Life in Facebookistan

BOB GARFIELD:

From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

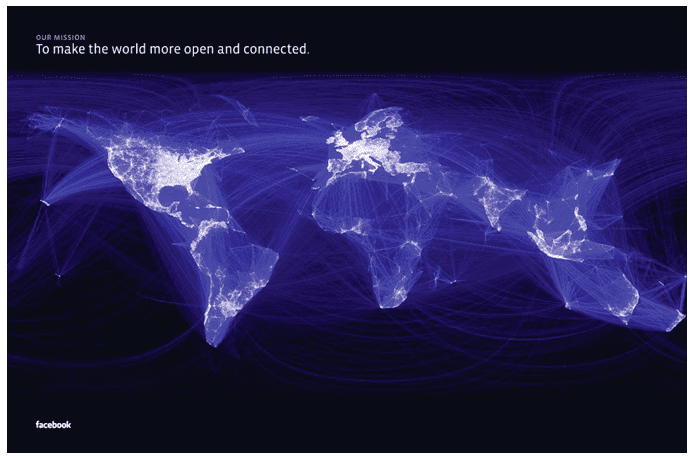

And I'm Brooke Gladstone. If you're listening to the show on your radio, odds are you reside in the United States, population 312 million. And odds are increasing you live in another country, as well, population 845 million, soon to reach a billion.

REBECCA MacKINNON:

Which makes it the third largest country on the planet, after China and India.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

That's Rebecca MacKinnon. In her book, Consent, the Network, she labels this burgeoning world power Facebookistan.

REBECCA MacKINNON:

Facebookistan, it's run by a sovereign who believes himself to be benevolent.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

She means Mark Zuckerberg, who founded it in 2004. But we're not going to spend much on history.

REBECCA MacKINNON:

Maybe you saw the movie The Social Network?

[CLIP]:

JESSE EISENBERG AS MARK ZUCKERBERG:

This is what drives life in college: are you having sex or aren't you? It's why people take certain classes and sit where they sit, do what they do...some center. You know, that's what TheFacebook is gonna be about. People are gonna log on because after all the cake and watermelon there's a chance they're actually gonna get laid, meet a girl.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

It portrays Zuckerberg as a lonely nerd whose billion-dollar brainchild was the result of displacement, a compensation for loneliness, our ultimate revenge fantasy.

MARK ZUCKERBERG:

Well, the reality for people that know me is I've actually been dating the same girl since before I started Facebook, so obviously that's not part of it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Mark Zuckerberg.

MARK ZUCKERBERG:

They just can't wrap their head around the idea that someone might build something because they like building things.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

On Wednesday, Zuckerberg filed for his eagerly awaited initial public offering of stock, to raise some five to ten billion dollars. It's he tech world's biggest ever. So we're devoting this hour to this "thing" that Mark built, this place, where people share photos, links and passions, advocate, organize, network, lurk, confide, sell and spy. And they do unto others, so Facebookistan does unto them.

But Facebookistan is not compelled to abide by the rules it sets for its citizens. In fact, this could be Facebookistan's national anthem.

[CLIP/DON AND JUAN SINGING WHAT'S YOUR NAME UP AND UNDER]

Rebecca MacKinnon.

REBECCA MacKINNON:

Part of Facebook's ideology is that people should be up front and transparent about who they are. The management team is setting rules — we know them as, as terms of service but they're a kind of law in this digital realm, a set of rules, for instance, around identity. So Facebook requires that you use your real name when you sign onto an account. If you violate the terms of service, of course, you can get kicked out.

MAN:

We got people through this really big hurdle of wanting to put up their full name, a real picture, mobile phone number, you know, in a ton of cases.

REBECCA MacKINNON:

It's a very paternalistic attitude that's quite similar to what I've experienced in my time in China, which is the government telling people, you know, we know what's best for you, our economy is growing, and your life is getting better.

MAN:

We decided that these would be the social norms now, and we — we just went for it.

DON AND JUAN/SINGING:

Shooby-doo-bop-bah-dah!

BOB GARFIELD:

Facebook, as we heard repeatedly through the Arab Spring, is having an increasingly powerful impact in the physical world, where it's being used by dissidents to organize against autocratic regimes. Wael Ghoneim, a young Google marketing exec based in Cairo, famously used a Facebook page to mobilize thousands to go into the streets almost exactly a year ago.

And before that, says Jillian York, of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, there was Tunisia.

JILLIAN YORK:

A number of video-sharing sites were blocked, and so people in Tunisia were instead using Facebook video-sharing capabilities to share news and get it out of the country. And the same with Syria, Facebook was actually unblocked by the Syrian government about February 2011 in an effort to try to surveil activists. But at the same time, Syrians have persevered, have been — continued to use Facebook as a news source, despite government efforts to use it to entrap activists.

BOB GARFIELD:

But sometimes Facebook may have put users at risk. At the beginning of Iran's Green Movement, Facebook, encouraged dissidents to form groups on the site. But a sudden classical Facebookian change in the rules in December 2009 led to once-private information suddenly becoming public. Names, profile photos, favorite causes and lists of friends were there for the taking.

After an outcry, users won some privacy back. The EFF's Jillian York says that in Egypt Facebook's rules may have put a whole movement at risk.

