Unlearning White Jesus

( Bob Schutz / Associated Press )

Katya Rogers: I was in a meeting the other day with Liz and Dan, they're part of the team that organizes our pledge drives at WNYC. Oh, this is OTM producer, Katya Rogers. Anywho, I was in a meeting with them discussing the end of year fundraising message, and they told me that only 1.2% of On the Media listeners donate to the show. I said, "Bloody hell, that's rubbish." Yes, the shock of that low, low number brought the English right out of me.

Here I am to ask the other 98.8% of you guys, the ones who have never donated before, to please, if you can afford it, put a few pennies in the hat for us before the year is out. We promise to keep bringing you enriching, worthwhile journalism twice a week, but we're going to need your help to do. Go to onthemedia.org and hit the donate button or text OTM to 70101. Thanks for all your help. We really appreciate it.

Speaker 1: With the travel restrictions and lockdown measures, this holiday season simply isn't as merry as years gone by, but it still twinkles with remembrances of times passed. The snow, the lights, and of course, the public nativity scenes depicting the birth of Jesus, presenting the family with very rare exceptions as white. The same can be said of his ubiquitous adult portrait with skin and hair of radiant gold and soft baby blues fixed on the middle distance. Eloise Blondiau, our resident graduate of Harvard Divinity School, traces how the historically dubious image became American canon and its consequences.

Eloise Blondiau: The first picture of Jesus that Detroit passed and Mbiyu Chui remembers seeing, belonged to his grandmother, it hung in her bedroom.

Mbiyu Chui: Of course, it was an image of a blonde hair, blue-eyed guy. That picture bothered me, but I never would say anything. I dare not tell my grandmother, "Would you please take that picture off the wall?" [laughs] The eyes moved like it was following you around the room, and at night, in the dark, it glowed. In the '60s and '70s, we had a lot of stuff that glowed in the dark. [chuckles]

Eloise Blondiau: When you say the eyes were moving, the eyes weren't actually moving, you just felt like they were, right?

Mbiyu Chui: [laughs] No. They weren't actually moving, but as a child, you have an imagination.

Eloise Blondiau: You saw that image of Jesus, pale skin, long beachy waves, everywhere growing up in Detroit.

Mbiyu Chui: I couldn't explain why, but I just didn't feel comfortable with that picture. Of course, you see the same images when Jesus is portrayed anywhere in popular culture.

Eloise Blondiau: He was 12 years old in 1967 when his city turned into a war zone.

[music]

Speaker 2: Snipers ruled the city, gunfire flickered from neighborhood to neighborhood. All blocks smoldered, the smell was everywhere.

Eloise Blondiau: For five days, the so-called Detroit riots were credited with sparking the Black Power movement. Over 40 people died. In the aftermath, Chui drove down Linwood Street with his parents like he did every weekend. As usual, they passed the statue of Jesus that loomed over the intersection, seven-foot-tall, arms outstretched, long hair, white stone, but on this day, Jesus looked different.

Mbiyu Chui: They painted the statue black. Of course, the news spread all over the city. Everybody was, whoa.

Eloise Blondiau: Decades later, a house painter named Joe Nelson, would claim credit. He said he didn't want to pray to a white man. Before he covered Jesus's toes with black enamel paint, he wondered if some people would still stop and kneel at his feet, and apparently not. Soon, some white counter-protesters got involved.

Mbiyu Chui: Then in about a week later, they had painted it white again. Then, a couple of days later, it was black again. This happened at least three times. After the third time, they said, "Okay, forget it. We're not going to keep going back and forth," and they just left it black and it's still black to this day. [chuckles]

Eloise Blondiau: Sacred Heart, the Catholic seminary that owns the statue, said it intended to keep the statue black to commemorate the '67 riots. Sure enough, they repaint Jesus's black skin every few years. Mbiyu Chui, who ministers at a church a mile down the road, still sees it every weekend. In '60s Detroit, the Black Jesus signified a victory and a thriving theological debate, but the question is far from settled. Whenever this country reckons with its ongoing legacy of white supremacy, Jesus comes up, this summer included.

Speaker 3: An activist called Shaun King, issued the following demand on Twitter, quote, "All murals and stained glass windows of white Jesus and his European mother and their white friends should also come down. They are a gross form of white supremacy created as tools of oppression." Don't be surprised when they come for your church. Why wouldn't they? No one is stopping them.

