Snap Judgments

Transcript

BOB GARFIELD:

This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Every now and then, photojournalism gives rise to ethical questions. For instance, why was O.J.’s image digitally darkened on the cover of Time? Did tight shots of Saddam’s statue being toppled by Iraqis intentionally obscure the U.S. Marines’ role in the incident? Did newspapers whitewash the horror of war by suppressing images of corpses? Were famous photos from World War I and the Spanish Civil War actually reenactments?

There are clear rules that supposedly govern such situations, sometimes observed, sometimes not. But, as Bob reports, one category of mass media photography operates with hardly any rules at all.

By the way, go to Onthemedia.org to find a slideshow of the photos discussed in this piece.

BOB GARFIELD:

Jill Greenberg is a portrait photographer most famous for a series of pictures of toddlers crying their eyes out. She achieved these hilarious and heartbreaking Kodak moments by giving the kids lollipops, then grabbing the treats away. Okay, maybe it’s a little bit on the cruel side. On the other hand, the kids get over it in about a minute, and the pictures are fabulous. So suck on that one a while.

Meantime, know that Greenberg photographs grownups too, famous ones, on assignment for such publications as Wired, Entertainment Weekly, TV Guide and all three major news magazines.

In September, she was asked by The Atlantic to do a cover portrait of John McCain. Now, it happens that Greenberg despises McCain, so after capturing the heroic poses Atlantic editors were seeking, she coaxed the presidential candidate toward a separate lighting setup where she posed him above a strobe. This gave her the shot she was looking for, one she posted on her website, a diabolical McCain awash in ghastly facial shadows.

Later, Greenberg bragged to the New York Post how easy it had been to trick him, like taking candy from a baby, you might say. Yet, she doesn't quite get why her Atlantic editors and many others flipped out.

JILL GREENBERG:

I do the job that’s asked of me that day, and what I do beyond that is not really anyone’s business. You know, especially when this election was so crucial to me and my family, I just felt, you know, maybe coloring outside the lines this one time wouldn't be such a big deal.

BOB GARFIELD:

Assuming she can locate any line in the first place. The McCain episode was merely the latest to raise ethics questions in portrait photography, chief among them being, are there any? Where is the distinction between artistic prerogative and photo “gotcha”? If a picture is worth a thousand words, who protects the subject - and the audience - from a thousand words manipulated or taken out of context?

The answers reside in the murk of art, journalistic comment, reader expectations and even basic human vanity. But the topic here is potentially corrupting influences, so let's begin with the most obvious, the profit motive. The cover of a magazine is the single biggest determinant of sales.

MARYANNE GOLON:

It’s very much an advertisement for the publication.

BOB GARFIELD:

MaryAnne Golon is former director of photography for Time Magazine.

MARYANNE GOLON:

Once you’re choosing an image, you want the image to be arresting. You want it to stand out in all the media noise on a newsstand.

BOB GARFIELD:

Obviously, newsstand appeal hinges mainly on the subject him- or herself, but that quick newsstand scan is critical. Hence the demand for such distinctive portraitists as Greenberg, Platon, Martin Schoeller, Annie Leibovitz and the late Richard Avedon.

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I think there has been a long tradition in portrait photography where photographers try to capture a person’s personality, rather than feeling obliged in trying to make them look good.

BOB GARFIELD:

Photographer Martin Schoeller:

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

The best example, I think, is Richard Avedon. I mean, you feel like he would take your picture and you would come across as mentally challenged. I don't think Avedon ever tried to please anyone but himself with his portraits.

BOB GARFIELD:

Nor Schoeller himself. His ultratight portraits, which have appeared in such publications as Rolling Stone and The New Yorker, are typically grim mug shots, sort of Chuck Close meets your driver’s license photo. His Jack Nicholson could be a serial rapist, and his Barack Obama resembles Abraham Lincoln, homely wart and all.

The shots are arty and arresting but not exactly flattering, although Schoeller takes issue with that characterization.

