Transcript

KERRY NOLAN:

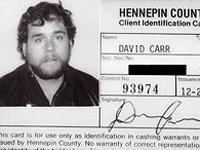

For New York Times reporter David Carr, it was the story of a lifetime, a hard charging reporter who built a career chasing complicated stories, working his way up to a position at The New York Times, all while doing a tremendous number of drugs and living the kind of reprehensible lifestyle that would make for a lurid, depressing series on utter self‑destruction.

The story, of course, is Carr's own, and a few years ago he set out to tell it himself. Knowing full well that he was his most unreliable witness, he brought the rigor of journalism to his own memoir, and the result is The Night of the Gun. David, welcome back to the show.

DAVID CARR:

Well, it's a pleasure to be with you, Kerry.

KERRY NOLAN:

Now, you concede in the book that the rules that you set out for yourself were kind of a conceit, so can you explain what those rules were?

DAVID CARR:

When an event was described, I tried to go out and triangulate, find other people that saw it, participated in it. I tried to find underlying documents. I tried to correlate photos to different times. There are things I didn't find that I wanted, but I hired two private investigators. They didn't work out very well.

And then I hired a separate reporter who I respected and admired a lot, Don Jacobson, a reporter in Minneapolis. And Don found some things that I couldn't find, and the things that he could not find, I was able to write more confidently that they could not be found because it wasn't just me.

All those things sort of came together with the need to come up with some kind of concept that would make what is an almost sort of generic story of abasement followed by redemption, interesting to the reader. So it was sort of need, skill set, plus gimmick meeting the moment.

KERRY NOLAN:

Were you also just a little bit aware of the James Frey memoir, A Million Little Pieces?

DAVID CARR:

I was more than aware of it. I had done a story about, when he went on Oprah and Oprah tore off his arms and legs in front of millions. And I'd say that made a little bit of an impression on me.

KERRY NOLAN:

[LAUGHS] I'm sure. So, given all of that, why write the book?

DAVID CARR:

I thought I could write a really excellent book. Twenty years ago I was fresh off a ten‑year addiction to cocaine. I was on welfare. I had just gotten custody of my twin baby girls. And I thought to myself, look what happened to me. I was supposedly a hopeless case.

People would ask me, how did that happen? How did that guy become this guy? And I thought it would better to sort of investigate, as opposed to just pontificate.

KERRY NOLAN:

So as a storyteller, apart from the journalistic rigor, did you find that you were kind of forcing yourself to reveal the most lurid details? Was that serving your story?

DAVID CARR:

I came across things, moments in interviews and episodes, that I really didn't even want to share with my wife, to be honest. And when it came time to write the book, I ended up looking at that stuff and I thought, you know, if I shave a single corner so it feels better to me, then the whole thing will sort of fall apart.

And so I just said, I am writing this book about another person, and I want it to be fair and I want everything to be in context, but I don't want to bathe it in pathos. I don't want to explain or excuse. I want to relate what happened as straightforwardly as I can. So that's one thing to write that.

But then you put it out there and you turn into that guy. And that's where I am right not. My story changed when I reported it but it also changed when I wrote it.

KERRY NOLAN:

Let's talk a little about when you were using and you were working. And, you know, you say how in Minnesota, you tried to keep your arrests and crime reporting separate.

DAVID CARR:

Usually a good policy, I would say.

KERRY NOLAN:

[LAUGHS] Was there any upside to skating in those two parallel worlds at the same time?

DAVID CARR:

Well, it certainly wasn't worth what it cost me in terms of human dignity and violence against others. But in terms of what I learned from those days, I'm not really afraid of that much. And that means if I have to go on a media interview and talk about my book, I'm not going to be that worried about that.

And the other thing is, there are gangsters in all walks of life, and some of them wear pinstripes and some of them wish to intimidate and lay you low. And I feel I can do a real actual threat assessment when I'm with someone and suss out whether they can really do me harm. And that's, I guess, one of the few gifts of, you know, a really wayward history.

KERRY NOLAN:

When an excerpt from your book appeared in The New York Times Magazine a few weeks ago, a lot of people wondered in the online comments, why they should ever trust you again, that addicts are inherently liars ‑ and hopefully journalists aren't.

So having laid it all out in book form for us, why should we trust you?

DAVID CARR:

You show me where one of my stories ever came up bad. And I don't care when it was from in my career, what it was about, who I was doing. This is not a story about journalistic pathology - nothing of the kind.

I work at The New York Times. I'm proud of the principles we have in common. I've displayed none of the pathology that has occasionally infected journalism, and the proof is in the pudding week after week after week.

The matter of trustworthiness, if you go within the four corners of the book, I don't really ask the reader to trust me. All the documentation is baked in. The witness of others is there. Just in case that doesn't do it for you, there's a website where much of my reporting is up there for inspection.

There is a transparency that should give it some sense of verisimilitude. Doesn't mean every word is true - does not. Like all human endeavors, it's subject to shortages of either attention or effort.

It just means that it was as true as I can make it. And if I thought I was going to be imperiling my reputation as a journalist, I probably wouldn't have done the book.

KERRY NOLAN:

You've been writing about media and celebrities for a while now. How cynical are you about the role that these redemption narratives play in our culture?

DAVID CARR:

Not one little bit. When I did that magazine article, I got 1200 emails. At least half of them were from people either seeking or seeking on behalf of others, some route out of the prison that addiction, 20, 30, 40 million Americans live in. Now, I'm not saying I have any expertise in that regard. I obviously have had my own struggles.

I have some cynicism, I guess, about the commercial aspects of it. I think that there was probably some cynicism in the conception of the book in terms of, if I took this and this and put it together, maybe there'd be a market for that. But I don't think, in the main, that it was a cynical endeavor. If it was, it would have been a very different book.

KERRY NOLAN:

Is it cynical to think that the presumed success of this book is going to change your process of getting stories, of getting people to open up to you?

DAVID CARR:

Really worried about that. You know, I got to The New York Times and I had never worked at a daily, so I was really determined to fit in. And I did a really good job, four or five years of fitting in, and now I'm in the business of sticking out and there's a real standard at the place.

So many people do magnificent things, and you would never know their name. And I'm no longer one of those people. I don't just get in the boat and row. I'm always going to be that guy, so the elevator ride at the place is going to be different.

And now I opened up, you know, my browser on Monday and I was just terrified I was going to see my mug one more time. You know, that guy, I don't know about anybody else, but I'm totally sick of seeing, you know, see the man who stuck things up his nose.

And I opened it up, and, of course, there I was, but it was for a column I wrote about the New Jersey Star‑Ledger. And I tell you, my heart just burst, because I don't plan on writing about myself the rest of my life. I plan on doing what most journalists do, which is finding people more interesting than me, putting a microphone to them, finding out their stories and telling them. And if I ding that, if I damage that, and I think that there's a chance of that - that would be really sad for me.

KERRY NOLAN:

David Carr, thank you so much for being with us.

DAVID CARR:

Pleasure.

KERRY NOLAN:

David Carr is a media columnist for The New York Times and author of Night of the Gun.