Why is Trump’s Campaign Suing a Small TV Station in Wisconsin?

( Priorities USA/YouTube )

Bob: Hi, this is Bob Garfield. On last week's pod extra, we took a close look at the Lincoln Project, the political action committee known for funding excoriating anti-Trump advertisements. Check out that episode if you haven't already. With fewer than 100 days before the election, our social media feeds and TV airwaves are already chock-full of political ads from Republicans and Democrats for and against candidates all the way up and down the ballot, which is why we are running this episode from the podcast Trump Inc.

They make the show right down the hall from us at WNYC, or anyway, they did, now like OTM, they're producing their show out of bedrooms all across the tri-state area.

Anyway, this is the story of one TV ad that really got under the president's skin. Here's Trump Inc. co-host, Andrea Bernstein.

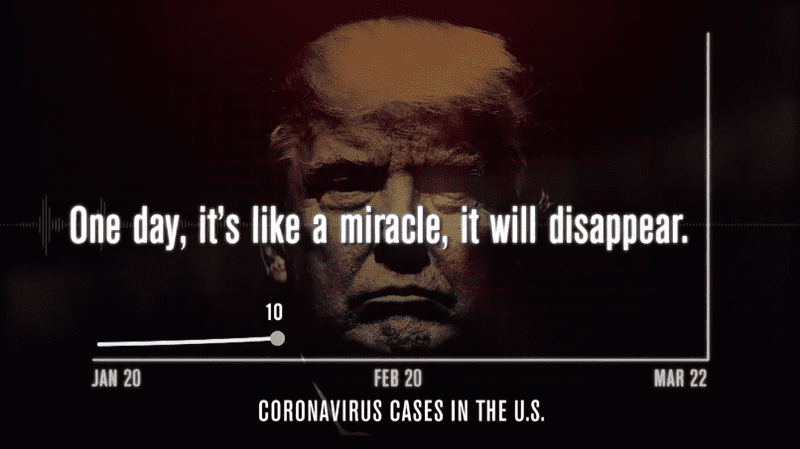

Andrea: In March, a super PAC placed an anti-Trump advertisement on local television stations in battleground states.

Trump: The Coronavirus, this is the new hoax. We have it totally under control.

Andrea: There's a visual on the screen, a line counting COVID-19 infections ticks up and up.

Trump: I think we've done a great job in keeping it down to a minimum.

Andrea: Clips of the president dismissing the virus play in the background.

Trump: Priorities USA Action is responsible for the content of this ad.

Andrea: Priorities USA is a type of super PAC, it supports Joe Biden. It can collect unlimited contributions from almost any source for expenditures independent of the Biden campaign. The day after the advertisement first aired, the Trump campaign sent cease and desist letters to TV stations. The campaign said it sent these letters to stations that aired the ad in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

In the letter, the campaign claimed that the ad was deliberately false and misleading because it featured clips taken from different contexts placed together in a way the campaign considered deceptive. "Should you fail to immediately cease broadcasting P-USA's ad," the letter reads, "Donald J. Trump for president Inc. will have no choice but to pursue all legal remedies available." A spokesperson for Priorities USA told us that none of the 72 stations that ran the ad pulled it from the air.

Then, a few weeks later, the Trump campaign did something that as far as we can tell, no other presidential campaign has ever done, it filed a defamation suit over the ad. The campaign didn't sue the super PAC, it sued just one of the local stations, WJFW, a small NBC affiliate in northern Wisconsin.

Justin: Welcome to Newswatch 12 at 5:00. I'm Justin Betty. Today, President Trump's campaign team has sued WJFW, our TV station over a political ad which you may have seen. That ad might have--

Andrea: The Wisconsin lawsuit is part of record-breaking legal spending by a presidential campaign. Disclosures show the campaign has raised over $342 million and spent 16.8 million on legal services alone, and this is just the campaign, not associated committees. The legal spending is more than any past presidential campaign and more than 10 times what Joe Biden's campaign has spent on legal services. In February of 2020, President Trump's re-election campaign began filing a series of defamation suits against news outlets.