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I don't think my pictures are unflattering, to be honest. The light is very flattering. It’s not a wide-angle lens; they're not distorted. I just think that people are nowadays not used to seeing people as people anymore, and your perception of the environment is so twisted by all these pictures that you see in magazines and advertisements that if you see a person just for who they are, you are really shocked.

BOB GARFIELD:

Are we indeed so conditioned to the unreal world of ads and celebrity photography that we, the audience, can't handle the truth? Certainly, magazine photography, at least where movie stars aren't involved, is not hagiography. It is not commissioned to flatter the subject. But whether you’re JFK sitting for Karsh of Ottawa or the family next door posing in sweaters at Olan Mills, no one wants to look mentally challenged or criminal, or demonic, or even unattractive.

So do portraitists and editors have any responsibility to their subjects’ basic vanity? Reporters certainly don't. If the reporting doesn't distort facts or context, nobody has a beef. Why should photography be held to a different standard?

PLATON:

All I can do is to try and find a human quality -

BOB GARFIELD:

This is the photographer, Platon.

PLATON:

- and break through all of these plastic walls that are put up in front of me and my sitter, and all the time restrictions and all the pressure that they try to bombard me with to stop me finding perhaps my sense of what the truth is.

BOB GARFIELD:

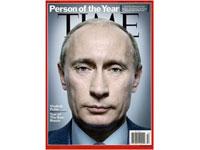

Platon shot the famous Esquire photo of Bill Clinton, cat-who-ate-the-canary grin on his face, hands on his knees and necktie, like the arrow of Eros, pointing to his notorious crotch. Platon has also famously crafted portraits of a menacing Barry Bonds, Karl Rove cowled in a sinister black aura and a sepulchral Vladimir Putin.

Platon believes it is loathsome to use digital or darkroom tricks to distort somebody’s likeness, but he’s cool with whatever actually happens at the shoot, such as his April, 2005 Ann Coulter photo on the cover of Time Magazine. The incendiary right-wing author was shot from almost floor level with a wide-angle lens, filling the foreground with her optically elongated legs. I can tell you, this is the one and only time I personally felt sympathy for Ann Coulter. She looked like a blonde praying mantis. Platon:

PLATON:

She’s very tall, very, very slim, very skinny, and she’s got these massive long legs. I mean, sure, there is a distortion perhaps of perspective, but this is really how I see her. I was probably a few inches away from her toes when I was taking the picture, so for her to be slightly smiling at me and leaning forward, she knows what’s going on.

BOB GARFIELD:

But did she know the effect of the wide lens?

PLATON:

Well, I mean, look, everybody now in the business [LAUGHS] seems to know the way I see the world. I want to pull people out of their reality and into our reality.

BOB GARFIELD:

Out of her reality, how he sees her, what his truth is. Is that a confession or a mission statement? Time’s MaryAnne Golon was on the set that day, and she thinks the latter. The crux of the matter, she believes, is artistic interpretation.

MARYANNE GOLON:

I mean, if someone is a public figure and you subject them to any sort of representation – it could be a political cartoon, it could be an artist illustration, it could be a photographer – there’s going to be an interpretation of that person.

BOB GARFIELD:

And for the very reason that people are vain and self-conscious, trying to define their own interpretation of themselves for the lens, they sometimes need to be nudged or prodded or even manipulated into revealing something of themselves, such as when Yousuf Karsh pulled the cigar from Winston Churchill’s mouth – like candy from a baby – and triggered portraiture’s most famous scowl.

MARYANNE GOLON:

And should the photographer not have done that? I'd say, no, of course, the photographer should have yanked the cigar [LAUGHS] out of his mouth because it was a fantastic, reflective, important portrait of an important person, at an important time. And I would pretty much hold the same for Ann Coulter and the image Platon did.

BOB GARFIELD:

Fair enough, although let the record reflect that after Platon pulled Coulter from her reality to his, Golon got a call from her own mother who thought Coulter looked like a spider.

