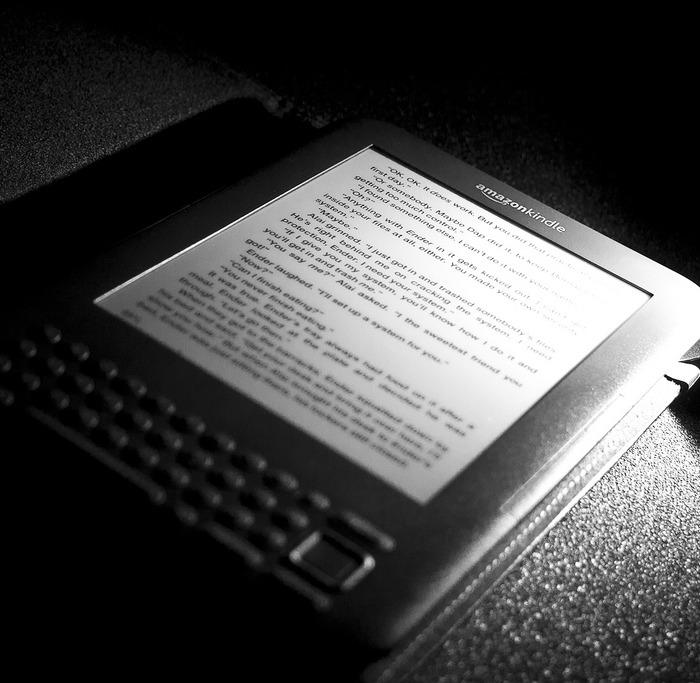

BOB GARFIELD: Last month, the Association of American Publishers announced a milestone: 2012 is the first year that adult e-books have outsold adult hardcover books. For the publishing industry, those e-books sales are especially valuable because they bring in not just revenue but data.

As you read from your Kindle, your Nook or your iPad, the device transmits all the details of how you do your reading, data that is beginning to shape the way books are written. Wall Street Journal reporter Alexandra Alter says that the new data is a big deal for an industry that has traditionally been unable to measure its audience.

ALEXANDRA ALTER: For them to be able to see most readers are skipping the introduction of this book, most readers are heavily underlining the third chapter of this book, that’s a pretty good indication of what is of interest to large groups of readers. They can use that to tailor books to people’s taste more.

Of course, not every book will be put through a focus group. I mean, you’re not gonna have Jonathan Franzen’s next novel cut in half because 30% of people didn’t finish Freedom, 25% of people didn’t finish The Corrections.

[BOB LAUGHS]

But I have talked to publishers who said, you know, they would like to have this kind of information. They wish Amazon would share it. Barnes & Noble intends to share some of it with publishers. So they’re looking forward to having a better sense of what readers like.

BOB GARFIELD: So that they can sell more of the same to the readers who clearly favor a certain genre, but also so that they can help authors fine tune manuscripts to make them more attractive to readers?

ALEXANDRA ALTER: Yes. A couple of publishers have already started releasing early digital editions of books, getting reader feedback on what they like and don’t like and then kind of tailoring the print edition to reflect those tastes and comments and all that feedback, so some of that is happening already, mostly with some of your new more digitally savvy publishers.

BOB GARFIELD: And would the data be able to tell what editors have long since been dependent on to decide whether it takes too long to get to the plot, whether it bogs down around page 150? Will data begin to usurp the functions of live human beings?

ALEXANDRA ALTER: I think you will always need editors, but I think it will clarify some of those assumptions. I mean, publishing has always been kind of an instinct-driven business. It’s – of course, it’s staffed with English majors, not number crunchers. And a lot of the decisions about what books to acquire, how to edit them, what length they should be, those are made by people who love books.

So you’ll certainly, I think, have those people weighing in and making those choices, but they might take into account if, you know, most readers quit the book halfway through, or you can even tell if somebody puts the book, you know, down a few times. So if the reader gets to the end and they suddenly decide they’re gonna stop reading that and read another book for two weeks and then come back and maybe they’ll see how it ends, you could probably deduce that that wasn’t dramatic enough.

BOB GARFIELD: Mm. So there’re two nightmare scenarios. One is the privacy one, which we’ll get to in a moment. But the other is taking the human element out of fiction. Now, I understand Jonathan Franzen is at no risk, but I can certainly see publishers, if once they get a hold of this information, bringing this data to bear on genre authors. And what gets lost in the process potentially seems to me is the author’s voice. If everything gets informed by data, do we lose something fundamental about literature?

ALEXANDRA ALTER: That could be a risk. On the other hand, if you look at the bestseller list and what’s popular, it’s pretty diverse. Hilary Mantel’s Tudor drama, Bring Up the Bodies, the sequel to Wolf Hall, is on the bestseller list. So are a bunch of crime fiction novels. So is The Hunger Games. Publishers have always catered to a variety of tastes.

BOB GARFIELD: You know, actually, I thought you were gonna give me a different answer. I thought you were going to say, if you look at the bestseller lists, it’s always pre-crappy for your convenience. [LAUGHS]

ALEXANDRA ALTER: [LAUGHS]

BOB GARFIELD: James Patterson is formulaic enough. He’s not gonna get any help from an algorithm.

ALEXANDRA ALTER: Well, that – I – that could be true, as well. But you do see a range occasionally popping up.

BOB GARFIELD: Let’s get, finally, to the privacy issue. What if a law enforcement agency went to Amazon and said, we’d like to see what Alexandra Alter has been reading the last six months, where she started, where she stopped, what she highlighted because, you know, we’re just suspicious about this woman?

ALEXANDRA ALTER: That’s definitely a concern. In fact, a couple of organizations, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, have raised this issue. And they managed to pass a law in California earlier this year called the Reader Privacy Act, which requires that law enforcement agencies get a court order before they can demand this kind of information.

But it’s certainly a risk that kind of information could definitely be pulled, if you were under suspicion for something. It could require that those companies turn over your individual reading habits.

BOB GARFIELD: I guess the question is does the availability of this technology and the subpoena ability of it put us all in danger of being in suspicion over something just on the basis of what we’re reading, you know, in the privacy of our own Kindles?

ALEXANDRA ALTER: I don’t believe it would. I think this kind of information would be pulled by law enforcement if you were already under suspicion for something, if you were a suspect. I don’t think they’re combing through it to see what people are reading. That would take forever, and they would have no basis for going to the companies to get that information.

So I don’t think it’s the kind of thing where like the cell phone calls are being tracked extensively. Certainly, Internet searches are probably looked at. But I don’t think that law enforcement is going through people’s digital reading habits. I think it would be basically a waste of their time, at this point.

BOB GARFIELD: Alexandra, thank you very much.

ALEXANDRA ALTER: Thanks so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

BOB GARFIELD: Alexandra Alter covers books and culture for the Wall Street Journal.