Justin: Your campaign today sued the New York Times for an opinion case. Is it your opinion or is it your contention that if people have an opinion contrary to yours that they should be sued?

Trump: Well, when they get the opinion totally wrong as The New York Times, and frankly, they've got a lot wrong over the last number of years, so, we'll see how that-- Let that work its way through the courts.

Andrea: The first three lawsuits were filed in rapid succession against The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN. The suits claimed that opinion pieces linking the Trump campaign to Russia were false and defamatory. In its filings against the New York Times and The Washington Post, the campaign alleges, "A systematic pattern of bias against the campaign." The lawsuit claims the publications are extremely biased against Republicans in general. The campaign also sued CNN over an opinion piece that it published after President Trump gave an interview to ABC News's George Stephanopoulos.

George: If Russia, if China, if someone else offers you information on opponents, should they accept it or should they call the FBI?

Trump: I think maybe you do both. I think you might want to listen, there's nothing wrong with listening. If somebody called from a country, Norway, "We have information on your opponent," Oh, I think I'd want to hear it.

George: You want that kind of interference in our elections.

Trump: It's not an interference, they have information, I think I'd take it.

Andrea: The opinion piece that came after, it was written by Larry Noble, a CNN contributor and former general counsel to the Federal Election Commission. In it, he commented, "The Trump campaign assessed the potential risks and benefits of again seeking Russia's help in 2020 and has decided to leave that option on the table." Lawyers for the Trump campaign argue Noble's article was defamatory.

In a filing, they say, Trump's interview with Stephanopoulos isn't relevant, and that President Trump was talking about Norway, not Russia. They call his comments about being willing to accept foreign assistance relatively innocuous. Lawyers for The Times, The Washington Post, and CNN are asking courts to dismiss the complaints. First amendment lawyers we spoke with said it's very difficult to win a defamation suit if you're a public figure like the president.

After the initial three suits against The Times, The Post, and CNN, the campaign filed its fourth defamation lawsuit, the one against that TV station in Wisconsin. On April 13th, President Trump's re-election campaign sued Northland Television LLC which owns WJFW. Trump Inc. reporters, Katherine Sullivan, and Meg Cramer wanted to understand all of the campaign's spending on legal services and how it fits into the nexus of the Trump campaign, the White House, and the business of Trump.

Meg and Katherine examined spending by the Trump campaign and four affiliated committees, talked to lawyers and campaign finance experts, and read through hundreds of pages of lawsuits. Their story starts with a seemingly straightforward question, why did the Trump campaign file a lawsuit against a small TV station in northern Wisconsin? Meg Cramer takes it from here.

Meg: We asked the campaign and their lawyers and they didn't get back to us, and when I reached out to WJFW, a lawyer for the station told me they weren't talking to the press about the lawsuits or anything else, so, I called a reporter who lives in the area.

Ben: I am recording audio on my end as well.

Meg: Amazing. A radio reporter.

Ben: Sure, I can introduce myself. My name is Ben Meyer and I am a special topics correspondent at WXPR Public Radio here in Rhinelander, Wisconsin.

Meg: Rhinelander is a city in Oneida county in way northern Wisconsin, population, about 8,000. Ben grew up in southern Wisconsin where the landscape is rolling hills and open farmland. Northern Wisconsin is a bit more wild. He told me when his mom visits, she feels claustrophobic, like, she can't get out of the trees. Ben has been a local journalist in the area for about a decade. He covers water resources, things like water quality and mining pollution.

Ben: The counties where I do most of my work have some of the highest concentration of freshwater lakes in the world. Oneida County alone has more than 1,000 lakes.

Meg: Before making the jump to radio, Ben worked at different local news outlet in Rhinelander, the TV station WJFW.

Ben: I started as a reporter and producer. I wore a lot of hats along the way. I was an executive producer at one point. I think they gave me the title of managing editor at one point. I was the news director for a couple of weeks. I loved working there. I loved my coworkers and I loved doing stories about and with and for my neighbors.

Meg: Ben knows a ton about the history of the station. He used to give tours.