In photography, this reality thing is hard to pin down. Each of a sitting’s dozens or hundreds of shots is a frozen two-dimensional representation of a living, moving, three-dimensional being, a laser-sliced instant, invisible in real time. It may be a reasonable likeness, it may express some aspect of mood or personality, but it is, by definition, out of context, altered by angle, lighting and optics. Platon:

PLATON:

It’s such a strange artistic process that it’s very difficult to express in words. I mean, you could say that I'm a disturber or I'm a professional outsider, and I come in and try to disturb the status quo.

BOB GARFIELD:

In purely artistic terms, such sentiments are unassailable, but if a magazine writer marched into a profile interview with the announced intention of cajoling from a subject a single word or phrase that would be the sole focus of the profile, well, that’s pretty much the definition of gotcha journalism. Is creating a disturbance ever a reasonable journalistic technique?

PLATON:

To be quite honest, I'm often surprised that I'm allowed to carry on doing what I do every day. But I haven't been stopped yet, and I'm still waiting to be sent out of the country for bad photographic behavior.

BOB GARFIELD:

Not likely. Platon is prized by editors, for the same reason he is shocking to readers. He plays havoc with our expectations, expectations so obsessively reinforced by Hollywood and Madison Avenue that we've all been, in Platon’s words, “sedated with perfection.”

You may recall Schoeller saying much the same. In magazine photography circles, this is a steady refrain. Here’s Maer Roshan, founder and editor-in-chief of the recently-defunct Radar Magazine.

MAER ROSHAN:

You look at any Hollywood celebrity, half of your time is spent wrangling over what they will wear. Some of them demand final photo approval. They demand certain photographers. Hollywood celebrities have a lot of power over how they're depicted in magazine covers.

BOB GARFIELD:

A New York Times piece last weekend described, for instance, Angelina Jolie’s demands not only for photo approval from People Magazine but also promises about reportage in exchange for baby pictures.

For self-respecting photographers and editors, that stuff is frustrating and humiliating. And one after another, they describe the impulse to assert independence. It comes up [LAUGHS] so often, you have to wonder, when a subject without the leverage to call the shots gets stung, is that entirely independence or also backlash?

Consider Radar’s September cover piece, titled What’s So Scary About Michelle Obama? Plucked to illustrate it, from the rolls and rolls of shots of a smiling future First Lady, was one moment when she stared blankly at the camera, her arms folded across her chest – the angry black woman, herself.

Now, the story was precisely about confronting that stereotype, so the cover photo could be justified on pertinence alone. But Obama felt hoodwinked, a fate Angelina Jolie need not fear. Is that fair?

Well, maybe it is. One argument goes that a photo subject, by agreeing to the shoot, assumes all risks. Jill Greenberg:

JILL GREENBERG:

You know, maybe Ann Coulter doesn't have a publicist from a great agency that is good at protecting her. But when somebody signs up for a cover photo shoot, they're doing it for their own best interest; they're doing it for their own P.R. And, you know, you have to be careful. You don't know what the story’s going to be. I mean -

BOB GARFIELD:

Caveat emptor.

JILL GREENBERG:

Exactly. It’s a gamble.

BOB GARFIELD:

Wow. Media roulette. You pays your money and you takes your chances. Moreover, Greenberg says, the wheel is sometimes rigged.

JILL GREENBERG:

I've been assigned by magazine editors to make people look bad. You know, I've been assigned to trick my subject by magazine editors. It’s just really strange. I mean, people just don't actually know the way things are.

BOB GARFIELD:

Greenberg declined to provide details or to name names, so let's just hope premeditated photo hatchet jobs are rare. But if they aren't, how could we be surprised? When it comes to ethics or canons of conduct, the lines, if they even exist, are maddeningly out of focus.

JILL GREENBERG:

I went to art school, so I don't know what those canons and ethics are.

BOB GARFIELD:

Nor is she, by any means, alone. I asked Martin Schoeller - is there a standard of basic fairness, for example?

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I think this varies greatly from photographer to photographer. Yeah. No, I guess no [LAUGHS] is the answer.

BOB GARFIELD:

No. Schoeller hasn't gotten the memo, Greenberg hasn't gotten the memo, because the memo has yet to be written. High time, I'd say, not because these issues are black and white, but because they obviously aren't.

This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Every now and then, photojournalism gives rise to ethical questions. For instance, why was O.J.’s image digitally darkened on the cover of Time? Did tight shots of Saddam’s statue being toppled by Iraqis intentionally obscure the U.S. Marines’ role in the incident? Did newspapers whitewash the horror of war by suppressing images of corpses? Were famous photos from World War I and the Spanish Civil War actually reenactments?

There are clear rules that supposedly govern such situations, sometimes observed, sometimes not. But, as Bob reports, one category of mass media photography operates with hardly any rules at all.

By the way, go to Onthemedia.org to find a slideshow of the photos discussed in this piece.

BOB GARFIELD:

Jill Greenberg is a portrait photographer most famous for a series of pictures of toddlers crying their eyes out. She achieved these hilarious and heartbreaking Kodak moments by giving the kids lollipops, then grabbing the treats away. Okay, maybe it’s a little bit on the cruel side. On the other hand, the kids get over it in about a minute, and the pictures are fabulous. So suck on that one a while.

Meantime, know that Greenberg photographs grownups too, famous ones, on assignment for such publications as Wired, Entertainment Weekly, TV Guide and all three major news magazines.

In September, she was asked by The Atlantic to do a cover portrait of John McCain. Now, it happens that Greenberg despises McCain, so after capturing the heroic poses Atlantic editors were seeking, she coaxed the presidential candidate toward a separate lighting setup where she posed him above a strobe. This gave her the shot she was looking for, one she posted on her website, a diabolical McCain awash in ghastly facial shadows.

Later, Greenberg bragged to the New York Post how easy it had been to trick him, like taking candy from a baby, you might say. Yet, she doesn't quite get why her Atlantic editors and many others flipped out.

JILL GREENBERG:

I do the job that’s asked of me that day, and what I do beyond that is not really anyone’s business. You know, especially when this election was so crucial to me and my family, I just felt, you know, maybe coloring outside the lines this one time wouldn't be such a big deal.

BOB GARFIELD:

Assuming she can locate any line in the first place. The McCain episode was merely the latest to raise ethics questions in portrait photography, chief among them being, are there any? Where is the distinction between artistic prerogative and photo “gotcha”? If a picture is worth a thousand words, who protects the subject - and the audience - from a thousand words manipulated or taken out of context?

The answers reside in the murk of art, journalistic comment, reader expectations and even basic human vanity. But the topic here is potentially corrupting influences, so let's begin with the most obvious, the profit motive. The cover of a magazine is the single biggest determinant of sales.

MARYANNE GOLON:

It’s very much an advertisement for the publication.

BOB GARFIELD:

MaryAnne Golon is former director of photography for Time Magazine.

MARYANNE GOLON:

Once you’re choosing an image, you want the image to be arresting. You want it to stand out in all the media noise on a newsstand.

BOB GARFIELD:

Obviously, newsstand appeal hinges mainly on the subject him- or herself, but that quick newsstand scan is critical. Hence the demand for such distinctive portraitists as Greenberg, Platon, Martin Schoeller, Annie Leibovitz and the late Richard Avedon.

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I think there has been a long tradition in portrait photography where photographers try to capture a person’s personality, rather than feeling obliged in trying to make them look good.

BOB GARFIELD:

Photographer Martin Schoeller:

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

The best example, I think, is Richard Avedon. I mean, you feel like he would take your picture and you would come across as mentally challenged. I don't think Avedon ever tried to please anyone but himself with his portraits.

BOB GARFIELD:

Nor Schoeller himself. His ultratight portraits, which have appeared in such publications as Rolling Stone and The New Yorker, are typically grim mug shots, sort of Chuck Close meets your driver’s license photo. His Jack Nicholson could be a serial rapist, and his Barack Obama resembles Abraham Lincoln, homely wart and all.

The shots are arty and arresting but not exactly flattering, although Schoeller takes issue with that characterization.

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I don't think my pictures are unflattering, to be honest. The light is very flattering. It’s not a wide-angle lens; they're not distorted. I just think that people are nowadays not used to seeing people as people anymore, and your perception of the environment is so twisted by all these pictures that you see in magazines and advertisements that if you see a person just for who they are, you are really shocked.

BOB GARFIELD:

Are we indeed so conditioned to the unreal world of ads and celebrity photography that we, the audience, can't handle the truth? Certainly, magazine photography, at least where movie stars aren't involved, is not hagiography. It is not commissioned to flatter the subject. But whether you’re JFK sitting for Karsh of Ottawa or the family next door posing in sweaters at Olan Mills, no one wants to look mentally challenged or criminal, or demonic, or even unattractive.

So do portraitists and editors have any responsibility to their subjects’ basic vanity? Reporters certainly don't. If the reporting doesn't distort facts or context, nobody has a beef. Why should photography be held to a different standard?

PLATON:

All I can do is to try and find a human quality -

BOB GARFIELD:

This is the photographer, Platon.

PLATON:

- and break through all of these plastic walls that are put up in front of me and my sitter, and all the time restrictions and all the pressure that they try to bombard me with to stop me finding perhaps my sense of what the truth is.

BOB GARFIELD:

Platon shot the famous Esquire photo of Bill Clinton, cat-who-ate-the-canary grin on his face, hands on his knees and necktie, like the arrow of Eros, pointing to his notorious crotch. Platon has also famously crafted portraits of a menacing Barry Bonds, Karl Rove cowled in a sinister black aura and a sepulchral Vladimir Putin.

Platon believes it is loathsome to use digital or darkroom tricks to distort somebody’s likeness, but he’s cool with whatever actually happens at the shoot, such as his April, 2005 Ann Coulter photo on the cover of Time Magazine. The incendiary right-wing author was shot from almost floor level with a wide-angle lens, filling the foreground with her optically elongated legs. I can tell you, this is the one and only time I personally felt sympathy for Ann Coulter. She looked like a blonde praying mantis. Platon:

PLATON:

She’s very tall, very, very slim, very skinny, and she’s got these massive long legs. I mean, sure, there is a distortion perhaps of perspective, but this is really how I see her. I was probably a few inches away from her toes when I was taking the picture, so for her to be slightly smiling at me and leaning forward, she knows what’s going on.

BOB GARFIELD:

But did she know the effect of the wide lens?

PLATON:

Well, I mean, look, everybody now in the business [LAUGHS] seems to know the way I see the world. I want to pull people out of their reality and into our reality.

BOB GARFIELD:

Out of her reality, how he sees her, what his truth is. Is that a confession or a mission statement? Time’s MaryAnne Golon was on the set that day, and she thinks the latter. The crux of the matter, she believes, is artistic interpretation.

MARYANNE GOLON:

I mean, if someone is a public figure and you subject them to any sort of representation – it could be a political cartoon, it could be an artist illustration, it could be a photographer – there’s going to be an interpretation of that person.

BOB GARFIELD:

And for the very reason that people are vain and self-conscious, trying to define their own interpretation of themselves for the lens, they sometimes need to be nudged or prodded or even manipulated into revealing something of themselves, such as when Yousuf Karsh pulled the cigar from Winston Churchill’s mouth – like candy from a baby – and triggered portraiture’s most famous scowl.

MARYANNE GOLON:

And should the photographer not have done that? I'd say, no, of course, the photographer should have yanked the cigar [LAUGHS] out of his mouth because it was a fantastic, reflective, important portrait of an important person, at an important time. And I would pretty much hold the same for Ann Coulter and the image Platon did.

BOB GARFIELD:

Fair enough, although let the record reflect that after Platon pulled Coulter from her reality to his, Golon got a call from her own mother who thought Coulter looked like a spider.

In photography, this reality thing is hard to pin down. Each of a sitting’s dozens or hundreds of shots is a frozen two-dimensional representation of a living, moving, three-dimensional being, a laser-sliced instant, invisible in real time. It may be a reasonable likeness, it may express some aspect of mood or personality, but it is, by definition, out of context, altered by angle, lighting and optics. Platon:

PLATON:

It’s such a strange artistic process that it’s very difficult to express in words. I mean, you could say that I'm a disturber or I'm a professional outsider, and I come in and try to disturb the status quo.

BOB GARFIELD:

In purely artistic terms, such sentiments are unassailable, but if a magazine writer marched into a profile interview with the announced intention of cajoling from a subject a single word or phrase that would be the sole focus of the profile, well, that’s pretty much the definition of gotcha journalism. Is creating a disturbance ever a reasonable journalistic technique?

PLATON:

To be quite honest, I'm often surprised that I'm allowed to carry on doing what I do every day. But I haven't been stopped yet, and I'm still waiting to be sent out of the country for bad photographic behavior.

BOB GARFIELD:

Not likely. Platon is prized by editors, for the same reason he is shocking to readers. He plays havoc with our expectations, expectations so obsessively reinforced by Hollywood and Madison Avenue that we've all been, in Platon’s words, “sedated with perfection.”

You may recall Schoeller saying much the same. In magazine photography circles, this is a steady refrain. Here’s Maer Roshan, founder and editor-in-chief of the recently-defunct Radar Magazine.

MAER ROSHAN:

You look at any Hollywood celebrity, half of your time is spent wrangling over what they will wear. Some of them demand final photo approval. They demand certain photographers. Hollywood celebrities have a lot of power over how they're depicted in magazine covers.

BOB GARFIELD:

A New York Times piece last weekend described, for instance, Angelina Jolie’s demands not only for photo approval from People Magazine but also promises about reportage in exchange for baby pictures.

For self-respecting photographers and editors, that stuff is frustrating and humiliating. And one after another, they describe the impulse to assert independence. It comes up [LAUGHS] so often, you have to wonder, when a subject without the leverage to call the shots gets stung, is that entirely independence or also backlash?

Consider Radar’s September cover piece, titled What’s So Scary About Michelle Obama? Plucked to illustrate it, from the rolls and rolls of shots of a smiling future First Lady, was one moment when she stared blankly at the camera, her arms folded across her chest – the angry black woman, herself.

Now, the story was precisely about confronting that stereotype, so the cover photo could be justified on pertinence alone. But Obama felt hoodwinked, a fate Angelina Jolie need not fear. Is that fair?

Well, maybe it is. One argument goes that a photo subject, by agreeing to the shoot, assumes all risks. Jill Greenberg:

JILL GREENBERG:

You know, maybe Ann Coulter doesn't have a publicist from a great agency that is good at protecting her. But when somebody signs up for a cover photo shoot, they're doing it for their own best interest; they're doing it for their own P.R. And, you know, you have to be careful. You don't know what the story’s going to be. I mean -

BOB GARFIELD:

Caveat emptor.

JILL GREENBERG:

Exactly. It’s a gamble.

BOB GARFIELD:

Wow. Media roulette. You pays your money and you takes your chances. Moreover, Greenberg says, the wheel is sometimes rigged.

JILL GREENBERG:

I've been assigned by magazine editors to make people look bad. You know, I've been assigned to trick my subject by magazine editors. It’s just really strange. I mean, people just don't actually know the way things are.

BOB GARFIELD:

Greenberg declined to provide details or to name names, so let's just hope premeditated photo hatchet jobs are rare. But if they aren't, how could we be surprised? When it comes to ethics or canons of conduct, the lines, if they even exist, are maddeningly out of focus.

JILL GREENBERG:

I went to art school, so I don't know what those canons and ethics are.

BOB GARFIELD:

Nor is she, by any means, alone. I asked Martin Schoeller - is there a standard of basic fairness, for example?

MARTIN SCHOELLER:

I think this varies greatly from photographer to photographer. Yeah. No, I guess no [LAUGHS] is the answer.

BOB GARFIELD:

No. Schoeller hasn't gotten the memo, Greenberg hasn't gotten the memo, because the memo has yet to be written. High time, I'd say, not because these issues are black and white, but because they obviously aren't.