BROOKE GLADSTONE:

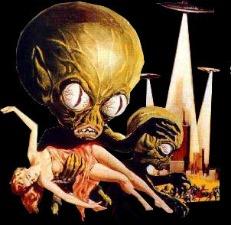

Some predict that a little over a year from now on the numerically chilling 12/21/2012 the world will end. I mean, the end does have to come sometime, right? And if there are still journalists, they'll need a plan for how to report our last days.

A recent journalism pow-wow attended by heavy hitters like Google, The New York Times and the Knight Foundation featured freewheeling discussions of things like "present and future business models to monetize the newspaper industry" and so on.

But the loosely-scheduled so-called un-conference also featured a white board, where anyone could pose a topic. And Andrew Fitzgerald, a content and program manager for Twitter, suggested a session on reporting the apocalypse. The group settled on two scenarios: alien invasion and global pandemic. Fitzgerald says he had an epiphany after all that talk about the future of the news.

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

I was standing there looking at the white board myself, and I thought, but what about the real future.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

What about the end of time? And so, just walked up to the white board myself and put down, "reporting the end of the world." And we sat there and discussed best practices and tips and tricks -

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- for reporting during the apocalypse.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

You wrote in your blog post, "You wake up on a Tuesday, make yourself some coffee, open your laptop, check Twitter to find space ships are suspended over our planet's major cities preparing to attack." So how did you think things would play out from there?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

Well, we borrowed the scenario, admittedly, from Independence Day, which I am a secret fan of.

[CLIP]:

BILL PULLMAN AS PRESIDENT WHITMORE:

And you will once again be fighting for our freedom, not from tyranny, oppression or persecution but from annihilation. And should we win the day, the Fourth of July will no longer be known as an American holiday but as the day when the world declared in one voice, "We will not go quietly into the night. We will not vanish without a fight!"

[END CLIP]

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

That model of the aliens appear, there is a short period of time before they begin any sort of action, and so you have a period of time of spreading information in which our communications infrastructures are still working.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

A lot of the technology is going to be the first thing to go - no Internet, maybe no phone communications, or at least cell phones. So how do you even begin as a journalist to get the information out?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

Right. The first thing Zlorg, the alien lord, wants to do is eliminate human ability to communicate. We are incredibly reliant on the technologies that we use on a daily basis. We are not very prepared for those technologies to not be there.

Human communication has this rich history of different formats, everything from carrier pigeons to smoke signals, to ham radio, but we don't have a lot of experience in, say, ham radios, which is the format we decided would be probably the best one to use. You can — you could probably fit a tweet around a pigeon's leg.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So [LAUGHS], but seriously, how are you a journalist in the classic sense during an alien invasion? What would you cover?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

When the aliens invade, the first thing that you need to do is do some service journalism. Report where they're moving, what they're up to. You need to explain alien anatomy, such that people know that what looks like an alien's hand is actually its mouth, and so you don't want to move your delicious human guts anywhere near that appendage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So what was the reaction among your journalism cohorts when someone raised the idea that perhaps journalists ought to engage in getting the aliens' side of things?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

There was a fair amount of shouting down.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

First we talked about which celebrity journalist would be first —

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

- to interview Zlorg, the alien lord, full well knowing that there was a high percentage chance of them not surviving the interview.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Geraldo Rivera! [LAUGHS]

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

Uh, no names, no names.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Very quickly we started talking about the political reporting on people who thought we should listen to aliens verses people who didn't think we should start listening to the aliens.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Did it break down along party lines?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

I believe the phrase was "Alien-Hugging Democrats vs. Alien-Killing Republicans."

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS] Now, you note that David Carr, the media columnist for The New York Times, observed at the un-conference that in conflict journalism, it's the symmetries of war that keep journalists safe and that there's no symmetry in our war with our would-be destroyers. What does that mean?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

The fact that these two sides are warriors battling with one another, as a journalist you are in a separate role that is not a part of that symmetrical relationship. And so, it is the battle between these two sides that protects you. Unfortunately, in alien conflict it is the ultimate asymmetry in warfare, the ultimate other.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Well, every single war ever fought has involved the home team and the other, with a capital "O." That's why war after war you always hear about "the other" killing babies. Most of these stories are made up, but they keep reappearing so that they seem less than human; they don't value life the way that we do.

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

And maybe we would learn this in the sit-down one-on-one with Zlorg, in which we talk about, you know, his upbringing. Maybe they value life more, and maybe they have a, a reason why humanity must be eradicated that we should listen to.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Let's go to the global pandemic scenario. You wrote, "The aliens left us miraculously alone, disappeared into the far reaches of space, and everyone won Pulitzers for their coverage of Invasion Watch 2012." But then you wake up on a Tuesday - Tuesday seems to be a bad day in your scenarios - make yourself some coffee, open your laptop and check Twitter, to see reports of a fast- moving, fatal illness sweeping the planet. And the big discussion around the possible pandemic was whether it'd be okay to suspend the facts. What did you mean by that?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

I wanted to raise the question of whether or not one should not wait for verification and put information out there and give it a rating, say, we don't really believe this is true, we give it a 3 on our pandemic watch truth scale. The journalists in the room roundly disagreed with this idea. Every one raised the point that, actually, in these disaster scenarios facts are even more important.

The example that really resonated with a lot of people in the room was Katrina. The rumors that propagated during those first couple of days, many of which turned out to be absolutely untrue, were widely reported in — in mass media. We decided that that for journalists in a time of apocalypse, the facts are actually even more important.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So you considered the world ending in alien invasion and the world ending in a pandemic. I'm surprised you didn't consider a scenario which many futurists believe in, that the robots will eventually take over.

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

[LAUGHS] It was our planned third apocalypse to go through.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

[LAUGHS] So let's say it really happened, as some believe it will in a little more than a year, which would you prefer, to be devoured by aliens or killed in a global pandemic?

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

You know, I think I would probably choose alien invasion, if for no other reason than at the very end to know that we weren't alone in the universe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Good answer. Thank you, Andrew.

ANDREW FITZGERALD:

Thank you so much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Andrew Fitzgerald is a content and program manager for Twitter.