Debunking Myths About the Writers' Strike

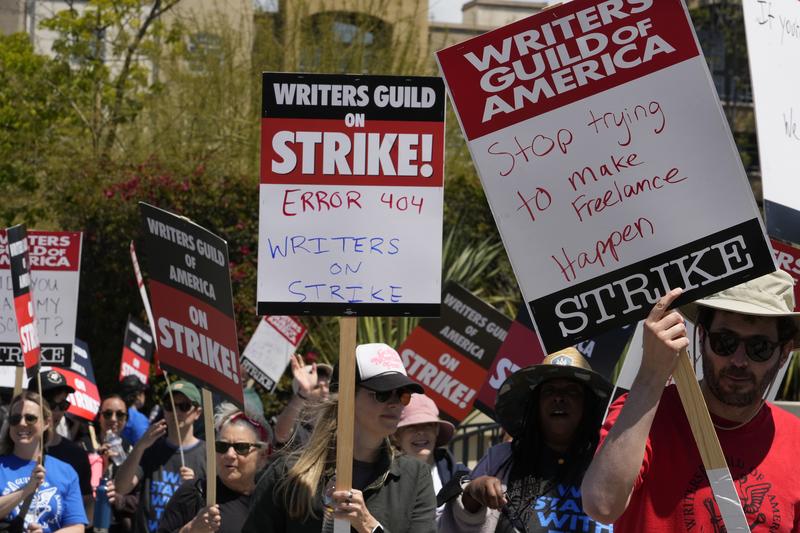

( Damian Dovarganes / AP Images )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media's midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. On Tuesday, we entered the third week of one of the largest entertainment strikes in recent memory.

News Clip: "This is the first time in 15 years that TV writers are on strike."

News Clip: "They say that they're calling for fairer contracts after not being able to reach an agreement on negotiations last night."

News Clip: "The last time there was a writers' strike, Netflix streaming service was just 10 months old. Streaming has completely overhauled how Americans consume content, and subsequently, it has appended how shows are produced, but WGA members say their pay and power hasn't kept up with the times."

Brooke Gladstone: More than 11,000 people are participating in the action by the Writers Guild of America resulting in shows like The Tonight Show and Last Week Tonight going dark, and a lot of big names have shown up on the picket line, from Tina Fey to Seth Meyers, to Rob Lowe, to Jason Sudeikis, and some former cast members of The Office.

News Clip: "Everybody, three actors here who used to be on The Office. We can't talk because our words come from writers. We need the writers. We need a good deal for them. Support for them supports us all."

Brooke Gladstone: At the heart of the strike are concerns about the changes streamers like Netflix have presented for writers' pay and career development. For one, the streamers don't pay writers residuals. That's the cut of cash they traditionally get every time their show is rerun on TV. Now, writers are more likely to be paid for the number of days they work on any given show, but while streaming technology is new-ish, the fundamentals behind the strike, our tale as old as, well, the entertainment industry itself. Emily St. James covered TV at publications like Vox and the A.V. Club for about 15 years, including the 2007 writers' strike which lasted 100 days. Now, she's a TV writer herself.

Emily St. James: I feel very strange saying I am a TV writer when I worked one day in that job and immediately went on strike, but you know what? I'm happy to be in that space, and I'm also dedicated to this strike.

Brooke Gladstone: I spoke to Emily fresh from the picket line about some of the less-than-true notions about the current strike and the last one that she's seen in the coverage. For example, the notion that when writers stopped working in 2007, there was an explosion of reality TV shows.

Emily St. James: The idea that the last strike created reality television is a very strange myth that just refuses to go away and what really bugs me about it is all it takes to prove it's not true is googling when Survivor debuted. It debuted in 2000.

Jeff Probst: "In the end, only one will remain and will leave the island with one million dollars in cash as their reward. 39 days, 16 people, 1 survivor!"

