BOB GARFIELD: At the top of the hour, we heard Rebecca MacKinnon, an expert both on the Internet and the Far East, liken Facebookistan to China. Right now Facebook is blocked in China, but that hasn't prevented Facebook-like social media from surfacing. They've been made possible in part because of the protective anonymity of the Internet. Recently though, the Chinese government has taken Zuckerbergian steps to force users to register, making themselves known, if not to everyone, than at least to the government. Jeremy Goldkorn monitors Chinese media on his website danwei.com. He says Facebook and Twitter were blocked in China because of two tumultuous episodes in 2009.

JEREMY GOLDKORN: One was the demonstrations in Iran. People were talking about the demonstrations as being Facebook demonstrations and that spooked the Chinese government. And shortly after that, there was unrest in Sinjang in far western China between the Uyghur ethnic group and Han Chinese.

The Chinese government shut down the Internet completely in the province of Xinjiang for about six months, and after that everybody observing locally felt that there was no chance of Facebook and Twitter and YouTube being restored every again.

BOB GARFIELD: But, at the time there were fledgling domestic social media websites, and I guess they have vastly expanded. What are they?

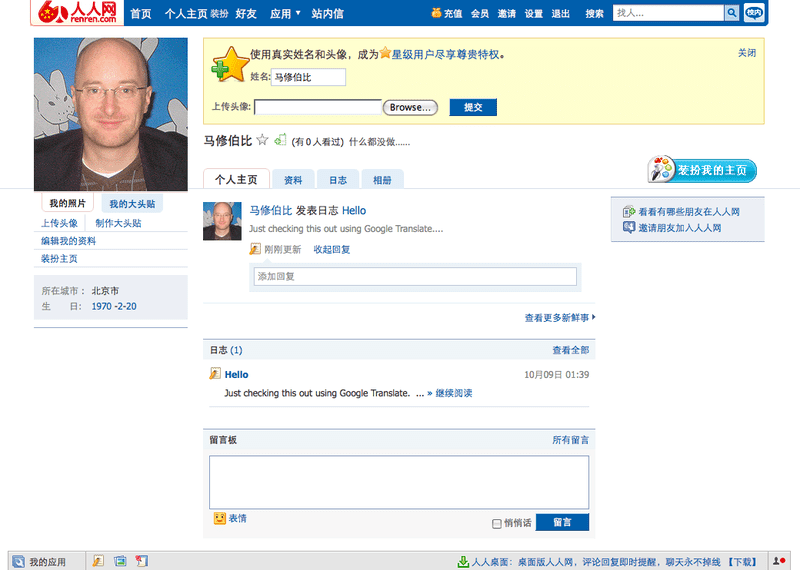

JEREMY GOLDKORN: Well, there are a few. The ones that most resemble Facebook are RenRen.com and Kaixin, which means happiness. RenRen started out very, very similar to Facebook. It was popular initially in schools. And, in fact, it used to be called a different name, which meant "on campus." And that's still the biggest Facebook-like website, with I think more than 100 million users. The other one is Kaixin which is notable for having first popularized the farming game before it was even popular in the West.

BOB GARFIELD: Kaixin is a knock-off of Facebook but FarmVille, which brings so much revenue [LAUGHS] into Facebook, is a knock-off of the game created by Kaixin's parent company.

JEREMY GOLDKORN: You know, this is one of the rare examples of the West completely ripping off a Chinese idea.

BOB GARFIELD: Meanwhile, there's a third big player.

JEREMY GOLDKORN: That's right. One can't ignore Weibo, often called the Twitter of China but is, in fact, quite a lot more complicated than Twitter and enables very easy photosharing, videosharing, threaded comments, games, groups, and is looking a lot more like Facebook than Twitter at the moment.

BOB GARFIELD: So if Facebook was blocked because it was a threat to the regime and to the Communist Party, what about these other sites? Domestic or not, they could stir up some trouble too.

JEREMY GOLDKORN: They are a channel for political discussion, and particular Weibo, but also the other two are websites where people communicate about a vast variety of topics, many of them quite threatening to the government. And the government is constantly monitoring them. In order to stay operating, they have to censor themselves. So all of them have vast teams of monitors who follow what's going on, on the websites and in real time will delete stuff that they think will get them into trouble. But a lot of stuff that young Chinese people never used to know about they now know about because their friends are re-posting little tidbits of news. So the government is doing their damnedest to slow this down, and I don't believe this is going to cause a revolution anytime soon. But it does mean that information is passing around more easily than it used to.

BOB GARFIELD: Jeremy, once again, thank you very much.

JEREMY GOLDKORN: Thank you for having me, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Jeremy Goldkorn is editor of danwei.com, a website that follows Chinese media.