Missed Connections

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. The White House wants all Americans to have access to high-speed Internet service and has committed some seven billion dollars in stimulus money to that end. Much of that money will go to rural America, where broadband penetration has climbed to 46 percent, according to a Pew Internet and American Life Project Study released this week. The stimulus package also holds 350 million dollars for broadband mapping, to learn who has service and where. After all, how do you fix a problem if you don't know where it is? That’s a crucial job, and it’s likely to go to the nation’s largest broadband coverage mapping company, Connected Nation. Some consumer groups have a big problem with that. Mark McElroy is Connected Nation’s Senior Vice President of Communications. Welcome to the show.

MARK McELROY: Thank you, Brooke. It’s good to be here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So your track record thus is based on the maps you've done or are in the process of doing for about ten states, right?

MARK McELROY: That's right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, in order to make your maps, you canvas all of the delivery opportunities in the area, but you don't actually find out who has coverage at what price and at what speed. In other words, you [LAUGHS] don't do a kind of coverage census, and many critics say that this is actually the most critical information.

MARK McELROY: We verify our maps through multiple systems. One, we invite consumers to view our maps. They're publicly available. They can plug in their actual address and it will identify for them who is a provider of broadband services to their home or business. Where there are inaccuracies, we encourage them to get in touch with us. And our maps, they're best envisioned as a living document, if you will, because deployment conditions change on a nearly daily basis. We update the map in nearly a real-time fashion. We also do consumer research that’s relevant down to the county level. In some states, you know, we'll do a sample size of 10 to 12,000.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: More like a poll than like a census. It seems to be far less effective than reaching out to those people, rather than inviting them to participate.

MARK McELROY: But we also have engineers who go and work on the ground in these communities to verify data. We have engineers who challenge our map. In each of these communities where we operate, we form what we call an eCommunity Leadership Team, and we ask questions like, how is this community using technology, how would this community like to use technology? And then we help them make plans for how to get there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is a problem that a lot of your critics cite. You received funding from and are governed by a board of directors that has substantial ties to three of the biggest telecoms - AT&T, Verizon and Comcast. Now, these are the same telecoms that stand to gain from your maps. Doesn't this represent a clear conflict of interest?

MARK McELROY: I could understand how it could be construed as so, but in reality it does not. We relate to more than 300 providers of broadband, and our board also includes some of the most respected consumer advocacy groups in the country. If our programs and solutions are not relevant and formed by the largest and the smallest kind of providers, then it’s not going to be as relevant as it needs to be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, I get that. You have an inclusive board. But wouldn't it be much better if all those companies, large and small, participated in a government- or state-sponsored mapping program, instead of one that was sponsored by an organization like yours that gets most of its money from the business it’s supposed to be mapping?

MARK McELROY: It’s a security issue. Just a few weeks ago in Silicon Valley – I think it was San Jose – the telecommunication infrastructure was sabotaged and, you know, there were tens of thousands without telecommunication services. Think about the kind of interruption of our [LAUGHS] daily life that we all enjoy, if we had a sudden loss of that kind of connectivity. What we do when we collect and publish the data in these maps is we publish everything about a broadband’s availability. What we don't publish are identifiers of where the infrastructure is actually in the ground, for example, for the wire lines.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So you’re saying that allowing the government to take over this would present a palpable national security risk to our interconnectedness? The government can't keep a secret?

MARK McELROY: Exactly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] All right [LAUGHS], because I was just going to say that I understand that there are non-disclosure agreements that restrict what the public can find out about where these facilities are that are so vulnerable, but they also can't find out about your process or your operation. And so, the question is, is why should you receive state or federal funds, if you insist on being opaque on these non-security issues?

MARK McELROY: Our maps are very transparent. Anyone can log into any of the websites where our maps are hosted. They can find, down to the most granular level, who can and cannot access broadband within a given community, at a given address.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What information, aside from the location of certain sensitive bits of infrastructure, are you keeping off these maps, and why?

MARK McELROY: There is no other information.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Everything else about your operation is entirely out there.

MARK McELROY: Everything else that we collect is made public.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You've been working on this for about five years. Can you tell me how materially these maps have helped to close the digital divide?

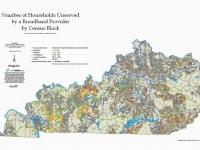

MARK McELROY: Sure. The model that we implement in other states grew out of our experience in the State of Kentucky. When we started, 60 percent of households could access broadband in Kentucky. By producing the first broadband map, by simply making it clear where the service wasn't, in about a three-year process, Kentucky went from that 60 percent availability to around a 95 percent availability figure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mark, thank you very much.

