BROOKE GLADSTONE:

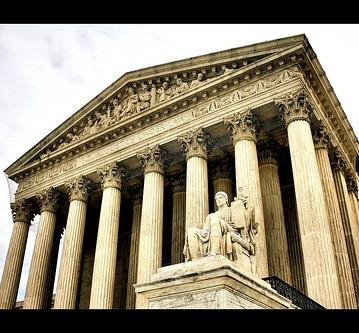

On October 3rd. the Supreme Court convened its latest term. And, as usual, there are cases that concern matters of surveillance, free speech, copyright, you know, stuff we’d like to talk about on the show.

Adam Liptak covers the Court for The New York Times and he says he’s looking forward to the case called the FCC vs. FOX Television, which could effectively stop the FCC from regulating content on broadcast TV.

ADAM LIPTAK:

It’s such a great case. You know, the Court has in recent years been very engaged with the First Amendment. Now they have a chance to look at a really big question they haven’t fully engaged since 1978, when George Carlin went on the radio with a very funny but very filthy monologue.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

The famous “Seven Dirty Words,” and that was on a Pacifica station.

ADAM LIPTAK:

Exactly. And back then the Court said that broadcast is uniquely pervasive and can kind of ambush children and, therefore, the government can regulate broadcast.

This new case involving some swearing on awards shows and some bare buttocks on NYPD Blue raises the question of whether we still live in that world where broadcast TV, as opposed to cable TV, is uniquely pervasive, because broadcast stations are regulated and everything else is not. The government makes the argument that there are still some small number of people who still get their TV over the air, and those people may seek out solely broadcast as opposed to cable television stations because they want a safe harbor from the depravity of, of everything else that goes on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Let’s shift gears to United States vs. Jones. It’s up to the Supreme Court to decide whether the government can track a suspect via GPS without a warrant.

ADAM LIPTAK:

The case asks the question of whether the government or the police can sneak up to your car, put their own device on it and collect a ton of information about you, whether you go to the liquor store, whether you go to the church, whether you visit perhaps a girlfriend.

The Federal Appeals Court in Washington said that was just too much information, that that crossed a Fourth Amendment line. And the government says that you don’t need a warrant, that all this device does is sort of enhances that thing police have always done, which is stake out my car, follow my car around in their squad car; nobody thinks that’s a problem.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Okay, but this particular law that’s being challenged has a guy named Antoine Jones as its poster child, not a very attractive character.

ADAM LIPTAK:

Antoine Jones was, before his conviction was overturned, sentenced to life in prison for dealing in cocaine. This data allowed the police to track Mr. Jones’ movements, including to a place where he kept his cocaine. It’s not typically the good guys whose cases reach the courts, but these principles are meant to be neutral principles that govern good guys and bad guys too.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Where do you think the Supreme Court will rule?

ADAM LIPTAK:

The notion that some collection of information is okay, but there’s a moment at which it becomes too much is a very hard line for them to draw. So several of the signs point in the direction of the Supreme Court saying, well maybe this is okay, but we might come back at this and there may be some stuff that’s no good.

It’s also possible that the Court focuses on the very narrow question of whether the police should be allowed to put something on your property. And that kind of property rights argument could conceivably appeal to some of the more conservative justices, on the one hand, while the more liberal justices concerned about privacy might join up in them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Hmm!

ADAM LIPTAK:

So it may be that you get a ruling that you can track all you like but you can’t be sticking stuff on my car.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Let’s talk now about Golan v. Holder, which is an argument against a law that was passed in 1994 that shrank the public domain. Basically it took foreign cultural properties that were in the public domain out, in order to put the United States in compliance with an international convention. This really upset filmmakers, conductors, people who use raw material in the public domain to make their own work.

ADAM LIPTAK:

The case was argued the other day, and it was clear from the argument that the justices understood that materials that are in the public domain that people rely on to perform symphonies and make other kinds of derivative works, to withdraw those from the public domain is a fairly bold step.

At the same time, it’s important to say that all this international convention did was restore copyrights to works that were, for various reasons, unable to be copyrighted in the first place. It didn’t extend the copyright they would have been entitled to, had these foreign works been able to be copyrighted here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Picasso’s famous painting Guernica, the British films of Alfred Hitchcock, stories by H.G. Wells, the drawings of Escher. I mean, these are building blocks of whole enterprises of artwork.

ADAM LIPTAK:

The government argues that American artists are better off because of analogous opportunities to get their work copyrighted abroad, where it couldn’t be copyrighted. The theory of the copyright clause of the Constitution, which grants copyrights for limited times, is that you want to give people an incentive to create by giving them a limited monopoly, but that ultimately their works will belong to everyone.

The Court though has already disappointed people committed to the public domain once, when about eight years ago it blessed a 20-year copyright add-on that didn’t seem to help incentivize creation because it was being given to people whose works have been created long ago.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Right.

ADAM LIPTAK:

So building on that case, there’s some reason to think the Court might accept this 1994 law, as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Here’s kind of a weird one: The Justice Department is asking the justices to decide whether a 2006 law making it a criminal offense to lie about being decorated for military service is constitutional.

ADAM LIPTAK:

The law is called the Stolen Valor Act. It’s a beautiful sort of law school hypothetical about the First Amendment. We hand out decorations to military personnel who give their all. Well, what if someone walks around with a medal he’s not supposed to have? Can you make that sort of lie a crime?

One of these cases arises in the context of some local politician saying he was awarded some very prestigious medal, and he runs for office on that basis. And, you know, the voters in some sense were misled and perhaps some people voted for him, you know, on the basis of this lie.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Right, but Adam, I know where you’re going with this.

[ADAM LAUGHS]

Politicians lie all the time! Supposedly, they pay a price in the ballot box for that. You don’t throw a person in jail for lying. I mean, once you start on that slippery slope, where would it end?

ADAM LIPTAK:

Brooke, I’m – I’m trying to present this case as neutrally –

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

- and as straight as I can, but sympathies obviously are with you. I mean, in general, the government should stay out of the business of regulating speech, particularly through criminal laws.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So, Scalia is gonna kill this one, right?

ADAM LIPTAK:

I think here he will be persuaded that you don’t need the full weight of the criminal law to go after the liar; you can rely on shame and other kinds of ways that society has dealt with lies since the beginning of time.

It’s a federal law, and striking down a federal law is no small thing. So I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the Court agrees to hear this case too.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Adam, thank you very much.

ADAM LIPTAK:

My pleasure, always good to be here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Adam Liptak covers the Supreme Court for The New York Times.