Ben: The first thing I would point out is, WJFW is really unorthodox history.

Meg: It was founded by a local congressman while he was still in office.

Ben: He founded it in 1966, a little building under a big tower.

Meg: Two years later, a small plane flew into the tower knocking it down onto the building, the three passengers on board died in the accident. Next stop, master control.

Ben: We say, "Okay, someone sits here 24 hours a day to make sure the commercials are on at the right time and make sure that if--"

Meg: Passed the newsroom and into the studio.

Ben: The set is awesome, the set looks great.

Meg: Picture a lot of warm wood paneling.

Ben: You pan away from the set, there's an old couch over there and a couple of old chairs over there, an exposed the rafter up here or whatever, but it's fine, it looks great on TV, that's all that matters.

Meg: Then what's the next stop on the door?

Ben: The next stop is that's it because it's not a big station. It's a small market TV station.

Meg: You worked there for eight years, is that right?

Ben: Between seven and eight, seven and a half, I think.

Meg: When the Trump campaign sued the station, Ben noticed.

Ben: The first thing that went through my head is, "Wow, people are going to start hearing the name Rhinelander because of this Trump campaign action. A lot of people that have probably never heard the name Rhinelander Wisconsin before." That's the first thing that went through my head.

Justin: Our station neither endorses nor opposes this ad, nor any other--

Meg: The day the lawsuit was filed, WJFW lead with the story in their five o'clock newscast.

Justin: That ad continues to be aired on many TV stations across the country. However, WJFW is the only station named in this suit and that suit still has not yet been served. We have only heard about it and read about it through other news organizations and on the President's campaign website. In some other news, many people are looking forward to the day when they can just go outside and go to their favorite events again, but organizers for several local events say their events.

Meg: Before we go any further I think it's important to mention that none of the legal experts I talked to for this story, thought that the campaign's lawsuit against WJFW had any merit. Matt Sanderson, who served as counsel for senators John McCain and Mitt Romney told me he thinks the Trump campaign is engaging in scare tactics. He said, as a longtime Republican and someone who's worked in the trenches for many, many Republican candidates, I'm appalled to see a Republican president suppressing speech.

Another experienced Republican election lawyer who didn't want to be named because they still work in the space said they thought "most election lawyers would not be able to file this without their skin crawling." We asked Husch Blackwell the firm representing the Trump campaign if they felt the lawsuit against WJFW would be successful. We did not hear back. By filing its lawsuit in Wisconsin, the Trump campaign picks up a possible advantage. Some states have what are known as anti-SLAPP laws. SLAPP S-L-A-P-P, stands for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, and anti-SLAPP laws make it harder and more expensive to file frivolous defamation lawsuits.

For example, if a court decides that a defamation suit has no merit, anti-SLAPP laws might require the person who filed the suit to cover the defendant's legal expenses. Florida, one of the states where the ad aired, has an anti-SLAPP law on the books. Wisconsin does not. WJFW was not the only station in Wisconsin that ran the Priorities USA ad but then noticed that it was the only station in Wisconsin that got sued.

Ben: Then what went through my head is, "Okay, why? Why not a station in La Crosse, Wisconsin or Eau Claire, Wisconsin, or anywhere else in Wisconsin or any other small market station that has aired this ad in the United States?"

Meg: Ben didn't know. He still doesn't but he had some educated guesses.

Ben: My speculation was that, "Okay, WJFW might be a little different than those other small-market stations because WJFW has a really small ownership group."

Meg: That group, Rockfleet Broadcasting, owns just three stations, this NBC affiliate in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, and two stations that share a studio in Bangor, Maine.

Ben: It's possible in my mind, and again, speculation that the Trump campaign saw a station with a small ownership group as an easy target, a group that they could bully around a little bit more than a station that fell under the umbrella of a big ownership group.

Meg: Ben noticed something else about the lawsuit. Initially, the campaign filed it in Price County, WJFW is headquartered in Oneida County.

Ben: Price county is immediately to our west. It's smaller. Its population is fewer than 20,000. This entire area, the entire North Woods in the 2016 election was red. All counties voted for Trump. They voted for Trump to different degrees as you can imagine, though. Trump won Price County by about 25 points.

