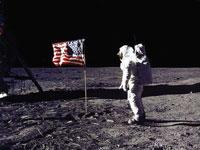

Forty years ago this month, the United States put a man – actually, two men – on the moon.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

BOB GARFIELD: The global media moment, seen by about half a billion people worldwide, was the culmination of more than a decade of NASA trial and error - building rockets, weathering setbacks and trying to outpace the Russians, and also forging an uneasy relationship with the press. Harlen Makemson is the author of a new book, Media, NASA and America’s Quest for the Moon. He says that the early years of the space program were reported on by a largely uncritical press enthralled by the image of clean-cut, God-fearing astronauts who were going to put their lives on the line to win the Cold War space race for the United States.

HARLEN MAKEMSON: And the mass media was very much in tune with perpetuating that image. They were depicted not only in training but at home with their wives, in John Glenn’s case especially, teaching Sunday school, those sorts of things.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, so everything is swell when the launches are successful, when Alan Shepard goes into space for the first time and John Glenn is the first human being to orbit the Earth. But there are accidents, as well. Gus Grissom is trapped in his capsule after splashing down in the ocean. Later, in the early Apollo program, Grissom and two other astronauts die in a launch pad fire. How did the press behave when things didn't go well?

HARLEN MAKEMSON: I'll tackle the Grissom flight first. Beforehand, NASA had allowed the networks into the Mission Control to sort of shoot dummy footage of people at the controls and on a headset talking to the astronauts, and NASA said, use however you want to. So as radio calls were coming in from Grissom splashing down, here’s TV inserting pictures of people in Mission Control when – NASA didn't really shoot straight on what happened – when the hatch came open, water came in. Of course, the big break was during Apollo 1. This is where you start to see the press being critical, not only asking questions of how this could have happened, but the way NASA handled the aftermath was just one bungling after another. The initial press release, the wording - there’s been a fire, quote, “involving fatality.” Some that covered NASA regularly swear there was an “a” involving “a fatality” initially. The head PR guy at Houston said, well, they died instantaneously, there was no suffering. Days later, The New York Times gets a hold of a tape from inside the capsule, where there had been screaming, and one of the astronauts said, “Get us out of here,” just one thing after another where NASA just performed horribly in being upfront, in giving information and being contradictory, never really tying up those loose ends. And NASA took a real beating throughout that. BOB GARFIELD: And didn't learn anything. I mean, it’s got this love/hate relationship with the media, using the media to advance its program and then clamping down when there’s something unpleasant to report. Did NASA ever come to terms with this dual relationship?

HARLEN MAKEMSON: Yes, but not consistently. One of the interesting things about Apollo 1 is Julian Scheer, a former reporter, had taken over the NASA PR reins in about ’64 and espoused what they called the Open Program, that, you know, we're going to show you what goes on. If there’s a problem, we're going to let you know about it. And that all kind of fell apart for Apollo 1, for whatever reason. But after that, when you got to Apollo 13, when there were the problems with the oxygen tank on board, NASA by that time has put a pool reporter inside Mission Control who’s able to get information more quickly to the other reporters. In pockets, yes, they did learn from it. But then when we get to the first space shuttle explosion, they essentially made all the mistakes again.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, so Apollo 1, there’s a fatal accident killing three astronauts on the pad. But the next nine Apollo missions go swimmingly, and then there’s Apollo 11, the most important space shot ever. We put a man on the moon, and it was a media event worldwide.

HARLEN MAKEMSON: Yeah, and basically everywhere except China, which essentially didn't tell people anything about the mission, essentially anywhere else where there was a television available, people were tuned into this. But, you know, when we think about how fractious the late '60s were and how one event, however briefly, brought not only the country but the world together for a few hours, it was quite remarkable.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, actually, more than a few hours. This was one of the great examples, first examples of wall-to-wall coverage.

HARLEN MAKEMSON: Yeah, 30 hours, if you were counting at home. Of course, Cronkite at CBS dominated, and he was completely immersed into this stuff. CBS had remotes in New York. They had another one out in Downey in California, with models of the spacecraft, etc. NBC converted its giant studio into a space center. They had a full-scale model of the actual lunar module. Again, other than liftoff, a couple of broadcasts from inside the space capsule and the actual walk on the moon, most of it was not open to TV cameras, so TV sort of had to recreate a lot of this stuff, if you will.

BOB GARFIELD: Did the media actually ask the fundamental question of why were we there, because of man’s imperative to expand his frontiers? Were we there for missile development and for Cold War reasons? Were we there for pure science? Did anyone wonder why?

HARLEN MAKEMSON: By large part, the networks were praised for their coverage of Apollo 11. In some circles, though, that was some of the criticism, that there was no real serious discussion of, okay, we're going to get to the moon, now what? Or was it worth it? A couple of the networks had a couple of discussions, one between Kurt Vonnegut and Arthur C. Clarke, the science fiction writer, about the pros and cons of the space mission. Thirty-plus hours of coverage, there was plenty of time [LAUGHS] to do those sorts of things.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to ask you one more thing. Now, we're talking because of the 40th anniversary of the moon landing, but as you look at the coverage of NASA since, I mean, two horrific catastrophes and the end of the space shuttle program just around the corner, President Bush’s declaration that man will [LAUGHS] explore Mars, it strikes me that through all of that, the public and media interest in the space program has substantially waned.

HARLEN MAKEMSON: In looking at this, one of the interesting things was the support for the space program was more sort of peaks and valleys, really, in the 1960s. It was not necessarily sustained. There was a Harris Poll that came out just a couple of weeks from the moon landing that 51 percent to 41 percent of the public thought that going to the moon was a good idea. It reversed the results of a similar poll a few months earlier. So it seemed like there was a major shift around Apollo 11, but a second question, I think, really opened up what was going on, that asked was the four billion dollars a year for the space program worth it. And a majority said no, and that number basically hadn't moved since the mid-1960s. So I think there were spikes of interest, the John Glenn flight, the first space walk by Ed White, Apollo 11. Apollo 13 got a lot of interest. But, by and large, I think the public was really ambivalent all along about space, and they wanted to see spectaculars. Of course, now that we've been on the moon, spectaculars are gone. So, what is it that’s going to get the public interested in exploring space more? And that was part of what NASA was hoping to do by televising the activities in space. They thought that it would make them willing to go out and spend more money for Mars exploration, etc., which never really turned out to be the case.

BOB GARFIELD: Harlen, thank you very much.

HARLEN MAKEMSON: Thanks. It was great talking with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Harlen Makemson is an associate professor of communications and media history at Elon University in North Carolina.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER] Coming up, Russian premier causes riot in supermarket, and other absurdities from the Cold War. This is On the Media from NPR.