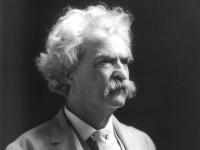

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The tell-all book of the year recently debuted as number two on The New York Times Bestseller List and is now available for your delectation. Among the words used to describe it are: uncensored, shocking, a realer, darker Twain. That’s right, Twain, as in Mark. Apparently, never this Twain have we met, until the publication of The Autobiography of Mark Twain: Volume 1. It’s making news because the author slapped a century-long embargo on it, and finally that time is up. But is it really such a sizzler or merely deft brand management from beyond the grave? Writer and Yale Ph.D. candidate Craig Fehrman recently quoted in Slate a letter that Twain wrote to his friend Walter* Dean Howells in 1906. It goes: “Tomorrow I mean to dictate a chapter which will get my heirs and assigns burned alive if they venture to print it this side of A.D. 2006 – which I judge they won't. There'll be lots of such chapters if I live three or four years longer. The edition of A.D. 2006 will make a stir when it comes out.” Well, he did live four years longer, but really, Craig, what conceit – what accuracy.

CRAIG FEHRMAN: You've got the prestigious literary magazine, Granta, hyping what they were calling the first exclusive excerpt from Twain’s autobiography. You've also got the online blog, Gawker, talking about Twain’s vibrating sex toy [BROOKE LAUGHS] so you've got [LAUGHS] the entire pop cultural spectrum really interested in this book.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think it’s at all remarkable that Twain seemed to foresee what kind of excitement his embargoed work would generate a century after his death?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Absolutely. Twain was brilliant at managing his brand. That’s exactly what this idea gets at. Most writers don't want to sully their hands with that side of the business. Twain really innovated in that side of the business. When he first conceived of the idea of the autobiography in his 30s, he thought that it would allow him to be more candid about both himself and about his various contemporaries. But he slowly started walking back this idea. He would write “50 years” by some passages, as in don't print these for 50 years, “75” by others. So by keeping all these different dates in play and being playful with it, Twain gave both his editors and future literary executors permission to kind of play with this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There was a financial element to all of this, wasn't there?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Oh, absolutely. Money was never far from Twain’s mind when it came to the autobiography. I mentioned that he published a few things in his own lifetime. He took the proceeds from that and ended up building a new house, and for a while they called it the “Autobiography House.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So how much of an embargo is this really? I mean, there were three previous editions of Twain’s autobiography, one in 1924, one in 1940, one in 1959. How much is new in the 2010 version?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Well, in the first volume, only about five percent of the material is actually new. The next two volumes, which are about five years away, will have as much as 50 percent new material.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And what’s in that five percent?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Well, there’s all kinds of stuff. The Granta excerpt has Twain talking about a farm and reminiscing about his childhood days. He talks about Theodore Roosevelt and the way American soldiers are working abroad and the damage that they're doing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Was he talking in this section about the Spanish-American War at the turn of the 20th century?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Right, and the idea that the American soldiers were, quote: “uniformed assassins.” That’s the phrase he used. But, again, that’s a phrase that crops up in Twain biographies. It’s not something that’s being heard here for the first time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s a section that apparently his daughter, who was his executor for a long time, didn't want out. He’s writing on Christianity and he writes: “Ours is a terrible religion. The fleets of the world could swim in spacious comfort in the innocent blood it has spilled.”

CRAIG FEHRMAN: He was very willing to criticize organized religion.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But he only used such strong terms in the embargoed work.

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Twain definitely saved his frankest and most damning passages for the embargo. His famous line in the preface was: “In this autobiography I shall keep in mind that I am speaking from the grave. From thence I can speak freely.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Managing your brand posthumously.

CRAIG FEHRMAN: I think one thing worth noting is that to manage your brand you have to have a brand in the first place, and that’s something that Twain was uniquely qualified to have. He was the kind of celebrity that would get noticed as he was walking the streets of New York. That celebrity, in addition to his writing, allowed him to package his life in a way that was unprecedented. Twain realized that good marketing doesn't just make money. Good marketing also ensures that you’re being talked about. We've mentioned these three previous editions. They were not only bestsellers but they also made front-page news. And so these ensured not only that the Twain bottom line increased but also that the Twain reputation increased.

HAL HOLBROOK AS MARK TWAIN: Oh, I was sorry to have my name mentioned as one of the great authors -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Actor Hal Holbrook doing Twain.

HAL HOLBROOK AS MARK TWAIN: - because they have such a sad habit of dying off. Chaucer is dead. So is Milton and so is Shakespeare.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Tell me about how he wrote this work. I mean, a lot of this work wasn't actually written at all. It was dictated.

CRAIG FEHRMAN: That's right. Twain experimented with this beginning in his 30s, trying to come up with different ways to do that. The method he finally settled on was through dictation. When Albert Paine came on to do Twain’s biography he needed raw material and so Twain said, well, let's do dictations, but let me use the dictations themselves for my autobiography.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And this was something of a postmodern work. It wasn't chronological when he wrote it. It was more or less stream of consciousness?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Right, the writing of the autobiography can feel as modern as the marketing of the autobiography. There are nice little set pieces where he'll tell a story or an anecdote or expand on something at length, but then he'll jump forward decades or jump backward decades. This was the voice and the tone he wanted, and hoped – although, again, you can never tell how serious he’s being about this stuff – he hoped that this was a model that future autobiographers might consider.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think that his current living, breathing publicists are overselling this a bit by calling it “shocking?”

CRAIG FEHRMAN: I do. The image that everyone’s trying to put out there is a realer, darker Twain, a Twain that we need now more than ever. I'm certainly not going to be disappointed that Twain’s on the front page of The New York Times. It’s a wonderful book, and I'm excited that it’s going to be on shelves, but it’s not exactly the mass market literary event that it’s being portrayed to be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Fundamentally, did it change your view of this very public man?

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Honestly, no, because the raw materials have been processed by various biographers. Twain has had the benefit of more biographies than just about any other American literary figure. It was fun to read, it was nice to have, but the ideas themselves were already in the public conversation. And that’s what makes this idea that we're getting the real Mark Twain finally so mystifying.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Well, Craig, thank you very much.

CRAIG FEHRMAN: Thanks for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig Fehrman is a Yale Ph.D. candidate and freelance writer who recently wrote about Twain’s autobiography in Slate.

McAVOY LANE AS MARK TWAIN: Humor is nothing more than the good-natured side of the truth.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Actor McAvoy Lane doing Twain.

McAVOY LANE AS MARK TWAIN: And laughter without philosophy woven into it is but a sneeze at humor. Genuine humor is replete with wisdom, and if a piece of humor is to last, it must do two things. It must teach and it must preach – not professedly. If it does those two things professedly, all is lost. But if it does them effectively, that piece of humor will last forever – which is 30 years.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER] * CORRECTION: William Dean Howells