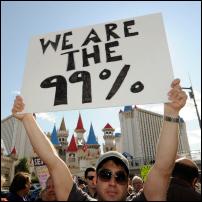

Occupy Wall Street

( Getty Images )

BOB GARFIELD:

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

And I'm Brooke Gladstone.

PROTESTERS:

The whole world is watching. The whole world is watching. The whole world is watching.

[CHANTING UP AND UNDER]

Increasingly, the world watches the protest called Occupy Wall Street, now finishing its third week camping out in lower Manhattan. Recent clashes in which police pepper sprayed and beat protesters with batons drew even the most resistant media outlets.

MALE PROTESTER:

Each new depiction of the abuses of the police on the First Amendment, the more ways of occupation will spread across this country!

FEMALE PROTESTER:

Yeah!

MALE PROTESTER:

And you should be proud of that, police, because you are participating in our media publicity campaign.

[CHEERING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Some Occupy Wall Street advocates complained about what they called a news blackout in its early weeks but, in fact, this progressive populist protest did better than its anti- government analog, the Tea Party. According to the Pew Research Center, the Wall Street protests made up 1.6 percent of the overall news hole in the week of September 26th to October 2nd.

The first Tea Party protests in February 2009 received no measurable coverage. True, much of the Occupy Wall Street coverage has been dismissive or worse, but the Tea Party condemned its coverage too. Soon, of course, the Tea Party scored pots of conservative money and a house organ in FOX News.

For now, Occupy Wall Street which calls for economic justice for the vulnerable but offers no specifics, no demands and no candidates, is on its own.

Thursday was sunny and fine, and Foley Square was full of people, many looking like they’d slept there, which they had. There was food, lots of cameras, the curious and the committed, the latter with signs condemning the one percent of Americans whose grip on wealth and power makes life so hard for the other 99 percent. The mood was good.

Bill Dobbs was sitting at a tiny table with a handwritten sign saying “Press” so people like me would have someone to talk to. He had worked with the AIDS activist group ACT UP years ago.

BILL DOBBS:

We're down here giving off a loud outcry in the shadow of Wall Street. It has now sparked other similar protests in other cities around the country. That's very important.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

How does it translate into action, something more than just a kind of esprit de corps without any focus?

BILL DOBBS:

It’s a very clear focus when you say Occupy Wall Street.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

You think?

BILL DOBBS:

Let me put it in this way: Easily 150, 200 or more outlets have sent staff down here to do stories, sometimes freelancers. When I look online at the leads, they've framed the issue, often revolving around economics.

And I think there's a problem in people hammering and demanding that there be a slogan or a list of things that people want because it's a huge project just to get attention. And that's happened.

Wall Street’s not gonna get reformed overnight, nor is Congress. But there's anger and despair that's brought people down here. There’s also camaraderie, community and fun. And those are the two ingredients that have enabled this protest to sustain itself against the NYPD and the weather for almost three weeks now. You wouldn't be down here if there wasn't some buzz around this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

There are a number of people who say the attention really riveted on this place when the cops pepper sprayed people, corralled people and so on. And then suddenly people were noticing what was going on in Wall Street in a way that they had not before.

BILL DOBBS:

Part of this protest is media production, dozens of people out with video cameras coordinating that, uploading it, live streaming. That's how the police misconduct came to light.

So we have one working group that’s dealing extensively with creating media to project what people are doing here. And some of us are working with media outlets to get the message through. There have been columns and there have been editorials, which have said, you might not agree with the way that people on this plaza are crying out, but the issues that are being raised could not be more important. It's, it's been a slow build.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

What's next? Do you have a plan?

BILL DOBBS:

Uh, right now the, the plan is to be here indefinitely and to do everything possible to bring more people into it.

People come in all the time. They want to know what’s going on. There was a sign one day on the plaza that said, if you make less than 250,000 dollars you should join us. Why? Because everybody's hanging by a thread.

And that's also true of members of the media. You know, I recall a broadcast producer coming through here. He’s very grumpy and he said, I’m really mad because I wanted to cover somethin’ else, and my boss assigned me to cover self-indulgent college students. I said, if I may, how’s your pension? He said, I don't have one. I said, you know, that’s part of the reason people are here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Some protests fizzle, some become movements, the result of an unpredictable alchemy of character, issue, tactics and timing. Michael Kazin teaches history at Georgetown University and is the author of American Dreamers: How the Left Changed the Nation. Does he see movement potential in Occupy Wall Street?