Mbiyu Chui: There is no widespread reports of activist tearing down statues of Jesus.

Eloise Blondiau: President Trump says unnamed forces want to tear down statues of Jesus.

President Trump: Now they're looking at Jesus Christ.

Eloise Blondiau: The white Jesus image isn't going anywhere but where and how did it become the reigning image? Suddenly, actors cast as Jesus, have almost always been fair-skinned guys with blue eyes. In a long list of cinematic Jesus's, we have, for instance, Willem Dafoe.

Willem Dafoe: Father, I'm sorry for being a son.

Eloise Blondiau: And Christian Bale.

Christian Bale: Who are my kinsmen, but those who hear the Word of God and accept it.

Eloise Blondiau: In a striking break from precedent, white, blue-eyed actor, Jim Caviezel, who played Jesus in Mel Gibson's Passion of the Christ, had brown eyes on screen, and in an apparent nod to history, he also spoke Aramaic.

Jim Caviezel: [Aramaic language]

Eloise Blondiau: When people of color have played Jesus, it's more often in more lighthearted portrayals like John Legend in Jesus Christ Superstar or on Family Guy.

Speaker 4: I rolled into town on a [beep] yo mama's [beep]

Eloise Blondiau: Or the TV sitcom, Black Jesus.

Speaker 5: Oh, Negro, of little faith.

Speaker 6: All right, Jesus, what you got for me today? I've been good.

Speaker 5: Whatever you want, man.

Speaker 6: I need the numbers to the lotto.

Speaker 5: The lotto?

Eloise Blondiau: When Black actors played Jesus, it's not seen as realistic.

Megyn Kelly: Just because it makes you feel uncomfortable, doesn't mean it has to change. Jesus was a white man too.

Eloise Blondiau: That's Megyn Kelly on Fox News back in 2013, and she's wrong. Most historians, Christian or not, agree that a guy called Jesus existed 2000 years ago and had a following. There's some contention over whether he rose from the dead and was the son of God, but scholarly consensus is that he would not have resembled the fair-head surfer we all know. He probably had darker skin, hair, and eyes. In fact, every few years, a new allegedly more scientific rendering of Jesus makes the rounds.

Speaker 7: What then does science say is the true face of the son of God.

Speaker 8: British scientists drew this portrait of what they believed Jesus really looked like.

Eloise Blondiau: Whatever the tech, none of these educated guesses suggest the real man looks like an Arian hippie. Why does America cleave to that image?

Speaker 9: The most familiar Jesus appeared during the Renaissance, when artists started to show Jesus's human side, like Rembrandt, and that's how we see him today.

Eloise Blondiau: But that overlooked an abundance of Jesus depictions from the early church onwards, as dark-skinned or racially ambiguous. It also disregards the Great Rupture between Europe and the not-yet United States, driven by the Protestant Reformation.

?Speaker 10: Many Protestants hated the visual arts around them and destroyed images of Jesus because they saw these images as violations of the 10 Commandments.

Eloise Blondiau: Edward Blum, author of The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, says that for many years, residents of the colonies and later the US, had no images of Jesus.

?Speaker 10: When they would have dreams where they would see Jesus, they would see him behind a spider web or some veil. Then when Americans create imagery of Jesus in the 19th century, they do borrow somewhat from European artwork, but they also borrow from other myths and fabrications about what Jesus would look like.

Eloise Blondiau: Assuming the American white Jesus is entirely homegrown, from whence did it spring?

