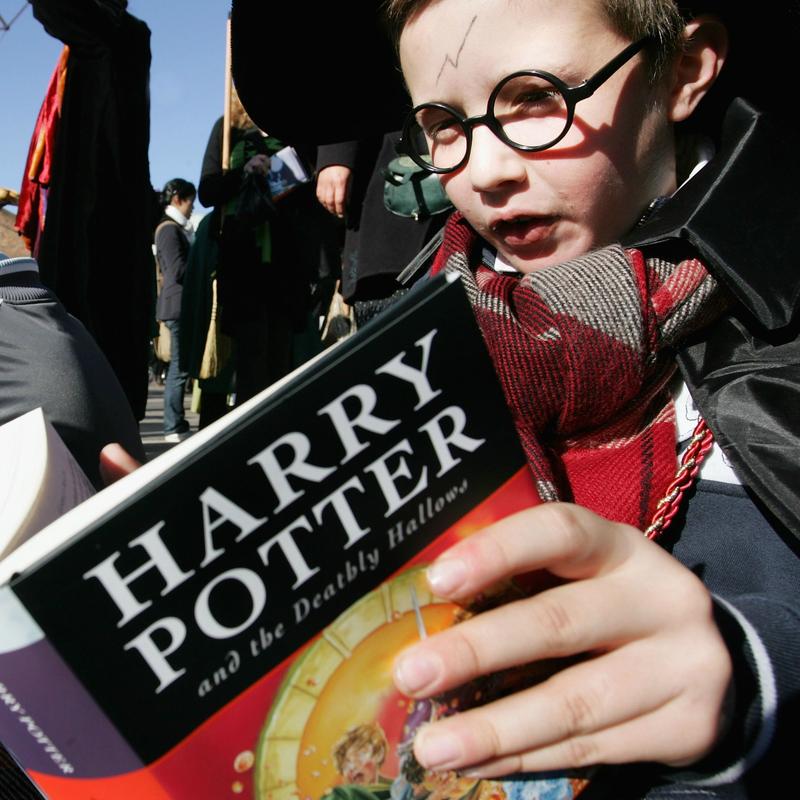

BOB GARFIELD: On Thursday, the New York Times reported that a member of the Baker Street Irregulars, a group of Sherlock Holmes aficionados filed a complaint against the Conan Doyle estate, arguing that homes, in his world, were in the public domain. And the Times quotes one lawyer, Darlene Cypser, charging that the estate, quote, “is going around bullying people.” She had self-published a trilogy about the young Holmes. She’s a writer of fan fiction, a genre that’s been supercharged by the internet, now awash in fan-created derivatives of everything from “Harry Potter” to “The Gilmore Girls,” sometimes with audiences exceeding a million.

Rebecca Tushnet also writes fan fiction, teaches law at Georgetown University and heads the legal committee at the Organization for Transformative Works, a nonprofit designed to protect writers like her, who, she says, are no longer shunned.

REBECCA TUSHNET: One thing that has really changed over the past few years is that copyright owners have really started to understand that fans are fans; they are a good thing to have. And one thing that fans do is they create more stuff.

BOB GARFIELD: If I'm a fan of, you know, let’s say Harry Potter and I do some sort of fan fiction, I'm free to go crazy with my versions of the characters and the developments. What happens when I try to sell those for a buck on my website?

REBECCA TUSHNET: There are such things as commercial fair uses. When “The Daily Show” runs clips from the news and comments on them, that's fair use. And it's possible to have fictional fair uses, as well. However, the bar is higher and it really would be a case-by-case determination. For example there is a preacher who wrote a version of Harry Potter in which Harry Potter came to Jesus and renounced magic because it was evil. Whether or not that's good, it clearly does have a critical message that comments on the original and is something that would never be part of the original. And that makes it have a good case for fair use, even if he then solicits donations or even sells it for a buck.

BOB GARFIELD: If I’m getting this right, you can write the anti-Harry Potter and go commercial with it. You cannot write the evolution of Harry Potter and do the same thing.

REBECCA TUSHNET: The more you are just continuing the story, the less likely a commercial version of that would be fair use. But, for example, there was a case some years back where a woman named Alice Randall wrote a book about “Gone with the Wind,” retelling the story with a half-sister of Scarlet O'Hara, who is the daughter of a slave, and basically told the story from an African-American perspective, revealing some of the hypocrisy and white supremacy encoded in the original. And a court found that that was likely to be fair use because of the way it commented on the original.

BOB GARFIELD: One of great literary events of 2012 was [LAUGHS] “Fifty Shades of Grey,” which is sort of kink erotica, that has its roots in?

REBECCA TUSHNET: It was originally a piece of “Twilight” fan fiction that has the basic “Twilight” structure, but doesn't actually copy any of the expression.

BOB GARFIELD: Some authors have been welcoming to fan fiction, Stephenie Meyer, the author of the “Twilight” Series being right at the top of the list. Others are kind of reactionary. The novelist Anne Rice has a very different view of her [LAUGHS] vampire fiction. Why do you think she's taken such a hard line?

REBECCA TUSHNET: There is a completely understandable feeling that other people get it wrong or that you’re very protective of your characters. The fact of the matter though is once they’re on the page, those characters start to live in other people's hearts too, and the only question is whether you'll find out about it, not whether it will happen.

BOB GARFIELD: We're talking about this as if it were some sort of novel phenomenon. In fact, the idea of derivative works goes back probably to all literature [LAUGHS] ever created by man?

REBECCA TUSHNET: Certainly. “The Odyssey” is a collection of stories that were told and retold, and each time the storyteller added his own particular spin on them. It goes on in every form of art – in painting, poetry, in music. It is, actually, the way that humans make stuff.

BOB GARFIELD: So then, where does the natural order of things that you’ve just described conflict with the legal and commercial infrastructures that keep the system, you know, running smoothly?

REBECCA TUSHNET: So I think the good news is that it doesn't have to conflict with the core copyright structure, which is valuable. You know, “The Avengers” is a movie that I like having in existence, and it's the kind that requires a big structure able to fund big productions. And that does require aggregating a bunch of little payments from movie tickets and DVDs, and so on. However, the commercial sector can never fully take over the realm of human production. And once we respect that, then we can live in pretty good harmony, I think.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, one final thing. You mentioned at the very outset that you came at this as - a fan, I'm just curious what a legal scholar is such a fan of, that she writes privately for her own amusement.

REBECCA TUSHNET: Well, gosh. I started as a kid with “Star Trek.” In law school, it was “The X-Files,” “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” “Smallville,” now this show on the CW called “Supernatural.” I am, I would say, at this point, a fan of fandom, in all its weirdness and all its wonderfulness.

BOB GARFIELD: Rebecca, thank you so much.

REBECCA TUSHNET: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Rebecca Tushnet is a law professor at Georgetown University and head of the legal committee for the Organization for Transformative Works.