BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone, with a cautionary tale about the business of games.

[TETRIS MUSIC UP AND UNDER] This is the sound of compulsion, the drive to stack and pack various colored blocks as they rain down a digital screen. This is Tetris. Though it had been popular in arcades, even home screens, for years, it became an icon only when it came bundled with Nintendo’s Game Boy in 1989. That’s when Nintendo was riding high after having singlehandedly revived the video game industry back in 1985. That was two years after video game giant Atari was caught secretly burying 14 truckloads of unsold games and consoles in a desert landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Atari was trying to cover up dismal sales that were sinking the stock price of its parent company Warner Communications. The video game business was dead. You see, anybody could make games for Atari’s console, and every conceivable business did. But games are different from TV shows or movies or commercials, something those outsiders didn't understand. And so, as On the Media producer P.J. Vogt explains, they killed the golden goose by stuffing it with ill-conceived, atrocious fare.

P.J. VOGT: How atrocious? Well, [GAME BEEPS] there was Chase the Chuck Wagon by Purina, the dog food company, or Picnic by Quaker Oats [BEEPS], where you had to protect your lunch from bugs.

By 1985, the flood of bad games had shrunk the game industry’s value, from three billion dollars down to just a few hundred million dollars. And that’s when our story really starts. That winter, Nintendo sent out salespeople to try to pitch U.S. retailers on a new console that was doing really well in Japan. Video game historian Steven Kent is the author of First Quarter.

STEVEN KENT: Retailers weren't exactly excited to see them. One Nintendo salesman told me that he was afraid when he went to Sears Roebuck that they were gonna march him out the door and beat him up in the parking lot.

P.J. VOGT: Storeowners had already been burned by unsold video games. Nintendo knew that it had better games and a better business model, but it had to trick retailers into stocking their system. So it came up with a Trojan horse. Nintendo bundled the video game system with an accessory, a robot toy named R.O.B.

[CLIP]:

MAN: Play with R.O.B., the extraordinary video robot. Batteries not included.

[CLIP SOUNDS UP AND UNDER]

P.J. VOGT: The way they pitched it to retailers, R.O.B. was a toy that just happened to come with a video game.

STEVEN KENT: When they went to retailers, when the retailers said, we don't want video games, they'd say, no, this isn't a video game, this is a robot game. And the retailers would say, oh, okay, robot games. As long as it’s not video, we're happy. That was how they got in the door.

DAVID SHEFF: Once they started to get the video game system in the hands of kids, the cycle began.

P.J. VOGT: David Sheff is the author of Game Over.

DAVID SHEFF: They went from having zero shares in an industry that was worthless to having 90 percent market share of an industry that grew to become a one-billion-dollar, then a two-billion-dollar, then a three-billion-dollars, and then eventually a five- and six-billion-dollar industry.

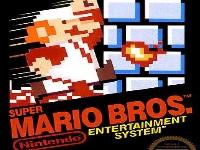

P.J. VOGT: Nintendo’s game designers, led by Shigeru Miyamoto, fully grasped that they were creating a new medium. Their games were artful, imaginative and addictive.

[GAME SOUNDS/UP AND UNDER]

DAVID SHEFF: Mario was this plumber that was kind of pudgy and, you know, wore overalls, the last person you expect to be a hero in a video game. His brother, Luigi [LAUGHS], you know, another unlikely hero. They were just kind of two, you know, funny and dorky guys who went off on these great adventures. And it was so exciting to find flying turtles, mushrooms that you'd jump on that, you know, you could fly.

P.J. VOGT: Each game evoked its own vivid world. You could play The Legend of Zelda as Link, an elfin warrior with a sword and a boomerang on a mission to save a princess, or you could play Metroid as Samus, an intergalactic bounty hunter who removed his helmet in the game’s last act, revealing that he was actually a she.

DAVID SHEFF: [LAUGHS] Maybe it sounds silly but, you know, at the time it was exciting because, you know, we really had identified with this character, and there was this great surprise waiting.

P.J. VOGT: Nintendo’s games created demand for their console, and once people got their hands on the console they wanted more games, more than Nintendo could create alone. Nintendo needed outside developers to help create games for them, but they were scared of repeating Atari’s mistake of letting the Purinas of the world ruin their market with bad games. Howard Lincoln, former chairman of Nintendo of America.

HOWARD LINCOLN: It was the failure of Atari to have any kind of quality control, not only over its own games, but also games by third party companies. We had to come up with some kind of a solution.

