Transcript

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Last month, the International Court of Justice in The Hague cleared the Serbian state of inciting genocide against Bosnian Muslims in the mid-'90s. The ruling stated that there was insufficient evidence of, quote, "specific intent on the part of the perpetrators to destroy, in whole or in part, the Bosnian Muslims as such."

The word "genocide" was coined in 1943 by Polish legal scholar Raphael Lemkin, partly because there was no word that could convey the scale of the Turkish massacre of more than a million Armenians in the First World War. In 1948, the U.N. defined "genocide" as "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.

Currently, the head of the European Union is seeking to make genocide denial a crime. Brendan O'Neill edits the British online journal Spiked. He opposes most modern invocations of the word and says that banning genocide denial would squelch both historical research and legitimate dissent.

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

I mean, I keep thinking back to 1999, when it was widely claimed in Europe and in America that there was a genocide occurring in Kosovo. And some of us who were opposed to the bombing of Kosovo on the grounds that it was a barbaric act which would kill civilians, as, indeed, it did, because we said this is not a genocide, we were widely accused of being genocide deniers in the press and by politicians and so on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Now, it seems to me that you object to the word being overused in its purely legal sense, and you also object to it being used in a colloquial way to describe any widespread brutal massacre. When do you think it ought to be used?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

I would only use the word "genocide" to describe what the Nazis did. And I realize that's a controversial view, but I think it's important to understand that is the one instance where the evidence is insurmountable. You just cannot deny, no one can deny, unless they're a crazy anti-Semitic crank, that there was a plan to exterminate an entire group of people and that it almost was successful.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

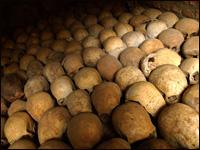

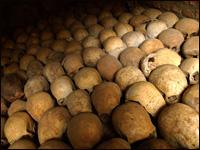

Obviously there's been debate over whether Kosovo, and now Darfur, are really genocides by the classic definition. On the other hand, Rwanda, where there are many people on the record saying that they wanted to wipe out a particular ethnicity right down to every man, woman and child, was a genocide. Wouldn't you agree?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

Well, Rwanda is a different case, but I think even here we need to be quite careful because when people refer to it as a genocide, what they often mean is that it was senseless savagery. It was Dark Continent massacres. We de-contextualize the conflict when we discuss it in those ways.

For example, we overlook the role of the Western powers, not only in standing by while Rwanda occurred, which is the main criticism aimed at them, but also their role in stoking up the conflict. We know that the French backed the Rwandan parties. We know that the Americans and the British trained and supported the RPF inside Uganda for many years.

And I think we have to try to get away from this kind of contemporary view of African conflicts in particular as being inexplicable and just pure savagery, which I think is a borderline racist view.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Now, an international coalition of rights groups and celebrities, called "Save Darfur," is working to draw attention to what it calls the genocide there. Anything wrong with that?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

I think the Save Darfur Coalition is doing great damage, because the attempt of the Save Darfur Coalition to describe Darfurian rebels as the victims of genocide has encouraged those groups to hold back from signing up to peace deals. Because when every Western liberal gives their support to the Darfurian rebels, who are actually quite weak, it bolsters their standing and it makes them hold out.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

The Turks were accused of committing genocide against the Armenians in 1915. Whether or not you believe that charge, it has become an enormous political issue right now, hasn't it?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

Yes, absolutely. And I think this really cuts to the problem with the politicization of genocide. France, last year, took the bizarre step of outlawing denial of the Armenian genocide inside France. France is very skeptical about allowing Turkey into the European Union because it considers it to be a slightly strange Eastern, almost Asian, state.

They're also worried about Turkey joining the EU because of Turkey's close relationship with America. And I think there is something really patronizing in the way in which the contemporary Turkish government is being chastised by various European authorities and basically is being forced to accept that the earlier Turkish government committed a genocide against the Armenians, before it will be allowed to become a member of the civilized club.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Is it a million-and-a-half people who died in the massacre, if you want to call it that, or the genocide, against the Armenians in 1915?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

The usual figures put forward are 1 million or 1.5 million.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Don't you worry about being accused of diminishing that enormous suffering?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

Yes, I do. [LAUGHS] I do worry about that. And it's not my intention at all to diminish the barbarism of what Turkey did to the Armenians in 1915. There is no doubt that it was one of the worst massacres in modern history.

But it's not proven beyond a reasonable doubt that it was a genocide, in the sense that there was a concerted attempt by the Turkish authorities to destroy every single Armenian. That in itself distinguishes it from the Nazi genocide. The aim of the Nazi genocide was to kill every single Jew on the planet and not to leave a single one left.

So I don't want to diminish it, but I do think there is a legitimate debate to be had about whether it was a genocide, or whether it was a hugely horrific massacre.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Some have persuasively argued that using the word "genocide" directs attention to a region that would otherwise be ignored. Isn't it a weapon worth having and using?

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

You're right. It is used as a weapon. And as an anti-imperialist, that's something that worries me greatly, the way in which genocide is now part of the Western armory in its demonization of the Third World.

And if we allow Western powers to use the accusation of genocide to justify their interventions, then we're doing two things. Firstly, we are complicit in the prostitution of the word "genocide" to justify Western domination of the Third World, and secondly, we are encouraging interventions which historically have made conflicts worse rather than better.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Brendan, thank you very much.

BRENDAN O'NEILL:

Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

Brendan O'Neill is editor of the British online magazine Spiked. His column, Pimp my Genocide, can be found at spiked-online.com.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE:

This is On the Media from NPR.