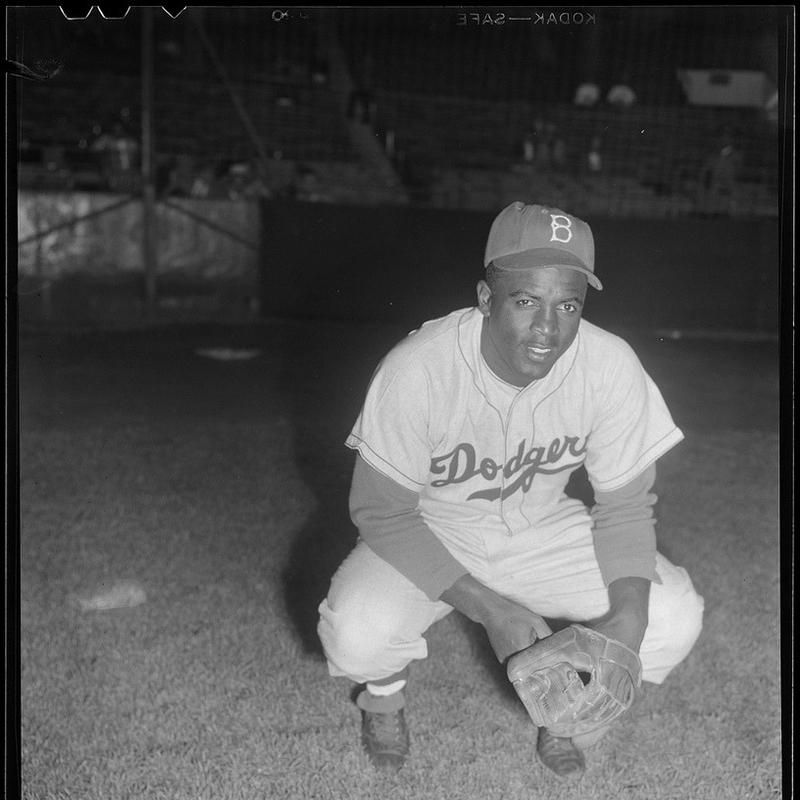

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It's hard to discuss breaking down barriers in sports without at least once invoking the Brooklyn Dodgers, specifically Jackie Robinson, who broke major league baseball's color barrier 66 years ago this month. His story is the stuff of legend, as in the new film named for his number, “42.”

[“42” CLIP]:

CHADWICK BOSEMAN AS JACKIE ROBINSON: You want a player that has the guts to fight back?

HARRISON FORD AS BRANCH RICKEY: No, I want a player that has the guts not to fight back.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Robinson’s legend took shape and took off from the very start.

[CLIP]:

JACKIE ROBINSON: Give me a uniform, give me a number on my back. I’ll give you the guts.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Just three years after his debut as a player, he starred at himself in “The Jackie Robinson Story.”

[CLIP]:

BRANCH RICKEY (MINOR WATSON): Suppose I collide with you at second base and when I get up I say, 'You - you dirty black so-and-so,' what do you do?

JACKIE ROBINSON (AS HIMSELF): Mr. Rickey, do you want a ballplayer who's afraid to fight back?

BRANCH RICKEY: I want a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back!

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Throughout the more than six-decade celebration over Robinson’s achievement, the chief interpreter of it, the strong and steady hand behind both the man and the myth, is virtually unknown.

Los Angeles Times sportswriter Bill Plashcke has recently penned a portrait of this largely invisible man.

BILL PLASHCKE: When he was 17 years old, he played in a really important baseball game and a scout came, and he was the, the pitcher and there was a white catcher and a scout came and said, you know, I’d like to sign you to play for professional baseball, but you’re black, I can’t do it. So he, he signed the white catcher instead. [LAUGHS] From that moment on, Wendell Smith said that he was going to try to break the racial barriers in baseball, however way he could it. And he couldn’t do it by playing, so he decided to do it by writing. So he was a sportswriter who was also an advocate.