JILLIAN YORK:

In November 2010 they took down the famous "We are all Khaled Said" page from Egypt because Wael Ghoneim was using a pseudonym. You know, someone from an NGO, actually, intervened. Had that not happened, we may never have seen the Egyptian revolution as we saw it.

Facebook says its policy is because they want to create a culture of trust and real names, but that's a foreign example of a case where they're not really thinking beyond U.S. borders.

BOB GARFIELD:

This is a website that began as a way for college kids to, you know, check out the relative hotness of other undergrads. [LAUGHS] And it has evolved into this vast social sharing site. Do you believe that Mark Zuckerberg and his colleagues have a responsibility to adapt Facebook to accommodate its more life and death applications?

JILLIAN YORK:

You know, whether Facebook likes it or not, and — and my suspicion is that they don't like it so much, they've downplayed it — Facebook has become a haven for activists. It's very well set up for that. It's, it's very easy to attract other people to whatever cause you're trying to promote. And so, in that sense, yes, I do think that Facebook has a responsibility to their users.

BOB GARFIELD:

Responsibility, we know from Spiderman, is the obligation that accompanies great power. And that's where Facebook runs into PR problems, mostly over its use of your personal information. Facebook tends to change its privacy rules abruptly and unilaterally. You may wake up to discover that information you thought you were sharing with friends has become accessible to everybody, and especially advertisers. If there is sufficient outcry, Facebook will retrench and retool, with apologies.

For instance, initially, it was impossible to delete your Facebook profile. After users complained, Facebook adjusted its settings so that now it's just really hard.

More recently the site has been blasted for tracking users as they browse outside websites and for holding data on Web users who are not even Facebook members.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

A few users may get the heebie-jeebies, but Clay Shirky, author of Cognitive Surplus, says Facebook has nothing to fear.

CLAY SHIRKY:

They have now achieved not just the largest user base in the history of the Internet, they have a majority of their potential user base already on the server.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

And who is that potential user base?

CLAY SHIRKY:

Well, it's everybody who's got an Internet connection and doesn't live in China.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

But there are so many drawbacks, at least I feel them. The interface is a pain.

CLAY SHIRKY:

So do you remember the interface for Napster? That thing was a — a, a throggo [?] —

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

— of bad interface design. The — the user interface for Napster was a nightmare! The user experience for Napster was uncompetably better than anything that had ever been offered because Napster gave people access to an underlying resource that they wanted. I can have the best interface in the world for a social network, but if it's not sitting on top of the sociograph of 700 million people, I get — I get nothing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

It's designed to take data from you and seems to put obstacles, even as they proclaim the opposite, to controlling your data effectively. I found it an unpleasant environment. Isn't there, at least in some quarters, a rising cry of people like me?

CLAY SHIRKY:

[LAUGHS] There is a rising cry of people like me, and — and essentially what's happened is that the hipsters and eggheads who always hate popular things —

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

— now hate Facebook. I've been using the network 20 years now. I remember when we believed, wrongly, in the 1990s that because the Internet was spreading, the population would become more geeky. We had to be geeks to understand how the thing worked in order to be able to use it.

What we didn't understand is there is no such thing as a "mass geek population" [LAUGHS] that, in fact, what's happened with the Internet spread is that it's just become easy enough to use that nobody has to have any idea how it works. So while there are people who dislike the interface, there are people who dislike the data lock-in, there are people who dislike the privacy ramifications, that group have become such a tiny subset of the user base that not only could Facebook lose all of us —

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

— and, and — and barely break its stride, it might actually make their lives easier if we all left.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS] So when you say "people like me" you were including yourself [LAUGHS] in this group of criers.

CLAY SHIRKY:

Ab — absolutely. I, I have the same concerns. My — my friend Anil Dash wrote a wonderful piece called "Facebook is Gaslighting the Web," in which Facebook is just getting people used to the idea that there's a higher and higher degree of either control or observation around data that ordinary people might be willing to show anybody. And that change has been taking place over years.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Facebook is propagating the notion that we don't care and, therefore, eventually we just won't care?

CLAY SHIRKY:

Right. With continual revisions to their privacy policy, continual revisions to what material is presumptively exposed or hidden, they've been changing the environment to alter our assumptions from "It's my data, I put it up someplace, people can see it or not see it, based on controls I set" to the idea that the Facebook defaults and the Facebook log-in become the new normal for most of the Internet using population.

MARK ZUCKERBERG:

We decided that these would be the social norms now, and we — we just went for it —

[SOUND ECHOING]:

Just went for it, just went for it, just went for it, just went for it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Can't the market fix this? Why can't you just go elsewhere? Shirkey says go ahead, launch a competing service. He guarantees no one will join.

CLAY SHIRKY:

We are moving towards a world where Facebook is almost undisciplinable by the market. If Facebook has no competition, then the only regulatory bodies we can imagine are the world's governments. So now the right to privacy legislation in Europe is moving along. It may be that the thing that keeps Facebook from going all the way in the direction of simply stripmining its users personal data is the regulatory environment, like the phone company. As my friend Dana Boyd said, Facebook is a utility, meaning its become essentially something you have to have in your life simply to get along, but utilities get regulated.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Clay Shirkey, author of Cognitive Surplus. He will be the first to tell you that Zuckerberg's realm, despite its problems, is a mighty enticing place.