The Trump Case Against E. Jean Carroll and The Progress of #MeToo

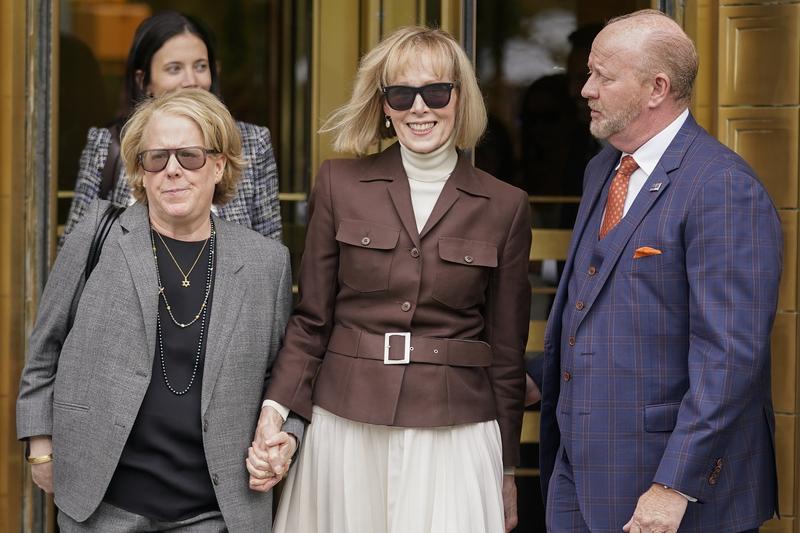

( John Minchillo / AP Photo )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Just a heads up, this conversation has a description of a sexual assault, so take note if you'd rather not hear that. This week, another legal blow for former president Donald Trump.

Reporter: Federal judge dismissed former president Trump's counter-defamation lawsuit against E. Jean Carroll. This happened earlier today. She's the woman who won a civil case against Trump earlier this year, alleging he sexually abused her. That alleged incident took place in the fitting room of a luxury department store in 1996.

Brooke Gladstone: Carroll was awarded $5 million in that civil case about Trump's alleged sexual abuse, but in a tit for tat, Trump sued right back, claiming Carroll had defamed him in comments she made to the media following her case. This week, Judge Lewis Kaplan ruled that Trump had not proved that Carroll's statements after the verdict were false or "not at least substantially true".

Just after the original verdict against Trump, I spoke with Rebecca Traister, a writer-at-large for New York Magazine, an author of Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger. She said the fact that the former president was held accountable for a nearly 30-year-old case underscores just how long it takes for a movement to change laws and lives. The verdict also suggests that last year's concerns about the death of Me Too were, to coin a phrase, greatly exaggerated.

Rebecca Traister: I think last summer was a moment where a lot of people said, "Look, this recent feminist resurgence that took place in part in reaction to the election of Donald Trump is at its endpoint." First, there was that Amber Heard-Johnny Depp trial, which was, in fact, really depressing. The treatment that Amber Heard got from the media and the public. Of course, last summer it was also in the wake of the Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

The Dobbs decision was 50 years in the making, but it happened to happen last summer in the same period that there was the Heard-Depp trial. I think it led a lot of feminist commentators to say, "This is it. Now, it's over. The backlash is here."

Brooke Gladstone: You say it's not dead. In fact, it may have taken E. Jean Carroll a lifetime to internalize the changes that have been happening around her for decades.

Rebecca Traister: In part, it's those of us who work in the media, and I include myself in this. We always want to be taking the temperature of where things are. We're constantly saying, "Is it going well? Is it going badly?" We're looking at what's happening this week, what happened last year, what happened in this administration, and we lose the broader historic view. A lot of people would pinpoint Me Too to October of 2017 with a reporting on Weinstein.

In fact, exactly a year before that had been the release of the Access Hollywood tape in which Donald Trump, who was then on the verge of being elected president was recorded bragging about grabbing women against their will.

Brooke Gladstone: Many people will argue it didn't seem to have an impact.

Rebecca Traister: People forget that after the release of the Access Hollywood tape, there was an online outpouring, thousands of people talking about how they themselves had been grabbed against their will. It was a real precursor to what happened virally a year later in 2017. Let me take it back one step further. The summer before the Access Hollywood tape, there had been reporting in New York Magazine, by the way, about Gretchen Carlson and her allegations against Roger Ailes.

That was a story about sexual harassment that had a real impact on Roger Ailes himself on Fox. It's action, reaction, action, reaction, and neither victories nor losses are the end of this story because you have that outpouring in response to the Access Hollywood tape, and that is in October up through early November of 2016. Then Donald Trump won via the Electoral College.

People were so livid that he got elected in the context of it being after these revelations of his assaults. I would argue that absolutely helped to energize, in January of 2017, the Women's March, which at the time was the biggest single-day demonstration in the country's history. That absolutely was informed by the release of the Access Hollywood tape, by the women who had told their stories at that point.

A historic number of women winded up being elected to office in the fall of 2018 following the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh, which is also unsuccessful in that Kavanaugh gets confirmed, and yet Democrats win a historic election in 2018, a historic number of women and first-time candidates. I don't want to convey a kind of denial of the losses. It really matters that Brett Kavanaugh is on the Supreme Court.

