in later years when there are no jobs for cripples? And it goes on. She tells a mother whose wounded son is in a German hospital, “Well, Mrs. Lupole, you’ve seen nothing of this war. You only read Jewish propaganda in your newspaper, but if you've been listening to this broadcast then you know that for many weeks I went from war hospital to war hospital, and I saw your boys. There are hundreds and hundreds of thousands of them, scattered all over the world, asked to sacrifice their youth, asked to sacrifice their future, because when they get back they will be in no state to take up a job of any consequence.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, who was Mildred Gillars? I know she had a lousy childhood.

RICHARD LUCAS: She did have a terrible childhood. She lost her biological father at the age of seven. Her stepfather was a itinerant dentist who became addicted to alcohol and the laughing gas in his practice, and I also found that she perhaps was abused as the stepdaughter, sexually abused. She could not wait to get away from the stepfather. And she went to Ohio Wesleyan University and came under the influence of a man who told her that she should pursue acting. And she went to Cleveland, with 20 dollars in her pocket, and she became an actress, and then within a year she went to Broadway. And she was in George White’s Scandals, the vaudeville show.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So things were going pretty well.

RICHARD LUCAS: On and off, yes. But she had this innate ability to mess up a good situation. She always wanted to do Shakespeare and Ibsen. If it was comedic material, she didn't want to remain there. And at that point in 1929, 1930, when the Great Depression took hold and vaudeville was dying, it all fell apart.

She became involved with a man, British and Jewish, and he was a foreign officer for Britain. He was assigned to Algiers and she followed him to Algiers. And after that relationship fell apart, she went to Europe, met her mother and they ended up in Berlin in 1934. And that's where she sees the Third Reich in its infancy, sees the enthusiasm, sees the employment opportunities, and she decides to stay.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She later said that she feared poverty in the US and she wanted a German man that she'd been dating to marry her.

RICHARD LUCAS: Yes. In 1941, she was counseled by the US consulate to return back to the United States. She had just started working for the Nazi radio, and she was involved with a man named Paul Erickson. He was a German citizen. And he told her, if you return to the United States I will never marry you. She was already 40 years old at the time. She decided to remain, and then when Pearl Harbor occurred she was in a position where she could not go back. Paul Erickson, the fiancé who was going to marry her, was sent to the Eastern Front and killed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And that was that, and she was stuck.

RICHARD LUCAS: Yes, and then Max Otto Koischwitz, a former Hunter College professor, who fled back to Germany with his entire family in 1939, right before the outbreak of World War II, became her manager. They had an illicit affair. He was married with three daughters and one on the way. He wrote her scripts, directed her propaganda, encouraged her, even telling her that Shakespeare was propaganda.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When she finally went on trial, did her prosecutors present evidence of her impact?

RICHARD LUCAS: One by one, prisoners of war and families of prisoners of war had come out to say that their families had heard the broadcasts. There were witnesses from Germany who were called to testify that they were eyewitnesses to her treachery.

In the court, the judge and prior court cases had said it didn't matter whether anyone at all had heard her broadcast. It didn't matter if she said it on a microphone and no one heard it at all, she’s still liable for treason.

RICHARD LUCAS: And she apparently gave the performance of her life during her trial.

RICHARD LUCAS: She did. And when the prosecution played a recording of her saying, “American mothers, did you raise your sons to be murderers,” she collapsed in the court.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think she really fainted?

RICHARD LUCAS: No.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

She had a habit of swooning when it got a little – you know, a little tight.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How’d you feel about her at the end of this project?

RICHARD LUCAS: Conflicted. You can see in her time in prison how she changed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How many years in prison?

RICHARD LUCAS: Twelve.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And what was the change?

RICHARD LUCAS: She was a racist and anti-Semite when she came in, didn’t want anything to do with the other women. She was totally independent. She was actually put in Alderson Prison in West Virginia where Martha Stewart served her term. And she changed over that time. She converted to Roman Catholicism. She started to teach the other women in the prison. She ran the choir for the Protestants and the Catholics. And, and I really believe that she had a, a true conversion.

By the same token, she still denied knowing anything about the Holocaust ‘til the day she died.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: On the day she was found guilty, she said to reporters, “I wish those who judge me would be willing to risk their lives for America the way that I did.” Did she vary from that position?

RICHARD LUCAS: No, she never varied from that position.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So let me ask you, Richard, why are you conflicted?

RICHARD LUCAS: I'm conflicted because I believe that there is redemption, and I believe she had some measure of it.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

I believe that she changed remarkably in her later years. When you spend the first two-thirds of your life seeking nothing but fame and spend the last third seeking nothing but obscurity and privacy, I think you’ve, you've changed, and changed in a major, major way.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Richard, thank you very much.

RICHARD LUCAS: Thank you so much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Richard Lucas is a historian and author of Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]