Meg: A higher margin than in Oneida County.

Ben: When I was asking the question that you're asking in your head right now, well, if the station's in Oneida County, why would they file it in Price County? Maybe the campaign figured, "All right. We'll file in Price County, which is still in WJFW's viewing area, and perhaps we'll get a little bit more sympathetic public. We might get a little more sympathetic judge, and that could help our case."

Andrea: We know that Trump has done things like that before. To help us understand what's going on in Wisconsin in 2020 we looked back at a case filed in 2006 in New Jersey against a journalist who wrote a book about Trump. Susan Seager is a media defense lawyer who teaches at the University of California Irvine School of Law.

Susan: I first became interested in Trump when he filed a lawsuit against Tim O'Brien when Tim O'Brien said he wasn't a billionaire.

Andrea: O'Brien was writing about business for the New York Times in those days, and he'd written a book about Trump that showed he was 100 millionaire, not a billionaire. Trump's sued for defamation seeking $5 billion in damages.

Susan: I didn't really know Trump that much. I just know he was a celebrity. I followed that case, and I knew he would lose and he did lose.

Andrea: It was a high profile case that displayed a lot of the characteristics of Trump's litigation strategy, including that Trump didn't file it in Manhattan, which is where the publisher and the Trump Organization are headquartered but in South Jersey, where one Trump political ally had a hand in appointing judges. In the lawsuit, there were thousands of pages of motions filed. Depositions were taken. They were high priced lawyers on both sides. If you're a First Amendment specialist, it's a hard case to forget.

Susan: Then it was just bubbling around the back of my mind. Then when he was running for president, and there were stories about all the lawsuits that he was a part of both as a defendant and a plaintiff I started researching other lawsuits of involving Trump and I was shocked to see so many.

Andrea: USA Today reported in 2016, that Trump had been involved in at least 3,500 lawsuits.

Meg: Seager started keeping track of the cases where Trump sued for defamation or tried to bring his critics to court. She keeps a set of manila folders with the cases from before Trump became president. This year, she started a new set of folders and added the four defamation suits filed by the campaign. I asked Susan Seager the same thing I asked Ben. Why out of all the stations that aid the ad, did the campaign end up suing WJFW?

Susan: I do think that maybe they thought they'd go after someone small but what his real goal is, is to stop all TV stations from running these ads.

Meg: It's not just that the Trump campaign sued a small station that's less likely to have the legal resources to fight a defamation suit. It's that they sent a signal to other stations like WJFW. We are willing to sue. We don't know whether or not this lawsuit will discourage other stations from running political ads that are critical of the president. A spokesperson for Priorities USA told us they haven't had any trouble placing ads since the campaign sued WFJW. Seager estimates that fighting a defamation lawsuit brought by a high profile group like a presidential campaign could cost anywhere between $100,000 and $250,000, just to go through the process of getting dismissed.

Susan: If you can't get it dismissed at the very beginning, then there's depositions. There's exchange of documents and that could be $500,000, or even $1 million.

Meg: Publishers often have liability insurance.

Susan: Sometimes they have a big deductible, though. Sometimes the policy limit may not be the same as what your legal fees are.

Andrea: In this case, WJFW owners did decide to fight the lawsuit, and they brought in an experienced legal team. We asked WJFW's owners how much they expect it's going to cost to defend the case and whether or not the station has insurance. They declined to say citing confidentiality. The station commented, through a lawyer, that WJFW has no choice but to fight the Trump campaigns attempt to bully a small-market broadcaster into surrendering its first amendment rights.

The public counts on local broadcasters especially in an election year to remain free to air criticisms of public officials. After the case was initially filed, lawyers for the station filed papers to move the case to federal court, and it was moved to federal court. The station's lawyers also asked the court to dismiss the complaint. That's still pending. Priorities USA the super PAC that paid for the ad joined the case as a defendant. Their lawyers have also asked the court to dismiss.