P.J. VOGT: The solution was a proprietary chip that Nintendo put in every game cartridge. Their system was designed to only play games with the chip inside them. To qualify for the chip, games had to first be awarded Nintendo’s Seal of Quality. Steven Kent.

STEVEN KENT: The Nintendo Seal of Quality meant a lot of things. Basically what it [LAUGHS] meant was that you gave Nintendo 10 bucks a cartridge for every cartridge that came out.

P.J. VOGT: This was new. Before Nintendo, game hardware companies didn't typically profit from games that third party developers designed for their hardware. The seal made Nintendo a lot of money, but it also made universal quality control possible. For Nintendo, that meant good clean games, no violence or sex, no politics or religion. Once, an outside developer submitted a game featuring female villains. Steven Kent.

STEVEN KENT: Howard Lincoln called the head of this company in and said, I've got a problem with this game, there’s violence against women in it. And the guy said, no, there’s no violence against women in this game. And they started playing it for a few minutes, and out come these female gangsters who you punch them out and they fall down and disappear. And the president of the other company looked at him and said, oh, you mean the transvestites.

P.J. VOGT: Game makers tolerated Nintendo’s censorship because there was no alternative. From the mid-'80s into the '90s, Nintendo completely dominated the U.S. home video game market. Their first successful competitor was another Japanese company called Sega. Sega hired an American, Tom Kalinske, to figure out how to beat Nintendo. Kalinske remembers traveling to Japan to convince Sega’s board of his strategy. Through a translator he told them that Sega would have to sell cheaper games, give third party developers more freedom and, most crucially, cater to a more grownup market.

TOM KALINSKE: I said, okay, guys, and we're gonna go after teenagers and college age kids; we'll leave Nintendo with the younger kids, and we're gonna take on Nintendo in a very direct manner in our advertising. Of course, you know, everybody on the board started talking in Japanese, and I didn't understand a word of it. And it went on for like an hour. And a guy was whispering in my ear every now and then, sort of trying to give me the gist of what different people were saying. And it was all bad.

P.J. VOGT: In the end, the board actually took Kalinske’s advice. Sega offered older gamers what Nintendo lacked, racier content, violence and good sports games. In-your-face TV ads highlighted the strength of Sega’s Genesis console.

[SEGA TV AD/SOUND UP AND UNDER] A big coup for Sega was its adaptation of a ludicrously violent arcade game called Mortal Kombat. It was a martial arts game, where players would fight each other to submission.

[MORTAL KOMBAT SOUNDS] And then, as Steven Kent remembers:

STEVEN KENT: Once you subdued your opponent you'd do these finishing moves where you'd pull a guy’s skull and spine out of his body or other really bloody things. And Nintendo said, you know what, we don't want that on our game.

P.J. VOGT: The home version of the game came out simultaneously, both on Sega’s Genesis and on Nintendo’s new console, the Super NES, but with a crucial difference. Howard Lincoln.

HOWARD LINCOLN: We ultimately decided that, you know, the blood had to be green, but on the Sega version of Mortal Kombat it was red.

P.J. VOGT: Sega gobbled up market share. When Kalinske started in 1990, Sega held less than 8 percent of the market. By 1992, that number had grown to 55 percent. Meanwhile, Nintendo stuck to their original vision for games, the one that had revived a dead market in 1985, games that were G rated, tightly controlled and beautifully made. That stubbornness cost Nintendo –

[GAME SOUNDS/UP AND UNDER] - as first Sega, then Sony, then Microsoft each took progressively more of Nintendo’s market share. Today, Nintendo has rebounded on the strength of its Wii console but the video game world has changed. No single giant dominates, and the big hardware companies just don't have the clout to dictate what content they'll allow on their consoles.

[CALL OF DUTY GAME SOUNDS/UP AND UNDER] This holiday season, the most popular video game in stores is one that never would have been approved by Nintendo execs back in the '80s or '90s. For starters, it came out on nearly every platform at once – Microsoft Xboxes, Nintendo Wiis, Sony PlayStations and personal computers. It’s called Call of Duty: Black Ops, and it’s a violent shoot-'em-up game, with political overtones. It’s the latest installment in a franchise that’s made its creators more than three billion dollars so far. And it came from a developer named Activision, a company started by rogue programmers who'd abandoned a failing hardware company in the early '80s, a company called Atari.

[GAME SOUNDS/UP AND UNDER]