BROOKE GLADSTONE: Last year more journalists died covering political unrest than any year on record, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Two of them covering the Libyan uprising were seasoned war photographers Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington. Among Hetherington’s many assignments, he had recently spent much of a year embedded with a platoon of U.S. soldiers deployed to a remote, very dangerous outpost in Afghanistan, an assignment he shared with fellow conflict reporter and friend, Sebastian Junger.

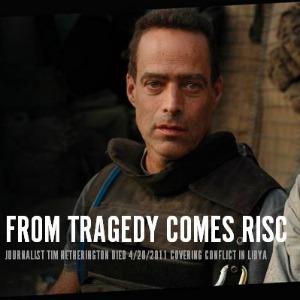

When Junger learned that Hetherington’s mortal injury could have been treated, he marked the anniversary of his and Hondros’ death by founding a new organization called Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues, or RISC, to train freelance reporters in life saving. Its first session took place last week in New York. Sebastian, welcome back to the show.

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Thank you very much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So first, tell me what you thought happened to Tim Hetherington a year ago and what you learned since.

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: What I was told is that a mortar fired by Gaddafi forces exploded in the midst of a group of rebel fighters and journalists, and Chris Hondros was hit in the head by shrapnel and rendered unconscious immediately, and it was a mortal wound. Tim was hit in the groin and so he was fully conscious, but he was losing a lot of blood. And over the course of the next ten minutes or so he lost so much blood that he died in the back of a pickup truck as they were – the rebels were racing him back towards a hospital to be treated.

And I sort of assumed that an arterial bleed in the groin is, you know, basically a death sentence but a combat medic told me that not necessarily. There are things you can do to slow down the blood loss, even in a situation like that, and all they had to do was prolong his life by five minutes, just to get him to the hospital and that maybe if the journalists around him had known some battlefield medicine, that they might have been able to keep him alive.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You knew him incredibly well. What kind of training did he have?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Oh, none. Nobody does. I mean, no freelancers do.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You? Did you have any?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: No. I mean, I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I don’t know anyone who’s had any formal medical training. I mean, I think the insurance companies require that the media organizations train the people they have who are on salary, but freelancers no. And so I know this from when I was in the field; we all have a kind of slightly fatalistic attitude, like okay, well, if it happens it happens, but meanwhile, let’s go get the story. And I just thought I needed to start a nonprofit that would train freelancers for free.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How do you pay for that?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Well initially I went to the news organizations that Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington worked for, to Vanity Fair, Condé Nast, to CNN, to Getty, to the Chris Hondros Foundation established by his fiancé, to National Geographic and ABC News. And they donated very generously and we were able to do the first training program. Now we’re going after real corporate money.

We want to try to bring the program to the freelancers just to alleviate the travel costs for them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: War reporting seems to have shifted towards freelancers, hasn’t it?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Well, the economics of it are a little bit more favorable for the news organizations. You're not paying someone’s salary, you're not paying their insurance. You're really not responsible for them. You’re buying their work product, which is a great deal for the news organizations and, frankly, it’s a great deal for the freelancers, as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: The looseness of it allows anyone who is motivated and ambitious and courageous and has a good camera to simply go to Libya during the war, hook up with the rebels, take images and hope to sell them. And that’s a real shortcut compared to the kind of career ladder you have to climb if you're just grinding your way through a salaried version of all that. That’s a lifelong process. This you can do in six months.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So what’s the balance that needs to be struck so that freelancers can be safer and yet news organizations can afford to hire them?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: I think what news organizations might do is strongly encourage freelancers to get health insurance, life insurance, a bulletproof vest and a helmet and to have medical equipment, and to be properly trained in battlefield medicine.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You said “encourage freelancers” to do that, not require them to do that or not pay for them to do that.

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: I think it’s a matter of the culture.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Not just the culture at a professional news organization that wants to save money on insurance, but the culture of the young, cocky war reporter that believes in his or her own invulnerability.

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: You’re not gonna change the cockiness of youth. That’s thousands of years old, and thank God it’s there. But what I would say is that 20 years ago this wasn’t true but now having a bulletproof vest and a helmet is a mark of professionalism. And you show up on a battlefield without any of that gear and you just look like a jerk.

Every freelancer wants to look professional, and if the culture of freelance journalism starts to move away from that sort of cavalier fatalism towards – listen, we should all be trained so that God forbid one of us gets hit we all know what to do, it’s a kind of caretaking thing. And at least two of the people who were in the program – there were 24 students – two of them had already been wounded on the battlefield. They’re way more mature than I was in my early thirties when I first went off to do this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So best case scenario?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: The best case scenario for me is that – I mean, there’s gonna be another Tim and maybe that person will be saved by someone who we’ve instructed, and then his friends or her friends and family don’t go through what we all went through when Tim died and Chris died.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Other than creating RISC, what impact did Tim’s death have on your work?

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Me making a decision not to cover combat anymore. I didn’t want to put the people I care about through the experience that he had put me through. I’m 50 years old. I feel like one of the duties of being a fully mature person is to not inflict pain on people you love. And that’s not quite true at, at 30 but at 50 it starts to be pretty true. And I just – I wanted to make sure I never did that.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sebastian, thank you very much.

SEBASTIAN JUNGER: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sebastian Junger is author, most recently, of War. He co-directed “Restrepo” with Tim Hetherington, and he’s just founded RISC, Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues, which we’ll link on our web site.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP AND UNDER]