We asked the Trump campaign and its lawyers why they chose to sue WJFW why they filed their case in Price County and if their lawsuit was intended to deter stations from accepting advertising like this in the future. They did not respond. Before we go on, I want to talk about something we've explored before on Trump Inc., how Trump's fundraising success is due in part to his openness to taking requests from people who gave him money. We did a whole episode on this earlier this year. Here's an excerpt of that from my co-host, William Morris.

William: April 30th, 2018. It's a small gathering in a private dining room in the Trump International Hotel in Washington. It's a collection of mostly wealthy, well-connected people. They've pledged financial support for a group that's promoting Trump's reelection.

Speaker 1: Hi, everybody. Once again, [unintelligible 00:19:49] Thank you for being here.

[applause]

William: People take their seats, drinks are poured, dinner is served. The phone that's recording all of this must be pretty close to the president. Trump talks about what he wants to talk about golf-

Trump: How good a golfer is he? Much better than me.

William: -politics-

Trump: The congressional, whatever it is.

William: -the intersection of golf and politics.

Trump: You know that Kim Jong-un is a great golfer, you know that, right? Better than me. [crosstalk].

William: A lot of the guests here want things from the president.

Andrea: Throughout his presidency, Trump has made it clear he will favor people who give him money or patronize his businesses. The man who released this tape, Lev Parnas was working on an energy deal in Ukraine. He was invited to this dinner after promising a six-figure donation. Here we are, Trump and his affiliated committees have raised lots of money, record-breaking amounts, and they're using some of that money to fund a series of defamation lawsuits.

Katherine: I'm here, can you hear me?

Andrea: Hello? We go back now to Meg Cramer and Katherine Sullivan.

Katherine: Hello from my childhood bedroom closet in downtown New York.

[laughter]

Meg: Katherine and I have been trying to figure out just how much money the Trump campaign and affiliated groups are spending on legal services.

Katherine: We looked at all the receipts for expenditures that were classified as legal consulting or legal and IT consulting or legal and compliance.

Meg: We took the legal expenses and added them up for the RNC, the Trump campaign, and three other related committees. Those committees are America First Action, which is a super PAC that supports Trump and can raise unlimited amounts of money from donors, and two committees that raise money jointly for Trump and other Republicans.

Katherine: That's Trump victory, Trump Make America Great Again Committee, and America First Action. Altogether, we found that all of these entities have spent over $37 million on legal matters.

Meg: Comparable Democratic groups have spent less than half of that in the same period since 2017. More than $37million across all these affiliated committees, where's that money going? One thing we know is that the campaign covered some of the legal expenses related to the Muller probe.Also, the campaign has been named as a defendant in at least a dozen lawsuits by plaintiffs ranging from employees who say they were discriminated against, to protesters who say they were attacked at Trump rallies. The campaign has denied these allegations.

Trump: I knew this would happen. I knew it was going to happen but--

Meg: Trump actually complained about this at one of his coronavirus briefings in March.

Trump: When I ran, I said it's going to cost me a fortune not only in terms of actual cost. Look at my legal costs, you people, everybody is suing me. I'm being sued by people that I never even heard of. I'm being sued all over the place. I'm doing very well but it's unfair.

Meg: To figure out what other kinds of legal work Trump's campaign is paying for, Katherine put together a list of around 100 different entities doing legal consulting for the campaign and affiliated groups.

Katherine: Some were really big corporate law firms. Jones Day, for example, was the highest-paid firm and they've made $13.3 million from the campaign and these committees.

Meg: Jones Day is where Trump's former White House counsel, Don McGann works.

Katherine: Then there are some smaller entities, for example, there's one owned by the former White House ethics counsel, Stefan Passantino, the campaign and the RNC have paid his company more than $400,000.

Meg: You can't exactly tell what kind of legal consulting these groups are doing.

Katherine: I also looked up all the lawsuits that I could find in which the Trump campaign was a party but it's not a perfect match to try and line up the cases with the payments to the law firms. A lot of the work that these firms are doing doesn't necessarily result in public-facing legal action. They could be doing research or consulting or giving advice or hiring opposition researchers.