MARK McELROY: Brooke, thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mark McElroy is Connected Nation’s senior vice president of communications. Art Brodsky is the communications director for Public Knowledge, a consumer advocacy group that has some serious issues with Connected Nation, starting with its mapping methodology.

ART BRODSKY: The assumption they make is everyone within a three-mile radius of a telephone central office, for example, or a cell tower or a cable head end, has service, and they don't. I mean, I was talking to a woman in a town in eastern North Carolina a couple of months ago, in the town of Roper. They did their own survey, and they found, for example, that the numbers that a Connected Nation affiliate down there had done were wildly inaccurate. For example, residents within spitting distance of the central office, which should, under the Connected Nation map, have service, didn't. And the problem is that under non-disclosure agreements which Connected Nation uses, none of that data is verifiable. What we need is accurate information to see which neighborhoods, which towns, which parts of neighborhoods and towns are being served and which aren't, and why. This is not just a rural problem, by the way. It’s also an urban problem, because there are parts of cities which have lousy broadband service.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Basically, are you suggesting that it would be in their interest to overcount access so they don't have to go that extra mile?

ART BRODSKY: Or they could be hiding the fact that maybe it’s the more wealthy areas of a service territory that have fiber service or the fastest service where other areas are lagging behind. In the old, old days, with banking, they used to call that redlining, where banks would literally draw a red line around the map and not make loans in a neighborhood. Under a non-disclosure agreement, for example, that Connected Nation uses across the country, their maps can't differentiate between technologies. They can't say, oh, here’s telephone company service or here’s cable service or here’s wireless service in any particular area. Everything they do is confidential.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, Mark McElroy of Connected Nation told me that it keeps information secret to protect the security of their facilities, and that is the only information that they keep secret.

ART BRODSKY: That’s nonsense. I worked with a state legislator in my home state of Maryland to get a broadband mapping bill done a couple of years ago, and the lobbyist for Comcast, the big cable company, came in and used that identical argument, invoking 9/11 and terrorists. The fact of the matter is, you can drive around and see where a telephone company’s central office is. You can see where its cell towers are. That stuff isn't secret. The only group left in the dark are the consumers who are trying to figure out what’s in their neighborhood or a business that’s trying to move to an area that might be dependent on telecommunications.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So who do you think should be doing this mapping?

ART BRODSKY: A mapping project ideally should be directed by a government agency, either federal or state, done by a legitimate mapping company with a history of achievement, not affiliated with any telecommunications provider. There are lots of them out there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, you've criticized the dominance of big carriers on Connected Nation’s governing board. They say that smaller providers also sit on the board, as well as consumer advocates. Is there any way that a company like Connected Nation could have a relationship with the telecom industry and avoid this conflict of interest appearance?

ART BRODSKY: No. A company like Connected Nation shouldn't exist. The whole point of this broadband mapping endeavor is to find out where service is. And if you have the people who control where that service is controlling the data, they can shape it to their best advantage. Connected Nation was started by a Bell South lobbyist in Kentucky. They lobbied for deregulatory legislation in Kentucky. They were clearly on the side of the industry during the legislative battles. This isn't something that they've hidden; this is something they've boasted about.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Connected Nation also told us that what they've done so far has had a significant impact. In a place like Kentucky, they say, usage went up from 60 percent to 95 percent within six to nine months of having created these maps because people knew where they had to expand service.

ART BRODSKY: Yes, and they are the only ones in the state of Kentucky saying that. [BROOKE LAUGHS] And that is the reason that Governor Beshear, when he took office, struck them from the budget entirely, because the state was not getting its money’s worth. In fact, if you look at the numbers, there are two things that are evident. One, Kentucky actually slipped. In every data ranking that you look at, they have gone down since Connected Nation has been there. And, secondly, what they do is take credit for everyone’s service, not just theirs. So if there is a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to a rural telephone company or a loan that helps them improve the service, ConnectKentucky counts it as theirs. If there is a municipal utility which upgrades its service and the folks in, say, Glasgow, Kentucky now have fiber and better broadband service, Connected Nation will claim that as a success.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: All right. Art, thank you very much.

ART BRODSKY: Thank you.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Art Brodsky is the communications director for Public Knowledge.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]