So it was Wendell Smith who first came to Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, and said, “Hey, I got a guy you should look at to be the first black in baseball, and that’s Jackie Robinson.” Branch Rickey decided that Jackie would be the best candidate to break the barrier. One of the first people he called was Wendell Smith and he said, “Listen, we want you to travel with him.” So they traveled together for the first two years of Jackie’s pro career. It would be unthinkable today for a newspaper to allow a writer to accompany just one player all the time and take care of him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He ghost wrote Robinson's weekly newspaper column.

BILL PLASHCKE: Yeah, he was his voice. He would also counsel Robinson on how to deal with the media and, “Okay, they’re gonna ask you this, you need to say this.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote that when Robinson resisted, Smith would remind him that he himself was enduring the same racial slights, only without the stardom.

BILL PLASHCKE: That was the most – to, to me the most compelling part of the movie, and which mirrored real life exactly, from my research, was where Wendell picked up Jack at the train station and Jack’s like, “Wendell, I get tired of you, you’re always with me, you’re always – trying to counsel me. You have no idea what I’m goin’ through.”

And Wendell stopped the car and looked at him and said, “Jack, why do you think I sit and stand at the games, why do you think I type my stories with a typewriter on my knees in the bleachers? Why do you think I’m not in the press box? Because I’m not allowed in the press box, because I go through the same stuff you do. Open your eyes.”

I can’t imagine as a sportswriter not having access to a place to, to write your story! I can’t imagine that. He had to cover the team a whole year before the Baseball Writers Association of America even let, you know, Wendell join.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the Courier, the black paper for which Wendell was still writing even as he was traveling with Robinson, he encouraged black fans to conduct themselves well at games, and he downplayed the ugly impact of racial incidents in baseball.

BILL PLASHCKE: That’s what he counseled Robinson, and that’s how he wrote. He write it like, “You know what, we – we’re supposed to be here, we belong here. Let’s act like we belong here, and let’s act like anything that happens to us, we can handle it.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Describe what he looked like.

BILL PLASHCKE: Wendell had, you know, big glasses and, you know, he was a slightly built man and just kind of blended in. He wasn't loud and he wasn't abrasive. And it was interesting - I'm describing him mostly from the one photo I’ve seen of him and from his – what his wife has told me because nobody really knew what Wendell looked or sounded like ‘cause they didn’t take pictures of sportswriters back then.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He did later become an on-air sports broadcaster for WGN, right?

BILL PLASHCKE: Fifteen, twenty years later, yes, he became an on-air person. By then he was a very huge figure in the African-American community and as far as in the media. He also - in Chicago, Wendell Smith also wrote a series of columns that they thought should have won a Pulitzer Prize, about how, despite baseball being integrated by the early sixties, spring training was still segregated. Players could play on the teams but in the spring training in Florida they had to live in separate hotels, and terrible hotels. So he did a huge series about that, changed baseball. Baseball stopped going to those spring training sites in Florida that would not let blacks and whites live in the same place.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even though they didn't hang out after Jackie's brilliant career, they still remained tied.

BILL PLASHCKE: The last story Wendell Smith wrote – he was suffering from cancer and the last story he wrote was from his hospital bed. He wrote Jackie’s obit. And then a month later, Wendell died, as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why do you think Wendell gets written out of the story time and time again?

BILL PLASHCKE: Frankly, I, I must admit to you, until recently I had no idea of this man’s great impact. The producers of the movie told me they didn’t know until they studied it. We thought it was Jack against the world, certainly would not imagined it to be a sportswriter.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bill, thank you very much.

BILL PLASHCKE: Thank you very much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bill Plashcke covers sports for the Los Angeles Times.

[1949 CLIP/WOODROW BUDDY JOHNSON & COUNT BASIE SINGING "DID YOU SEE JACKIE ROBINSON HIT THAT BALL?"]

Hey, did you see Jackie Robinson hit that ball?

It went zoomin ‘cross the left field wall.

Yeah boy, yes, yes. Jackie hit that ball.

[SONG UP & UNDER]