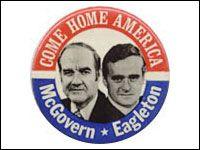

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mitt Romney’s choice of a running mate, due any day now, is hugely consequential to the campaign and seriously, seriously secret. One thing we do know, what the campaign wants to avoid above all else is surprises. Perhaps the rudest of those surprises, an enduring object lesson, came in 1972 when George McGovern picked a Missouri senator, Thomas Eagleton, to be his veep in the race against Richard Nixon. McGovern did virtually no background check, and the conversation in which he asked, and Eagleton accepted, took a mere 67 seconds.

THOMAS EAGLETON: Three minutes ago, George McGovern called and he said, “Tom, I've got a favor to ask of you,” and I said, “What's that?” He said, “I want you to be my running mate.” And I think I said something like, “I hastily accept” before he could retract and withdraw it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Clearly, McGovern didn’t know much about his running mate, and neither did the press, which was sent scrambling. In an interview we first ran in 2007, we spoke with reporter Clark Hoyt, who in 1972 was a cub reporter for the

Knight Ridder newspaper chain. He said that while he was reading up on the man who was to serve as the Democrat’s vice- presidential nominee for a mere 18 days, his lead fell into his lap.

CLARK HOYT: An anonymous caller called the Detroit Free Press, one of our newspapers, and asked to speak to John S. Knight, who was the founding father of Knight Newspapers. The operator connected the caller to John S. Knight III, his grandson, who was an editorial-writing intern at the Free Press.

The caller said that he knew that Senator Eagleton had suffered from depression and had been treated with electroshock therapy on more than one occasion. And this caller was sure that the Republicans would find this out and use it in some underhanded way during the political campaign, so the caller believed it should get out immediately.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What did you do with the tip?

CLARK HOYT: Well, even before I learned about the tip I went to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and I asked them if I could use their library and read all of their clips on Senator Eagleton. Newspaper clips in the old-fashioned envelopes are really quite revealing things, and what I saw were, in a very vivid, active public career, there would suddenly be gaps that would be unexplained. Sometimes there might be just a small paragraph that would say Senator Eagleton has been at the Mayo Clinic for a physical exam or Senator Eagleton has been exhausted and taking a rest, something like that. So there was already a red flag. When I got the tip, it had more credibility than it might have had otherwise.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So, once the facts lined up or at least the flags lined up, did you go to the campaign?

CLARK HOYT: No, I started looking for a doctor whose name we got from the tipster. And this doctor was no longer in practice, so it was quite difficult initially to locate the person. But I did and I — in a very nervous voice, I said, “I'm Clark Hoyt from Knight Newspapers in Washington, and I want to talk to you about the time in March of 1961 when Senator Eagleton was treated with electroshock therapy at Renard Hospital in St. Louis.” The doctor looked at me in horror, and as she slammed the door in my face, she said, “I can't talk to you about that.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And so, what happened after that?

CLARK HOYT: Well, Robert S. Boyd, my bureau chief, and I worked on this together. Then ultimately, we wound up with a two-page memo that we did take then to Senator McGovern's campaign. What we didn't know at the time was he already knew. We understand that the same tipster had called the McGovern campaign and told them the same information. What we were told is, “Senator Eagleton is on his way out here, you will have an interview with him. We're as determined as you are to get to the bottom of it.”

Within a day or so, we knew that we were being strung along. What they finally decided to do was to have an immediate press conference and have Senator Eagleton announce his mental health history.

[CLIP]:

THOMAS EAGLETON: On three occasions in my life, I have voluntarily gone into hospitals as a result of nervous exhaustion and fatigue. As a younger man, I must say that I drove myself too far.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, in answer to a question, he said part of his treatment was shock therapy.

CLARK HOYT: That's right, big news at that point. The campaign had sort of broken, in my view, an unwritten rule between reporters and campaigns, in the sense that we had a story and they simply announced it to the world. And so, in what they themselves referred to as a "consolation prize," they put us in a car, Bob Boyd and I, in a car with Senator Eagleton to drive from Custer back to Rapid City, South Dakota and the airport.

Senator Eagleton was sitting in the back seat. I was next to him, asking him questions all the way, to fill in the profile of him that I had originally been assigned to do. He was very gracious, answered every question, some quite uncomfortable questions. Throughout it, he chain smoked the entire time. He was perspiring profusely, and by the end of the ride I was soaking wet from him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you probably understood that that was the end of his vice-presidential ambitions and, and possibly the end of his political career. What did you think of the consequences of your actions, or did you at all?

CLARK HOYT: Yes, we thought a lot about the consequences of our actions, and Bob Boyd and I have talked about it a number of times, and we always felt that it was a story that was appropriately in the public domain. We don't know everything about Senator Eagleton's medical history. He never released any records. He never authorized his doctors to talk publicly about his case. But what we do know suggests that under great stress or at times right after great stress, he tended to shut down. And on at least two occasions he required hospitalization and the shock therapy.

And for someone who was aspiring to be vice-president of the United States, the proverbial heartbeat away from the presidency, I always felt that this was relevant information about his qualifications, his fitness, if you will, for the job. I don't see how we would have done it any differently.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Given what you learned about Thomas Eagleton, were you convinced he wouldn't have been a good vice-president?

CLARK HOYT: You know, that's a very good question. I am convinced that he was a very good senator, and he was reelected twice after that. He could have been reelected from Missouri as many times as he wanted to be. He was a very effective senator. He was one of the leaders in the War Powers Act in the Vietnam era.

In private life, afterward in St. Louis, he was a commanding figure in Missouri politics. He taught law at Washington University. He was obviously a man who had a very full and rich public career. He might have been a fine vice-president, but the question really is could he have been a good president. And I don't think we really know the answer to that because we don't really know what the nature of his condition was, whether it was all ancient history or whether under stress it might have been repeated again. We just don't know that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Clark, thank you very much.

CLARK HOYT: Brooke, thank you for asking me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Clark Hoyt who has recently served as the public editor of the New York Times and Robert Boyd won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for their Eagleton reporting.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

[1972 CLIP]:

THOMAS EAGLETON: Surely, I did not expect to stand before you tonight as the Democratic nominee for vice-president of the United States. I commit myself to the difficult task that lies ahead because I think all of the surprises of 1972 have shown us something very important. We’re learning to find opportunity in them, not just uncertainty and not just fear.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That's it for this week's show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Alex Goldman, PJ Vogt, Sarah Abdurrahman and Chris Neary, with more help from Amy DiPierro and Eliza Novick-Smith, and edited by me. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Andrew Dunne.

Katya Rogers is our senior producer. Ellen Horne is WNYC’s senior director of National Programs. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. Bob Garfield will be back next week. I’m Brooke Gladstone.