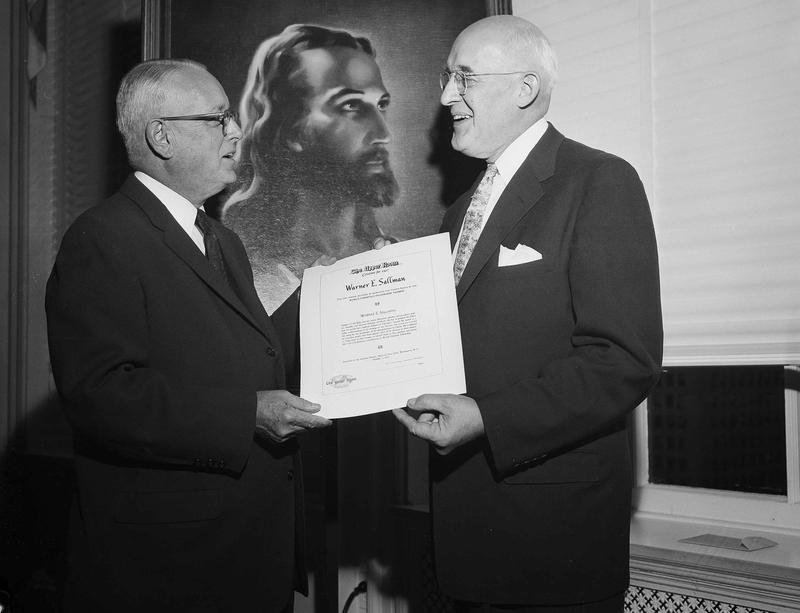

?Speaker 10: The Warner Sallman Head of Christ has become the lightning rod for the white Jesus, because it's so ubiquitous, because it became so abundant.

Eloise Blondiau: In 1940, Warner Sallman made the picture I guarantee you've seen. It has been reproduced by some counts over 500 million times. Sallman himself became somewhat of a celebrity as a result. He even went on TV to repaint the image, accompanied by a full choir.

Warner Sallman: I would like to begin the portrait.

Eloise Blondiau: The portrait is called the Head of Christ. His blue eyes are cast upwards, his hair gleams gold. A heavenly diffusion of light frames his head. Sallman was inspired in part, yes, by the romantic portrayals of Renaissance painters, but perhaps more so by the Hollywood headshot. Look at studio portraits of actors like Errol Flynn, and you'll see that gozzy light, that gazed into the middle distance. Sallman made Jesus a movie star.

?Speaker 10: It became so recognizable, and then any image created after it had to deal with it or look similar to it. There being one ridiculously recognizable Jesus, that is new.

Eloise Blondiau: There's a misconception that people only embrace pictures of God or God's wrought in their own image. That's not true. Sallman's image was and is beloved by all Christians, but as Edward Blum notes, white supremacists embraced it, because it gave them a kind of moral cover.

?Speaker 10: The Ku Klux Klan actually had documents and pamphlets that presented Jesus as white and his disciples as clansmen. Clansmen depicting themselves as followers of Jesus is really what enabled them to think they were doing the right things.

[background audio]

?Speaker 10: They saw Jesus and Jesus's disciples as white, as trying to further a white racial agenda, a purity agenda.

Eloise Blondiau: The KKK wasn't the first group to enlist Jesus in support of white supremacy, even if Sallman's portrait made it easier. The arguments for the God-given superiority of the white race backed by Bible quotations was cited to defend slavery and the mass murder of indigenous people. It's not hard to see how white Jesus bridged the dissonance for white families who gathered to watch the lynching of Black men, before skipping off to church. In Europe, Nazi theologians argued Jesus was not Jewish, but actually Arian. In '50s America, white Jesus was used to support segregation.

?Speaker 10: They actually put images of white Jesuses on their pamphlets. Their calls for organizational meetings to oppose brown versus the Board of Education. They made the claims that this white Jesus who was in favor of racial purity, was strongly against interracial marriage, something that would happen if young people were brought together in schools. The ties between the white Jesus and these white purity movements are there throughout the 20th century.

Eloise Blondiau: Dylann Roof who murdered nine Black Christians at a Bible study in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, drew white Jesus in his prison journal. Marquette University's psychology professor, Simon Howard, recalled seeing white Jesus in his great grandmother's house.

Simon Howard: I loved going to her house, just, one, because she was an amazing individual in person, but also, she had a lot of different figurines and things on a dresser board, but she also had pictures of family members. I remember seeing this one white man repeatedly. I'm like, "Who's this white guy in our family?" Learning later that this was Jesus.

Eloise Blondiau: It wasn't until he watched the biopic of Malcolm X starring Denzel Washington, that Howard realized why the white Jesus picture bothered him.

Speaker 11: History teaches us that Jesus was born in a region where the people had color. There is proof in the very Bible that you ask us to read.

Simon Howard: How do we arrive at this physical representation? Where did it come from?

Eloise Blondiau: As he got older, Howard read up on the Black Power movement. He heard speeches by Malcolm X denouncing racism in evangelical churches.

Malcolm X: You go inside a white church, what are they preaching? White nationalism. They got Jesus white, Mary white, God white, everybody white, that's white nationalism.

