BOB GARFIELD: It goes without saying that the digital revolution gave us life-changing innovations the world had not seen since the industrial revolution. Now, imagine yet another transformational development merging the digital and industrial revolutions. I refer, of course, to 3D printing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, like “Star Trek’s food replicator.

[CLIP]:

TOM PARIS: Tomato soup.

[COMPUTER TONES]

COMPUTER: There are 14 varieties of tomato soup available from this replicator, with rice, with vegetables, Bolian style, with pasta, with -

TOM PARIS: Plain.

COMPUTER: Specify hot or chilled.

TOM PARIS: [ANNOYED TONE] Hot! Hot, plain, tomato soup!

[TONES][END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, of course, the Galaxy’s most famously replicated smokin’ beverage.

[“STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION” CLIP]

CAPTAIN JEAN-LUC PICARD: Tea. Earl Grey. Hot.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm.

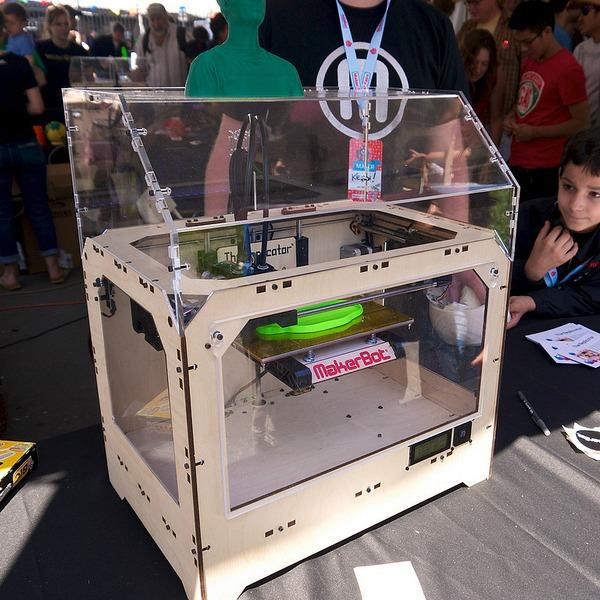

BOB GARFIELD: Yeah, but right now, here on earth. For instance, at this moment, early adopters already can make a wrench, using a blueprint downloaded for free from the internet. Instead of clicking Print, they click Make, So what happens when everyone can be a manufacturer? Chris Anderson, former editor of Wired Magazine is the author of Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. He described what someday soon we’ll all be able to do from our desktop.

CHRIS ANDERSON: You know, the inkjet you’ve already got on your desk takes pixels on the screen and then spits it out in little blobs of ink on paper. Imagine if it just kept doing it layer after layer, and rather than ink it was using something else, like little bits of plastic or metal or glass and things like that, and that it built up a 3D object, and that you could just pick an image on the screen and press Make, and 20 minutes later you would actually have the thing you could hold.

BOB GARFIELD: Okay, so we can print out a wrench. Please explain to me why that is revolutionary.

CHRIS ANDERSON: We’re right where desktop publishing was in 1985. There was software that would allow you to do things that used to require a typographer’s union. How extraordinary to have added the word “desktop” in front of a word that was previously industrial? It didn’t change the world by itself but what it did do is it kind of liberated the concept of publishing from industry and put it in the hands of regular people. And then along came the Web, and publishing went from generating paper on your desktop into a button and your browser and with a single press you could reach eight billion people, theoretically. [LAUGHS]

The 3D printer is the first step. It has liberated the idea that yes, you can make something. You don’t need to be a machinist, you don’t need permission. You can press a button and something will come out. And it’s gonna take 20 minutes and it’s gonna be plastic. But to be able to go to the next stage, the Web stage, where you’ve got a button in the browser that says Manufacture, rather than Publish, that’s gonna happen sooner than it did.

BOB GARFIELD: For those of us, like me, who have a history of inability to have a vision of the future, give me an idea of the ramifications of the ability to press Manufacture.

CHRIS ANDERSON: When professional tools get in the hands of amateurs, they change the world. It is the explosion of participation and creativity and innovation that happens when you don’t need permission to use things, when it’s not hard, when people who are not necessarily trained in this but just sort of do it for their own reasons. That really is what the Web is. The Web is just a new way of working together online with people who otherwise wouldn’t have been allowed to in the old model because they didn’t have access to the tools.

Manufacturing is the biggest industry in the world. We’ve seen what the Web can do to media and we’ve seen what the Web can do to communications. Just imagine what the Web can do to the biggest industry in the world. And the moments when we’re empowered to do that experiment, to actually play that out, has finally arrived.

BOB GARFIELD: I, I guess I have to know if whether mere mortals can be trusted with the democratization of the physical world? Will they steal intellectual property from others? Will they make guns and nuclear triggers? I don't think you have to be entirely paranoiac to see a lot of negative potential consequences.

CHRIS ANDERSON: When the personal computer came out, you know, people first asked what they could do with it, and then they quickly had answers. And some of those answers were, you know, video games and some of them were spreadsheet and some of them were computer viruses. When the genie gets out of the bottle, you get a really wide spread of uses. Well, you can’t print a gun. You can print parts of a gun. I think that it’s actually a really bad way to make a gun, you know. First of all, it’s America. You can buy guns at Walmart.

It does raise challenges for intellectual property. As clear as copyright law is, it struggled to adapt to the digital age. And copyright largely affects the creative arts - words, pictures, video, music, etc. What about physical stuff though? How does copyright law apply? You know, what elements of this coffee cup is creative and what part is covered by other intellectual property law, like patents or trademark or not covered of all? And how many polygons is piracy?

BOB GARFIELD: I think you could make a pretty good argument that the digital revolution changed humanity. Do you predict the same for 3D printing and other digital manufacturing technologies?

CHRIS ANDERSON: I do, if the past is prologue. And, in fact, there are more people out there with good ideas for making stuff than there are currently making stuff. It won’t just be better products cheaper, but also new products, new categories we’ve never thought of.

BOB GARFIELD: Chris, thank you very much.

CHRIS ANDERSON: Thanks, Bob, it’s good talking to you.

BOB GARFIELD: Chris Anderson is the CEO of 3D Robotics and author of “Makers: The New Industrial Revolution.”