Emily St. James: Survivor is generally noted as the dawn of reality competition TV. It's not the first example of it, but it's the first really huge hit that American TV had, and, of course, from there, we have all sorts of copycats, and we have shows like American Idol and shows like The Bachelor. They're all really hit big, and all of those shows debuted before 2005. The strike is in 2007. When you get to the top 30 TV shows of the 2007-2008 season, which is the one affected by the strike, yes, the top five shows are all reality. There are two installments of American Idol and the three installments of Dancing With the Stars each week. Those were the top five shows for the TV season before and the TV season after. If you look at the rest of that top 30 list, you see all kinds of scripted shows. You see Grey's Anatomy and Lost and Desperate Housewives and CSI and NCIS and et cetera. What happened was as the strike was heating up in 2007, it's roughly at the same time as networks would realize you can make a reality show very cheaply. For instance, a few weeks before the strike in 2007, they aired the first episode of Keeping Up With the Kardashians. Of course, Keeping Up With the Kardashians becomes this mega phenomenon that ultimately becomes one of the expensive reality shows because they have to keep paying the Kardashians to stay involved, but at the time, it's this cheaper little show that they can throw on the air and get a pretty good number from. I think a lot of people look at that correlation and they're like, well, that must be because of the strike but really it's not. These networks were not canceling scripted programming to make reality shows. They were just starting out making their first programming, and they were making reality shows. The two events just coincided.

Brooke Gladstone: Well, how about the collapse of civilization as we know it [laughs], by which I mean the lasting influence of the '08 strike on The Apprentice.

Donald Trump: "Hey, look, you claim to be like me? The difference is I work hard. You've been lazy. You've been nothing but trouble, and now you cut them off as they're fighting each other for who should be fired. Michael-"

Michael: "Yes, sir."

Donald Trump: "-you're fired."

Brooke Gladstone: The story goes that the Donald Trump vehicle, which debuted in 2004, was saved from cancellation by the 2007-2008 strike, thus allowing Trump to continue having a primetime platform that would lead him to the presidency.

Emily St. James: We can debate all day long the role of The Apprentice in Trump's ascent to the presidency. I think there are valid cases on both sides.

Brooke Gladstone: He was a New York schnorrer before he became an international sensation.

Emily St. James: I think that what is not accurate is that The Apprentice was saved from cancellation by the strike. What happened was in May 2007, it was not on NBC's fall schedule. Everyone was like, does that mean The Apprentice is canceled because its ratings had been slumping to that point? It had gotten fairly low in the ratings after being an enormous hit for its first two seasons. There was this consensus that maybe the show's canceled but at the time, the NBC brass were very clear that no, we're just trying to work out a new deal with Trump, and with Mark Burnett, who's the producer of that show. They eventually did within a few weeks, and they went into production on the first season of what became the Celebrity Apprentice that summer. Now Celebrity Apprentice was a natural way to try to boost the ratings of a franchise that had fallen, and for whatever reason, whether it's because it did debut in that strike period when there wasn't a lot else on, or because it had celebrities, its ratings did go up a little bit. It did not, however, become a massive hit in the same way it had its first couple of seasons and then it very quickly fell off. I do not think that Donald Trump is president because there was a writer's strike. I think that's way too many butterflies causing hurricanes, but it is true that the Celebrity Apprentice debuted in the middle of that strike period.

Brooke Gladstone: Why does the idea of a reality TV boom in the last strike persists, given if you look at the shows that were running before, during, and after, there weren't additional shows? Why does the idea continue?

Emily St. James: We have this sense that unscripted programming is somehow emblematic of the end of the world. We jokingly talked about the collapse of civilization a few minutes ago, but you really would look at writing about reality television in the 2000s, and people would write about it as though it was just this extreme pernicious evil. One of the things about unscripted programming, whether you're looking at the TV or film world, is it's always been there. We've always had unscripted shows from the earliest days of television. One of the first big hits was The $64,000 Question.

Brooke Gladstone: I was thinking more Candid Camera might be one.

Emily St. James: Sure, Candid Camera is one, Queen for a Day, This Is Your life. All of these shows that are playing off, they're very different from the reality shows we have today, but they are unscripted programming of the time. They were actually written about in similar ways. During the game show craze of the '50s, you can find all sorts of TV criticism that is like, these shows are just going to be the end of all of us, and they're not air tight enough or whatever. It's a way that people have always thought about this kind of programming.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's talk about the impact of the strike. I was thinking of the last strike, the 2007 strike, when the life of Jesse Pinkman was saved.

