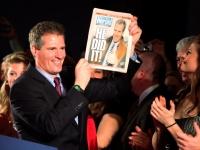

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield. When the death of Senator Edward Kennedy opened a Massachusetts Senate seat and Martha Coakley was anointed as the Democratic nominee, it seemed like a done deal. The GOP would nominate a token candidate, but a Scott Brown drubbing was a foregone conclusion, preserving a safe Senate seat and the Democrats’ 60-vote majority. Oops!

[CLIPS]:

[SOUND OF CROWD IN BACKGROUND]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Oh, this is clearly a huge upset, a shock for Democrats.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Coming fresh off a stunning victory in the Bay State, Scott Brown made the rounds on Capitol Hill today, meeting…

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: A Republican Senator from Massachusetts, in Ted Kennedy’s old seat? Well, you've got to think that Republicans are pinching themselves this morning. Democrats…

[END CLIPS]

BOB GARFIELD: It was fairly close to Election Day before anybody in the national press noticed that voters might influence the narrative by stubbornly – voting. But surely the local political press had its finger on the pulse of the electorate. Surely Boston reporters and editorialists saw beyond the conventional wisdom. Not really. They blew it, too. David Bernstein is a political reporter for The Boston Phoenix, and he joins us now. David, welcome to the show.

DAVID BERNSTEIN: Thanks for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: I don't wish to embarrass you, but I must read from your piece dated January 8th, 2010. “In less than two weeks, when Massachusetts voters elect Martha Coakley to the U.S. Senate, let's not pretend that Republican State Senator Scott Brown has any chance of pulling off a monumental upset. They will trigger a massive domino effect that has the state’s political class buzzing with anticipation.”

[LAUGHTER] What have you to say?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: [LAUGHS] I've had that line come back to me quite a bit. To be honest with you, I didn't see and nobody else around here saw the possibility – kind of huge, an over 50-percent turnout that was required to bring a Republican into office. There was such an enormous advantage that Martha Coakley had with the Democratic base that in a special election in the middle of January it was assumed that that would be plenty for her to be able to win.

BOB GARFIELD: It was assumed. Mistakes were made. And in fairness to you -

[LAUGHTER] - you were by no means alone in this. I'm going to read from an Op-Ed in The Boston Herald. Quote, “Is there any chance Scott Brown can win? Technically, yes, in the same sense that it’s possible Tiger and Ellen Woods could make out on the set of Larry King.” And…

[LAUGHTER] - in The Boston Globe, “Can Scott Brown win? Short of a political miracle, no.” So what dots did you fail to connect over the past several months?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: I think that we perhaps failed to see the wide swath of independent voters here in the state who are disgruntled about the economy, about the state government, about the way that the federal government is not seeming responsive to their needs, the extent to which they would get involved and enthused about participating in this election.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, that’s one dot. Is there anything else? Did you pay attention to what the Democratic Party was doing and not doing in its campaign?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: We were and, in fact, I had written quite critically, and I wasn't the only one, about how Martha Coakley ran her campaign, pointing out that the campaign was not doing a very good job of raising money, that they were not on the air with ads early, that she was not barnstorming the state. We were aware of all that sort of thing but we were not taking seriously the notion that, that could have [LAUGHS] anything to do with erasing what seemed like a 30-point gap in the polls. So it wasn't necessarily that we didn't see the dots. We just didn't realize that they were [LAUGHS] going to add up to so much.

BOB GARFIELD: You mentioned the polls. There was no exit polling, so it’s hard to know exactly what motivated individual voters on Election Day. But there were tracking polls during the course of the race. Were there not enough of them?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: There was a poll done by The Boston Globe that came out about a week and a half before the election, and that’s a very influential thing in terms of the perception of the race, that showed a 15-point lead for Martha Coakley. So it wasn't that we weren't seeing some movement in the polls and everybody started to pick up on it, but there wasn't solid evidence that the gap had really closed completely until very late, the very last week. And even then, frankly, maybe we didn't take those polls seriously enough because we felt like well, we know the Massachusetts electorate. And so, maybe we were a little blind to the polls because we thought we knew better.

BOB GARFIELD: Now that the election results are what they are and the national press is trying to figure out where it went wrong, are you seeing any big holes in their post-election coverage?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: Yeah, I think that the national media tends to interpret local events based on the things that they know about, which are national issues, so they're tying things in very much to the National Health Care Reform Bill, when I think that this election had a lot more to do with frustrations that people have to state Democrats who are running the state. This is an unusual state, where the Democrats really completely control the state government, so frustration with anything to do with state government translates into frustration with the Democrats. And I think that that played out a lot in what was energizing people to vote against the Democrat in this election. I think that the national media that is sort of swooping down, trying to interpret this and say how it’s going to affect other races, and so forth, are missing that because they're looking at a national picture.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, David, I've got to tell you, you are absolutely my hero for coming onto this program to be slapped around.

[LAUGHTER] Tell me though, what will you do differently from this point forward?

DAVID BERNSTEIN: Well, I think that we have to try to do a little more analysis and less prognostication, perhaps, and also take more seriously trends that are not happening within the circles that we tend to talk to. You know, we tend to talk to folks who are very close to campaigns or very, you know, in elite circles and so forth, and oftentimes those folks are out of touch with what the rank-and-file folks are hearing and seeing out amongst the people. So we need to find ways to be more in touch with that and get out of the circles that we tend to trap ourselves in.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, David. Thank you very much.

DAVID BERNSTEIN: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: David Bernstein covers national and Massachusetts politics for The Boston Phoenix.