MICHAEL KAZIN:

For it to become a movement, it has to become organized, it has to have recognizable spokespeople. It has to have a strategy and not just a set of protest tactics. So this may or may not become one, but right now it is a protest campaign.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

It's often been likened to the Tea Party, which was often mischaracterized as being purely Astroturf, the, uh, child of a lot well heeled conservative activists. I mean, it was that, but it wasn't only that.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

No, I think the Tea Party was and is a quite sincere grassroots insurgency. It’s really the creature of 30, 40 years of conservative organizing on these issues. The rage of the Tea Party bubbled up partly because of the, uh, financial crisis, the idea that big banks were being bailed out by the government, and also a frustration with their own conservative president, George W. Bush.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

So what do you think Occupy Wall Street needs in order to become a movement?

MICHAEL KAZIN:

It needs to last longer [LAUGHS], of course, get alliances, not just with some labor unions but with perhaps, uh, immigrant groups, perhaps with some people in the left wing of the Democratic Party. It needs to do what the civil rights movement did, what the, uh, anti-war movement did in the 1960s, what the labor movement did in the 1930s, which is to appear to be the voice of people who have not really had a voice about their discontent, their anger with what’s happened to, uh, the American economy.

What we're seeing I think, uh, between Tea Party people and the Wall Street protesters is a battle to define who's to blame for our economic calamity, who's to blame for the lack of jobs, who's to blame for the political system not really responding.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

I think that the Occupy Wall Street protest has undergone a transition of some kind in the last week, that somehow it's crossed over into being taken seriously.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

Oh, I think you’re right. I think you’re right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Why is that? It's almost conventional wisdom: they can't go anywhere without goals, they can’t go anywhere without organization, they can't go anywhere without clear demands and party affiliations. They actively resist these things. They want to move ahead in a inchoate fashion, as a – an expression of discontent.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

Well, I think at this stage being a little inchoate, being a little incoherent, even, but being very clear what you’re against more than what you’re for enables lots of people to part, with their own reasons. But after a while, when we're getting into November and December in, in the Northeast, clearly people aren’t going to continue to camp out in large numbers.

So at this stage what they're doing is very effective. If it continues to go on, people in the media will say well, you did this for two months. What are you gonna do next?

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

But I'm still puzzled. Why are they even effective now?

MICHAEL KAZIN:

Well partly, talk about the media, I think there has been a sense that this economic discontent, and not just here but elsewhere in the world that said why aren’t Americans angry about this, why are the only Americans angry, angry about the government?

So I think, for very good reasons, a lot of people in the media have been looking for this to happen for some time, and once it starts to happen, they cover it and the coverage itself helps to generate more interest.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

The Vancouver-based anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters kicked this whole thing off with a call to occupy Wall Street last summer. Its co-founder told Salon that Adbusters was a student of the Situationist movement. This is the idea that if you have a very powerful meme, an idea, and the moment is right, then that is in itself enough to ignite a revolution.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

Well, the Situationists did not ignite a revolution. They did ignite a very powerful movement that was pretty short lived in France and a few other countries. And they were influential to a certain degree among some New Left intellectuals in this country, as well.

The fact that most people in your listening audience have never heard of them itself [LAUGHS] I think is a –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- is indication that their influence was interesting but not highly significant, I don’t think.

One thing they did make clear, and this was certainly happening in the sixties with people like Abby Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, the Yippies, is that they realized that if you can be humorous and, uh, provocative and make the powers that be look small, look ridiculous, you can really get people on your side.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

I guess I subscribe, to my own surprise, to a kind of ether theory of movements, in that, you know, in the Tea Party you had all of this anger going into the ether, and it didn’t really matter whether the facts were right or wrong; there was a kind of change in the temperature. And suddenly these ideas were everywhere, just filling the air.

It strikes me that this is an attempt to change the temperature again, to change how people see the world.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

As, as a historian, I think that nothing comes from nothing. And it’s still in numbers fairly small. That has to be said.

But then, of course, the four people who sat in at lunch counters in, uh, Greensboro, North Carolina in 1960 was also a small group. But they were representing a larger group. So size itself isn’t enough.

But I think people in the media are groping to sort of understand who these people are, whether they are really on the left or whether they are just a group of fairly non-ideological people. All these questions seem to be open.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Do you have any notion of which way you think this could go?

MICHAEL KAZIN:

This is fun about being a historian. You know, these – these things are not predictable. They really have to keep adapting to changes in the structures that they are protesting. People make their own history but not as they please, as this, uh, famous leftist Karl Marx wrote [LAUGHS] in the nineteenth century.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Michael, thank you very much.

MICHAEL KAZIN:

Oh, you’re very welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Michael Kazin’s new book is American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation.