Transcript

BOB GARFIELD:

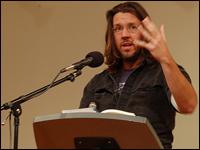

Author David Foster Wallace died last Friday at the age of 46. He was best known as a fiction writer who made his reputation with the 1,079-page novel Infinite Jest, a dizzying cocktail of plots and asides that was funny, sad and wise in equal measure.

But Wallace also was a journalist, reporting on subjects ranging from wind patterns to porn awards. This is Wallace reading a piece he wrote for Harper’s about a luxury cruise where there were 11 [LAUGHS] opportunities a day for meals.

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE:

Tex-Mex night out by the pools featured what must have been a seven-foot-high ice sculpture of Pancho Villa -

[LAUGHTER]

- that spent the whole party dripping steadily out of the mammoth sombrero of Tibore, Table 64’s beloved and extremely cool Hungarian waiter, whose contract forces him on Tex-Mex night to wear a serape and a straw sombrero with a 17-inch radius, and to dispense four-alarm chili from a steam table placed right underneath an ice sculpture -

[LAUGHTER]

- and whose pink and bird-like face on occasions like this expressed a combination of mortification and dignity that seemed somehow to sum up the whole plight of post-war Eastern Europe.

[LAUGHTER]

BOB GARFIELD:

Kathleen Fitzpatrick is an associate professor of media studies and literature at Pomona College, and she joins us now to talk about her late colleague. Kathleen, welcome to On the Media.

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Thank you very much.

BOB GARFIELD:

I must confess that until this week I'd never read a single word of David Foster Wallace’s work because he’s reputed as a novelist to be very dense and difficult, along Thomas Pynchon/James Joyce lines, and I didn't even know he did journalism.

But in preparation [LAUGHS] for this conversation, I've been reading his reporting pieces, and they are simply magnificent – crystal clear and fact filled. Was he like two writers in one body?

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

No, actually, I mean, my sense was always that the fiction and the nonfiction were very much of a piece, that he was interested in getting at something that was unspoken at the heart of American culture, whether it was looking at these bizarre phenomena like conservative talk radio or like the luxury cruise ship or like the state fair, and attempting to figure out what these phenomena said, in the same way that in Infinite Jest the nexus of tennis and rehab and the American media says something about a kind of loneliness and despair at the heart of American culture today.

BOB GARFIELD:

I was expecting him to be very writerly, but exactly the opposite. The operative word would seem to be clarity. How did he acquire the rep as being difficult in the first place?

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Well, there’re a number of different ways that this came about - for instance, the essay, Host, which is about conservative talk radio host John Ziegler, which has an inordinate number of footnotes and annotations, and annotations that are themselves annotated, using what was a really [LAUGHS] remarkable vocabulary.

There is a way in which he gets accused of a kind of smarty-pantsness, right? But I think what gets missed in those accusations is the heart that is underneath it. He gets an assignment, for instance, to go write an essay about the Maine Lobster Festival, and instead they get this long meditation on the ethics of lobster consumption.

BOB GARFIELD:

And whether a lobster feels pain, whether it’s a sentient beast -

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Right.

BOB GARFIELD:

- which has hitherto probably never been considered in gourmet magazines. [LAUGHS]

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Oh well, certainly not, and produced infuriated responses from the subscribers to the magazine.

BOB GARFIELD:

One of Wallace’s longest pieces was about accompanying John McCain on his presidential campaign tour eight years ago, in 2000.

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Yes.

BOB GARFIELD:

What was curious about that exercise is that instead of spending his time with the spinners and the campaign aides, he relied on the observations of the news crew cameramen, who were -

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Right.

BOB GARFIELD:

- shooting the footage. What was that all about?

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

He was repeatedly, in his essays, fascinated by what he referred to in his essay on Television and U.S. Fiction as “the culture of watching” – right? The people doing the watching, the cameramen, the ones who aren't part of the spectacle are the ones who, for him, have the greatest insight into what’s going on.

So again, you have this moment in which an assignment to write about the McCain campaign and its impact in the 2000 election instead becomes an opportunity for him really to muse on the relationship between the media and the ways it functions and American electoral politics in a way that gets at something about the rather desperate state of contemporary civic life.

BOB GARFIELD:

We spoke to his editor at Harper’s Magazine, Colin Harrison, who assigned him to go on that cruise that we just heard him read about, in the piece Wallace titled, A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again.

Harrison said that reading the piece for the first time was like “a comet going by your head at ground level.” Do you know of any other journalists, long-form journalists, whizzing like comets these days?

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

I mean, there are many brilliant journalists out there, but I don't know that anyone brings together that same kind of pyrotechnic brilliance with the very clear ethical and moral concerns that underwrite all of the work that he did.

BOB GARFIELD:

Kathleen, thank you very much.

KATHLEEN FITZPATRICK:

Thank you very much.

BOB GARFIELD:

Kathleen Fitzpatrick is an associate professor of media studies and literature at Pomona College. She has taught about and with the late David Foster Wallace.