BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Super Tuesday was so last week! And like all the other traditional benchmarks of 2012’s presidential season, Super Tuesday, like Iowa, like New Hampshire, was – meh. Call it “Meh Tuesday” partly because fewer than half the states participated, as did in 2008, but mostly because, despite the breathless expostulations of pundits, it resolved nothing.

WOMAN: And so, if you look at that and you say, okay, what’s Romney’s problem.

[SOUND OF PEOPLE RESPONDING]

Well, he’s not connecting. He’s not even connecting to the people he should be connecting to…

MAN: Now, this is gas clearly labeled, but if Republicans get to their convention with no nominee, I predict they’ll pick someone other than those in the current field.

MAN: And in the battleground state of Ohio, he will able to secure his claim to the nomination only if he beats Rick Santorum in that big state.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That last prediction was simply wrong. The previous one was meaningless, and the first one sounded like a little cry of pain modified to fit your screen.

BOB GARFIELD: Typically, political pundits are able to get away with making predictions that are spectacularly wrong because there’s no real downside to it. Make an extraordinary claim and you’ll get a ton of attention. If, a few years later, it turns out you were wrong, well it’s not as if somebody’s gonna go back and check your work. That is, until now. Sanjay Ayer is one of the minds behind PunditTracker, a new site that will keep track of the predictions that pundits make and score whether or not they actually turn out to be – you know, true.

SANJAY AYER: One of the big problems is the scoring systems. The traditional approach to evaluating pundits uses what we call a hit rate or batting average approach. So let’s say you make ten calls and you get eight of them right, you have an 80 percent hit rate. Right? That sounds great, but the problem is it’s really meaningless without context. And that’s really the crux of our scoring system, is we will factor in how bold a call is. So the person who predicts the financial crisis will get more credit than me who predicts, you know, the sun will rise tomorrow.

BOB GARFIELD: So how far have you gotten on this?

SANJAY AYER: We’re running the site as a blog right now. The full launch is scheduled for the springtime, but we’ve put a couple of content pieces up there already. One of them is a sports analysis where we analyze the football picks from all the pundits from ESPN and Yahoo! and CBS. That study showed that the results were decidedly mediocre.

Actually, the users of those websites, by and large, outperformed the experts. And that really corroborates a lot of the work that’s been done in this industry in the past, but there are counter examples. We did a study on finance, looking at Barron’s – it’s a financial periodical. And they do an event every year where they bring in a group of experts and ask them to make their stock picks for the following year. And looking at that track record, it was actually quite good.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, so far, Sanjay, you’ve given us stock market calls and sporting predictions. But, for obvious reasons, political predictions tend not to be so black and white. How do you account for that in coming up with your algorithm or whatever it is that you bring to bear [LAUGHS] on this problem?

SANJAY AYER: So there’s two ways we can go about kind of addressing that issue. One is filter the calls on the front end. So if a call is too vague to score or the pundit’s hedging too much, we just won’t put that call on the site. But the second way, and I think the more interesting way, is to make our algorithm flexible enough so if they make a call that something could happen or is likely to happen, we can give them partial credit if they’re right. And with the hedge-a-call we can give ‘em partial credit, as well.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, all of this presupposes that the function of pundits is to provide actual insight and to accurately predict the future. I would assert they’re just there for dramatic tension and confrontation, so that viewers can watch to have their world views either validated or to have a fight picked.

SANJAY AYER: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BOB GARFIELD: Does it matter, ultimately, to CNN or FOX News Channel if their pundits are right or wrong?

SANJAY AYER: To the extent that networks are just trying to maximize ratings, extreme viewpoints will sell better than nuanced viewpoints, right? But if you can provide users with some sort of informational metric that evaluates how good a pundit is, it allows them to maybe cut through some of that media filter.

You know, I was just watching a financial show a couple of weeks ago and they were interviewing a pundit who we have looked at the data and his results are frankly terrible. What they did when they introduced him was cherry pick the two calls he got right and introduced him as an expert. If we can provide data that cuts through all those filters and biases, we think in the end the public will have demand for it.

BOB GARFIELD: Let’s just say the world of cable news is not quite as cynical as I asserted, do you think they are responsible for vetting the records of pundits?

SANJAY AYER: I think they have some responsibility, but the problem is the only time people refer back to old news, which includes past predictions, is when there’s a trigger. And that trigger is typically an event. So we’ll go back, we’ll look through the archives. Some people are bound to have predicted everything. And so, we’ll elevate that person to oracle status, you know, at least temporarily.

But the problem is on the flip side, a non-event is non-news, so there’s no corresponding search when a prediction doesn’t happen for the pundits who made those failed predictions. It’s an inherent skew that’s more prone to uncovering hits than misses. And it gives us, the public, kind of a warped sense of how accurate pundits are.

BOB GARFIELD: One final thing, Sanjay. The – the ascendancy of fact checking has really brought a whole new level of vetting to political advertising and debate claims, and so on, but hasn’t seemed to chasten politicians any. They’ve just figured out a sort of new way to lie. Do you think ultimately that you are going to have a material effect on the prognostication game?

SANJAY AYER: If we can really get the data right and convey that to consumers, there’ll be a natural weeding out. You know, if a pundit is showing up on TV, you know, say we do a grade score, and he’s got a D, over time we think that’ll start to whittle away at his credibility and people will at least pay more attention to how his calls turn out, or not.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, but two cautionary words for you, ready?

SANJAY AYER: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

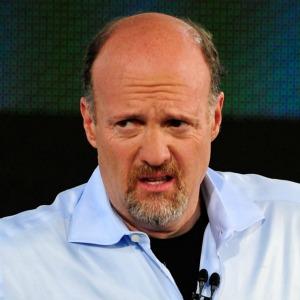

BOB GARFIELD: Jim Cramer.

SANJAY AYER: [LAUGHS] He will be one of the first pundits we will track. Let’s put it that way.

BOB GARFIELD: Sanjay, thanks so much.

SANJAY AYER: Thanks so much, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Sanjay Ayer is the founder and CEO of PunditTracker.