[laughter]

Eloise Blondiau: As a psychology student, Howard realized no one had ever studied how white portrayals of God and Jesus actually influence how people see the world. Eventually, he did his own study, assessing bias with a computerized test called an RIAT, a Raised Implicit Association Task, which measures attitudes towards race. He then presented subjects with various images, white Jesus among them, and afterwards, measured that bias again.

Simon Howard: When people are exposed to images of a white Christ, it makes those implicit associations more pronounced, which means that they had a more pro-white bias after being exposed to an image of a white Jesus.

Eloise Blondiau: Exposure to white Jesus pictures actually intensifies the view that white people are better than Black people.

Simon Howard: White supremacy is the ideology that is both conscious and unconscious. I don't mean that as a white supremacist in a white sheet running around terrorizing, burning crosses, but an ideology that associates whiteness with superiority and Blackness with inferiority. This image reinforces that ideology consciously and unconsciously.

Eloise Blondiau: Howard and every other critic of the image I spoke to, are not calling for forced removal. They just want churches to think more deeply about the impact of these portrayals of Jesus. They're especially concerned about depictions of white Jesus in Black churches.

Simon Howard: When we have these images that we worship, and Black people are the most religious group in the US and have been for a long time an overwhelmingly Christian. What I would say for these Black individuals is if you don't want to get rid of the white one, put a black one up there next to the white one. This is primarily thinking about children because now, they're not just solely associating godliness with whiteness. There's a more complicated picture that's being painted.

Eloise Blondiau: Remember, Mbiyu Chui, the pastor in Detroit, his church displays no white Jesus. A mile down the street from the famous statue, which still bears its painted black skin, is the shrine of the Black Madonna, which showcases a mural of Mary with deep brown skin holding a dark-skinned baby Jesus. Chui saw that image for the first time when he visited the church at 15.

Mbiyu Chui: It just felt right. It was like a revelation. I said, "Oh, wow, I never even considered the idea that Jesus could had possibly been Black. Wow. Who could have thought of this?" [laughs] Jesus was a man of color. We're just correcting the historical mistake.

Eloise Blondiau: The Shrine of the Black Madonna was founded in the '60s by a Black Christian nationalist, Albert Cleage Jr., who asserted that historically, Jesus was a Black man with ties to Africa. Other thinkers like James Cone, were more interested in how imagining Jesus hanging on the cross as a Black man being lynched, could bring Christians closer to understanding God.

Kelly Brown Douglas: To claim that Christ is white is indeed an anathema, is a betrayal of this God who has created us all as sacred beings and has promised us all a just future.

Eloise Blondiau: Reverend Kelly Brown Douglas, Episcopal priest and theologian and author of The Black Christ.

Kelly Brown Douglas: Why is it a betrayal of that? Because whiteness reflects what it means to be a part of an oppressive culture in reality. We would be suggesting that God is on the side of those who oppress. That God is on the side of white supremacists.

Eloise Blondiau: Unlike Cleage, Reverend Brown Douglas doesn't think Jesus was literally a Black man. The symbolism is what she's after.

Kelly Brown Douglas: Where would the crucified Christ be today? You could see Christ in the face of a George Floyd as he cried out, that said he couldn't breathe. That reminded me of Jesus from the cross crying out and saying, "I thirst."

Eloise Blondiau: Religious images invite believers to draw closer to God. They can also represent a worldview. Jesus has been imagined as George Floyd, as a Native American, a man with AIDS, the list goes on. Why aren't there more churches like Chui's? His Church has an outpost in Liberia, where there was a lot of pushback when he bought them prayer cards featuring Mary and Jesus with dark skin. They had never seen images like that before. They too had grown up with images of Jesus as white.

Mbiyu Chui: It's hard to go against what you've been conditioned to believe, especially as it relates to religion. It's hard, it's really hard. You can teach kids, but you can't teach adults what they think they already know.

[music]

Eloise Blondiau: Look, if every white Jesus picture disappeared overnight, America's white supremacy would remain. We know from Dylann Roof, back through all America's history, and from a raft of psychological research, these pictures do matter. If the first image Christian kids see of Jesus is a white one, it might take them their whole lives to unlearn it if they ever do. For On the Media, I'm Eloise Blondiau.

Speaker 1: That was this week's midweek pod, which first ran on the show a couple of months back. From all of us at OTM, have a Merry Christmas or whatever it is you celebrate. Don't forget to tune into the big show this weekend, when we look back on this terrible horrible year and find revelation and flashes of redemption.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.