Emily St. James: One of the other things that I'm fascinated by is the number of narratives of what happened to scripted shows in the 2007-2008 strike are just incorrect. One that is actually correct that a lot of people don't know is that the beloved series Breaking Bad, Bryan Cranston as the chemistry teacher who becomes a drug kingpin, was cut short in its first season. It was originally supposed to have more episodes, then the strike happened. If you've always wondered why are there only seven episodes of Breaking Bad season 1, that's why. Now originally, season one was supposed to end with the death of Jesse Pinkman played by Aaron Paul. It was supposed to be like a moment that underlined the consequences of Walter White's choice to start cooking meth. The writers had come to really his performance and realized everything he was bringing to it. As they were on strike, Vince Gilligan, a few of them started thinking about, do we really need to kill this guy? Would it be more interesting if this character lives. If you've watched all five seasons of Breaking Bad, it is impossible to imagine that show without Jesse. He is that show soul in so many ways.

Jesse Pinkman: "I am not turning down the money! I am turning down you! Ever since I met you, everything I ever cared about is gone!"

Emily St. James: Yet, if the strike hadn't happened, he would have died. I mean, obviously, the actor would still be alive [laughs]. I think what is true of creative people is that they continue to be creative even when they are not working on new shows actively. Creative people are going to come out of this strike with ideas that will make some of your favorite shows even better. Just think of Jesse Pinkman, how many Jesse Pinkmans will be saved because of this show?

Brooke Gladstone: You've said that every time there's a strike, it's really about new technology. Every innovation seems to shortchange the writers. You found that this goes all the way back to the writers' strike of 1960. Could you walk me through that?

Emily St. James: The writers' strike of 1960 was predominantly designed to get screenwriters some sort of residuals for movies that were made before the dawn of television, so movies from before 1948. The Writers Guild eventually did win that after a long, bruising strike. That is just the basis of every strike thereafter. There's always some new technology that's coming in that is not strictly covered by the previous agreements made by these unions, and then studios are trying to find a way to find loopholes within that because of the new technology. Then a strike is usually about closing those loopholes up.

Brooke Gladstone: So in the 1980s, it was about VHS, right?

Emily St. James: It was about VHS. There was also the elements of what happens when something is aired on cable. In the 2000s, there's so much of it about DVD and DVR. It is always some new technology that's coming in. We're talking about the writers because the WGA is historically more likely to strike than any of the other big unions, but every single person in Hollywood is affected when these new technologies come in.

Brooke Gladstone: The first time I really thought about this was in the very early '90s. Peggy Lee wrote six songs and provided the voices for four characters in Lady and the Tramp, which was made in 1955.

[MUSIC-Peggy Lee: He's a Tramp]

He's a tramp, he's a scoundrel

He's a rounder, he's a cad

He's a tramp, but I love him

For which he was paid $3,500. She sued Disney for failing to pay her when Lady and the Tramp was released on videotape, right?

Emily St. James: Yes.

Brooke Gladstone: She won.

Emily St. James: When you have created a creative work that lasts forever and ever, like Lady and the Tramp, true cinematic classic, I think you are owed some money from the continued success of that property. Would anybody be watching Lady and the Tramp without Peggy Lee's involvement? I don't think so. She made that a much better movie than it could have been otherwise. That is the thing that is often hard to understand in a culture that I think is often more disposable, things that we have are increasingly built to last a couple of years and then be thrown away.

Brooke Gladstone: The technology people are worried about is technology that's been around for about 20 years, that streaming. It's also about AI, right?

Emily St. James: Yes, as my friend Alissa Wilkinson, my former colleague at Vox has pointed out, the fear is less that an AI can be better than a writer because everybody acknowledges that's not true. The fear is that an AI could write something just good enough that enough audiences would fall for it. Again, I have a lot of faith in TV audiences. I don't think that would happen. I certainly think there's a world where a decade from now, maybe there's a lot of stuff that is cheaply generated by AI, and that's one of the reasons the Writers Guild is striking around this issue.

