BOB GARFIELD: With ad revenue and circulation continuing to decline for print newspapers, many are experimenting with… present and future business models for monetizing the newspaper industry.

[JINGLE]

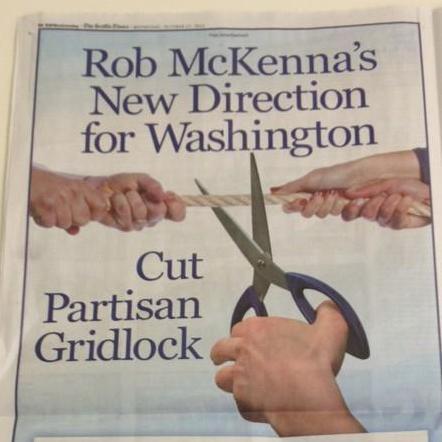

But earlier this month, the Seattle Times Company made the decision to gin up ad revenue by publishing political ads on its own dime, in its own pages. So, readers found a full-page ad depicting a hand holding scissors ready to cut the rope in a tug-of-war, with the caption, “Rob McKenna's New Direction for Washington. Cut Partisan Gridlock.” McKenna is the Republican candidate for governor in Washington. Readers also saw an ad supporting a referendum that would legalize gay marriage.

The ads cost the Times Company about $75,000 each, and both are part of a campaign by the Times Company to promote political advertising in newspapers, as in not on TV. The Times hoped to shield itself from charges of partisanship by promoting both a largely Democratic issue and a Republican candidate. Eli Sanders writes for the Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger. Eli, welcome to the show.

ELI SANDERS: Thanks for having me on.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, if I understand this right, the Seattle Times is doing this to demonstrate the power of newspapers in political advertising, a marketplace long since ceded to local TV. They want some of that revenue back, right?

ELI SANDERS: Yes, and I understand their frustration. It's true, the television stations in Seattle make millions of dollars from political advertising each campaigns season. And, as the Seattle Times is saying, they don’t. Yet, the TV stations largely piggyback on the work that the Seattle Times does, in terms of political coverage.

BOB GARFIELD: The Times Company made a point of seeming impartial in this experiment by buying one set of ads [LAUGHS] in its own paper for a Republican candidate and another set of ads in its paper for a ballot proposition more or less corresponding with the Democratic demographic. Do you think anyone has noticed that decision?

ELI SANDERS: No, it has largely failed as an argument here in Seattle and among the Times readership and people who follow the paper closely, not to mention among the newspaper’s stuff.

BOB GARFIELD: Tell me about the petition.

ELI SANDERS: The petition was generated by employees of the Seattle Times on the newsgathering side who were outraged about this and really demoralized, and they felt that they had to do something. And so, more than a hundred of them signed this letter to the publisher that says, you are hurting our credibility with this. This makes our job harder.

BOB GARFIELD: Strictly speaking, there’s nothing unethical or even irrational about this so-called experiment. It carries on a, a tradition of the owners of the newspaper behaving absolutely independently of the newsroom, and vice versa but from a public relations point of view?

ELI SANDERS: It's really a problem for their brand, and this is where I actually am not sure whether it's a rational business decision. There are three possible scenarios here. All of them are worrying. One is that the people who were running the company thought this was an incredibly smart business decision and did not foresee this backlash. Another is that they knew there would be a backlash but they were willing to risk it on the possibility that they would get more revenue from political ads. And another possibility is that the people at the company actually believed that they could prove what they are setting out to prove and then make more money this way.

BOB GARFIELD: Yeah, so let me ask you about the third possibility because this is not a scientific experiment [LAUGHS]. If McKenna wins and Referendum 74 wins, does that mean that newspapers are a superior medium for political advertising? If one prevails and the other does not, what have we learned?

ELI SANDERS: Exactly. I mean, this is a very high-risk gamble. What if both of them do lose? They have damaged their credibility and I don't know how they’re going to credibly argue that their print ads do anything.

BOB GARFIELD: Eli, the Seattle Times Company declined to appear on the program. However, one of its executives, Alan Fisco, did appear on the Seattle public radio station KUOW and had this to say:

[KUOW CLIP]:

ALAN FISCO: Our goal is hopefully to make sure that we get on the radar of those political strategists. And, and, frankly, we won't know whether this is successful until next year and in coming years, when we hope and expect that this will result in greater revenues to our newspaper.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: I, I believe that was the last public comment on the whole brouhaha. When erratic decisions are made, history shows that the ideas frequently began at the very, very top. I mean, here’s a scenario I can imagine. Frank Blethen, the owner and publisher, saying, here – here’s this great idea I have for building up the political category. See, we give away ads and then when these guys win, then, you know, then next cycle we just clean up. And the advertising manager goes, yeah – I don’t, I don’t know, Frank, there’s some risk attached to that. No, no, this is a great idea. Well, Frank, we’ve got our editorial independence to consider. No, no, no, this is – yeah, so –

[SANDERS LAUGHS]

So my question for you is does this have Blethen’s fingerprints all over it?

ELI SANDERS: [LAUGHS] You know, I don’t know, and this is part of the problem, that the Times Company’s lack of engagement with people who want to write about this now is allowing people like you and me to sit here and spin out scenarios where we’re talking in the voice of Frank Blethen. I have been doing the same thing. But they only say that this originated on the advertising side of the paper.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, it’s a weird one. On this week’s show this is the story that you can definitely brand the – you know, the three-headed goat.

[SANDERS LAUGHS]

Eli, thanks a lot.

ELI SANDERS: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Eli Sanders is an associate editor for the Seattle alt-weekly, The Stranger.