Meg: On one side, you have this list of all these companies who've been paid for legal work by the campaign, and on the other, you have this list of cases and legal action, it's a shorter list that the campaign is involved in and you can't necessarily match them up.

Katherine: Right.

Meg: Taking a look at all these numbers, was there anything that caught your attention?

Katherine: I think the most surprising thing was that the second-highest-paid entity on this list was a firm called Harder LLP.

Charles: Hulk Hogan filed two lawsuits today in Tampa, Florida.

Katherine: This is Charles Harder, he's an attorney who specializes in high profile reputation defense lawsuits. He's the lawyer who represented wrestler Hulk Hogan against Gawker Media.

Charles: He alleges the defendant posted excerpts of the videotape at their website gawker.com--

Katherine: In a case that was being secretly bankrolled by Peter Thiel, a tech billionaire who went on to become a big supporter of and donor to President Trump.

Charles: Hulk Hogan will take all reasonable steps necessary to ensure that all persons and entities who were involved in this are punished to the fullest extent of the law.

Katherine: Hogan, backed by Thiel, won the case. As a result of the lawsuit, Gawker went bankrupt. We know that Harder started doing work for the Trump family in 2016 on lawsuits that Melania Trump filed against the British publication, The Daily Mail. The Daily Mail ended up retracting their story, apologizing, and settling for a reported $2.9 million according to the Associated Press.

Meg: We also know that Harder did defense work for Trump. When Stormy Daniels claimed Trump defamed her, she lost.

Katherine: It appears that a lot of Harder's work involves responding to unfavorable media stories about the president. He's threatened or taken legal action against Author, Michael Wolff, Mary Trump, Steve Bannon, and Omarosa Manigault Newman, plus news outlets like The New York Times and CNN. ABC reported that Harder recently sent a letter to Michael Cohen demanding that he halt writing a tell-all book about his work for Trump.

Meg: In late July, Cohen filed a lawsuit against Attorney General, Bill Barr, and the Bureau of Prisons claiming he was sent back to prison, "In retaliation for doing a book about the president." The Justice Department has declined to comment. The first Trump campaign payment to Harder's firm comes in January 2018. Since then, the campaign has paid his firm over $3 million just for some context. That's more than the Biden campaign has spent on legal services total. What do we know about the work that he's doing just for the campaign?

Katherine: Again campaign finance laws don't require campaigns to disclose much detail about their spending. We know from legal filings that he defended the campaign in a wage discrimination claim brought by a former campaign staffer who says Trump forcibly kissed her. The White House denied this, the staffer Alva Johnson dropped her lawsuit after several months.

She told The Daily Beast at the time, "I'm fighting against a person with unlimited resources," she added, "That's a huge mountain to climb." Then, it's Harder that's representing the Trump campaign in three of the defamation lawsuits. The ones against The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN, but the Wisconsin case is being handled by a different law firm, Husch Blackwell. They've been paid around $200,000 by the campaign.

Andrea: Trump Inc. reporters, Katherine Sullivan, and Meg Cramer. For a campaign that's raised over $300 million, the money it cost to bring these cases is basically nothing. It's a situation where no lawsuit is too big or too small. After losing his lawsuit against the journalist, Tim O'Brien, Donald Trump told The Washington Post that he knew he couldn't win but he sued anyway.

He said, "I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees," and they spent a whole lot more. "I did it to make his life miserable, which I'm happy about." Trump doesn't have to stake any of his own money on the lawsuits against The Times, The Post, CNN, and WJFW. His generous donors are picking up the tab.

This episode was reported and produced by Meg Cramer and Catherine Sullivan. Our editor is Erica Metzger. Jared Paul does our sound design and original scoring. Hannis Brown wrote our theme and additional music. Special thanks this week to Karl Evers-Hillstrom, Brandon Fisher, Eugene Volokh, Polly irungu, and Sahar Baharloo. Matt Collette is the executive producer of Trump Inc. Emily Botein is the vice president of original programming for WNYC, and Stephen Engelberg is the editor in chief of ProPublica. I'm Andrea Bernstein. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.