Brooke Gladstone: The point is that if AI gets used, no matter how it gets used, the union is asking for some boundaries.

Emily St. James: Yes. Basically, the idea is that if you are going to use AI as a tool, it is there to supplement or bolster. It is not there to create. If you are working on a project about some true story, then your studio might come to you with like, here's a new piece of research that we found. Here's a new magazine article. Here's a new Wikipedia article, something like that. They're well within their rights to hand you that if you're working on a story. I think that if you're already in production, if you're already working on the thing, and the studio has a thing that wants to hand you, like there is a world in which AI becomes a tool that can be helpful, it's the question of making it the tool rather than the thing that is generating from the first.

Brooke Gladstone: You say that people have expected this strike for about three years. Really back to the 2020 contract negotiations, which I guess got settled fast because of the pandemic. I guess you could assume given that the strike was anticipated, that the networks and streaming services were prepared, the writers were prepared. Is this another 150-day strike?

Emily St. James: I think that probably someone like Netflix has stuff banked up. Eventually, there's going to come a point where they're going to be looking at all the stuff they have banked and realize, oh, this is not going to continue past this point because production has shut down. Now Netflix is again has a lot of international production and international production is not affected by this at all. The next season of Squid Game precedes a pace presumably. They do have that aspect that is a wrinkle this time around that wasn't there in 2007. You're already seeing programming gets shut down, late night shows are not airing. You're going to see probably in the fall, some of the big network shows are going to be delayed. You're going to see a delay in some of the big ongoing streaming shows. When Stranger Things finally comes back, those kids are all going to be like on pension plans. There is this looming deadline, which is June 30th, is the expiration of the contracts that AMPTP, the group that represents all the studios has with the DGA, the Directors Guild, and SAG, the Screen Actors Guild. There is an equal amount of irritation and frustration and anger among members of those guilds. Now, will that result in a strike? That is hard to say. As I noted, the Writers Guild has historically been the union that is most likely to go on strike, but if SAG or DGA, or both of them, join in on the strike, then things I think get very complicated and very interesting. I would be very intrigued to see what happens if all three of the major creative unions go on strike.

Brooke Gladstone: Don't you think that the coverage of strikes has been a lot more positive in recent years than in years past?

Emily St. James: You look at polling for how positively Americans feel about labor unions, and it's at its highest rate since 1965.

Brooke Gladstone: I think this is another post-pandemic effect.

Emily St. James: I think that there is a real desire to have change. One other big difference is the journalists who are covering this are often unionized under the WGA themselves, the WGA East rather than the WGA West, but they are a sister organization. I feel that there is a lot more positive coverage right now because there is an acknowledgment of the idea that if change is going to happen, it's going to happen because people push for it and take action for it. I think there's more of an understanding of that now than there was in 2007, or than there was, you know, in some other strike, even five years ago.

Brooke Gladstone: I know some people are irritated a little bit in the working man's hero narrative that the WGA sometimes strikes, but the fact is that since the pandemic and the attention of the American public, however, briefly on the role of essential workers in our lives, has had an impact on the perception of work in general and on inequality.

Emily St. James: I think there has never been a period in American history when people have been more aware of the idea that a small number of people have a disproportionate amount of the wealth. Everyone can see the way that that affects whatever industry they're in, regardless of that industry. The work that I do is not a blue-collar job. It is very, very white collar, but it's a similar situation, where I am getting paid what is ultimately a pittance compared to what is being made by the people who are my vast, enormous corporate overlords. That was true when I was at Vox. That was true when I was at the A.V. Club before that. I think it is a situation that has united a lot of people who traditionally maybe would not have been united. It's been fascinating to watch that solidarity develop among the various groups who do very different things here.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much.

Emily St. James: You're welcome.

Brooke Gladstone: Emily St. James is a former TV critic turned TV writer.

Emily St. James: For one day.

Brooke Gladstone: For a day. Her latest article for Vanity Fair was called "Can We Really Blame Trump (and the Reality Boom) on the 2007 Writers Strike?"

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.