BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I'm Bob Garfield. In the late 1980s, Congress passed the Film Preservation Act, which authorized the Library of Congress to select and preserve 25 American films each year that are, quote, “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” Now there are 500 movies in the Library of Congress collection, some of which you'd recognize.

[CLIP]:

MARLON BRANDO AS DON CORLEONE: I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.

[END CLIP]

[CLIP]:

HUMPHREY BOGART AS RICK BLAINE: Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world -

[END CLIP]

[CLIP]:

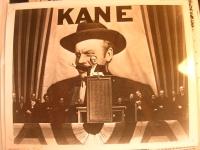

ORSON WELLES AS CHARLES FOSTER KANE: [WHISPERS] Rosebud.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: But many of the chosen films are virtually unknown. Film critic Daniel Eagan has written a book about all 500 movies, all but 3 of which he's watched in full. It’s called America’s Film Legacy: A Guide to the National Film Registry. Eagan says they aren't the best films ever made, but they are the most important.

DANIEL EAGAN: Because of what it captured at the time, like the Republic Steel Strikes Newsreel Footage, or because it influenced subsequent filmmakers, like Night of the Living Dead did, or because it was an experimental process that eventually developed into something else, like Cinerama or 3-D.

BOB GARFIELD: There is this whole category of films that you would otherwise, you know, maybe not even know about which are deemed historically significant, and a lot of them are what are called “orphan” films. What are orphans?

DANIEL EAGAN: Orphans are films that don't have any parents, at this point. Either the filmmakers have died or the company that produced the film no longer exists, or it’s a genre or a film that is considered not important enough to preserve. Among these are newsreels, cartoons, musical shorts, documentaries, all kinds of films.

BOB GARFIELD: Can you give me some examples of important orphan films that you've written about in America’s Film Legacy?

DANIEL EAGAN: Yeah, sure. There’s Master Hands, which was made in the mid-'30s by the Jam Handy Organization. It’s a half-hour film about making cars that was probably made for the General Motors shareholders at one of their shareholder meetings.

[CLIP]:

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

NARRATOR: From the master hands of the toolmakers to the hands that master the great machines.

[END CLIP]

DANIEL EAGAN: It’s like a feature film. It’s really beautiful. It has a symphonic score. It’s done in 35 millimeter. Master Hands is one of the shining examples of industrial films.

BOB GARFIELD: Among the other treasures that you write about is a kind of a proto-music video, a 17-minute Bessie Smith short from 1929, St. Louis Blues?

DANIEL EAGAN: St. Louis Blues. That’s the only film of Bessie Smith that exists.

[CLIP]:

BESSIE SMITH SINGING: I hate to see that evening sun go down.

CHORUS: Yes, sister.

BESSIE SMITH SINGING: Yes, I hate to see that evening sun go down.

[END CLIP]

DANIEL EAGAN: Well, it was made after her recording, so they made an actual narrative up about it, much as they do in music videos today. They did promote it as a Bessie Smith film, and they did promote the St. Louis Blues tie-in. And, as a matter of fact, as a short it actually got larger advertising than the features that it was supporting in theaters. And it was considered a significant film at the time.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, on that very subject of multi-platform promotion, you know, the simultaneous release of print and film and recording elements all meant to work in symbiosis, we think of that as a modern phenomenon. You found some proto-synergies. Tell me about them.

DANIEL EAGAN: Well, I guess I was amazed to find out that people were using the techniques that people use today back 100 years ago, and doing it very well. There was a play called The Widow Jones, which was not a big hit but it was enough of a hit to spark a series of articles in the newspapers about whether kissing on stage was a social problem, an increasing social problem. And then they filmed the end of The Widow Jones, the actual kissing sequence. So you could go see the play The Widow Jones, go across to street to see the movie of the kiss, and then read about it in the papers and magazines at the same time. It was really a remarkable way to cross-promote all three media.

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHS] AOL-Time Warner, eat your heart out.

DANIEL EAGAN: Exactly. [LAUGHS]

BOB GARFIELD: One film you saw that clearly has tremendous historical significance was called Siege, shot during the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. Can you tell me the history of that film?

DANIEL EAGAN: Sure. Julien Bryan, the man who made Siege, he was in Warsaw right when Germany invaded Poland. He was the last neutral filmmaker there. And he smuggled the footage out, brought it back to New York and showed it in an RKO newsreel called Siege.

[CLIP]:

NARRATOR: German planes dive low over the city as they attack.

[SOUND OF GUNFIRE] Polish anti-aircraft batteries actually made many direct hits. About 50 German planes, all told, were brought down while I was in Warsaw.

[NEWSREEL SOUNDTRACK/UP AND UNDER]

[END CLIP]

DANIEL EAGAN: This was the first time people in the United States could see the actual effects of war, the actual effect of total war, with the Germans attacking apartment buildings with incendiary bombs, attacking hospitals, attacking churches. And I think it actually helped change the climate and made it easier for the United States to enter into World War II.

BOB GARFIELD: And yet kind of vanished.

DANIEL EAGAN: Yeah, what happened is that it got appropriated by other people. Frank Capra made of series of films for the government called Why We Fight, which was supposed to be able to convince the audience that we were supposed to enter the war, and he started incorporating Julien Bryan’s footage into his documentaries. And then, you know, once the war started, nobody really wanted to see how Warsaw had been destroyed. Julien Bryan continued to make a number of movies around the world, and he always held onto this material. His son Sam donated it to the Steven Spielberg Archive at the National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. However, he’s got 800 more cartons of material in a warehouse in New Jersey and doesn't have the funding to take care of these other films that his father made.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, Daniel, so you've seen the most notable films in American history. What have you learned?

DANIEL EAGAN: I've learned that you can't really tell what’s important to save in film. You can't tell when it’s going to be important and how it’s going to be important. There are films that were made during World War II, home movies made in Japanese internment camps. Nobody knew at the time that they were going to be a valuable insight into how society was working then. And aren't we glad that someone actually saved those films and other films like it.

BOB GARFIELD: Daniel, thank you very much.

DANIEL EAGAN: It was great talking to you. Thanks for this opportunity.

BOB GARFIELD: Daniel Eagan is a film critic for Film Journal and The Hollywood Reporter. His book, America’s Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, came out this month.