It really matters that Donald Trump was president and could be president again. It really matters that Clarence Thomas still sits on the Supreme Court despite the obviously believable testimony of Anita Hill in 1991. These losses are real, and they do long-term damage, but they also spawn reactions, which are just as real.

Brooke Gladstone: I think that was why we were so excited by your column because you wrote, "The most important steps towards greater gender equality are rarely about the bad men or what happened to them at all. That this is about what the women do, how they present themselves, their courage, their way of changing perception in the conversation." That's what I want to talk about. E. Jean Carroll's testimony was made possible by the Adult Survivors Act, which was signed by New York Governor Kathy Hochul in May of 2022.

Rebecca Traister: That was pushed for over years by activists in the wake of Me Too, in the wake of the election of Donald Trump, and anger burst forth a day into his presidency with the Women's March. A year into his presidency, the #MeToo explosion that came in the wake of the Weinstein reporting, E. Jean Carroll did not publish her story until 2019. Social progress happens over lifetimes, not seasons.

Brooke Gladstone: What is the significance of the fact that this assault was considered and judged via a defamation trial?

Rebecca Traister: That's a big deal because Carroll's testimony herself is that when she called her two friends back when this assault happened, one friend advised her to go to the police, and the other friend said, "Don't, he'll bury you." He was a celebrity in New York City. He was a real estate tycoon. Donald Trump has been a powerful public figure for many decades, and what her second friend advised her to do that she listened to at the time was to stay quiet because that was an assessment of the power differential.

Now, 30 years later, the defamation suit, that was her legal option because as far as a criminal charge of sexual assault goes, her statute of limitations was up. She pursued the defamation case, which is a very powerful message to people saying, "Wait, actually, I'm not going to let you bury my voice. I am going to come after you, and I am going to fight for the veracity of the story that I told." She said several times during the trial that she was just happy to be in court telling her story.

Brooke Gladstone: Writing in Slate, Dahlia Lithwick said that, "Finally, the good victim trope really seems to be faltering, whether it's Stormy Daniels chortling about the former president's penis, E. Jean Carroll refusing to designate herself a rape victim while still suing the former president for rape, or Amanda Zurawski testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee about how her inability to access health care nearly killed her. These women are not broken, defiled, ruined, or asking men to rescue them. They are rather pissed off living their lives and defying the public imperative to open a vein in public as a testament to their loss and brokenness. They are nobody's property, nobody's responsibility, and it's about freaking time we took them seriously." What defines that notion of a good or acceptable or even more importantly, plausible victim?

Rebecca Traister: Historically, the perfect victim, as Dahlia wrote, is white, timid, vulnerable, traumatized. Their experience of whatever they're alleging has defined their entire existence. The idea that somebody could be brassy, could continue in E. Jean Carroll's case to give assertive advice to other women, that she could continue to shop at Bergdorf's, that she didn't scream. First of all, a lot of those behaviors are what we understand to be completely in line with people who have been sexually assaulted or harassed and engage in all kinds of nonlinear behaviors afterwards.

Brooke Gladstone: On May 5th, there was a remarkable letter in the New York Times. The woman named Sandy McDonald wrote a response to Jessica Bennett's opinion piece called Questions Not to Ask a Rape Accuser. McDonald wrote, "I didn't scream when I regained consciousness while being raped by a boy who was part of a group of exchange students newly arrived in Southern Vermont. I offered them a ride to their dorm from the Brattleboro Bar where I worked, and as thanks, they invited me in for a glass of wine they'd brought from their native country. I didn't scream when the room began to spin, awakening pinned.

I didn't scream when I heard other boys pounding on the door. 'They just want their turn,' the boy on top of me said. I didn't scream to protect myself from further rape. I told him I liked him best and wanted only him. I didn't scream as the dawn finally broke and I cautiously collected my clothes to walk naked through the snow to my car. I didn't scream when my gynecologist noted vaginal abrasions. I didn't scream when a cop I considered my friend told me not to bother to report the rape, that I'd be the one scrutinized. Instead, I wrote a letter to the head of the exchange program concerned for the families that these boys were about to join.

I didn't scream upon receiving his elegantly worded response alluding to the boys' "completely inexcusable behavior." I didn't scream when I cashed the $40 check he'd drawn on the program's account to reimburse me for medical expenses. He marked it 'entertainment'. A half-century has gone by and I have never stopped screaming inside."

Rebecca Traister: I had not read that letter until I just heard you read it now.

Brooke Gladstone: Someone very dear to me didn't scream.

Rebecca Traister: Yes. Well, I have to tell you, I'm listening to this and I'm like, "I didn't scream either." One of the incredible things that E. Jean Carroll was so open about in her testimony and in the memoir is what people are made to feel when something like this has happened to them even if they know rationally that women are made to feel shame. I just heard her saying again that she felt so stupid for having gone in the dressing room with him. People who are assaulted reflexively feel it was their fault, there was a risk in screaming, that the revelation won't be that somebody's assaulting you, but that you've done something bad. Just pure human terror.

Brooke Gladstone: There's that other thing too that I've heard. You try and reinterpret it to be less horrible.

Rebecca Traister: Yes, you do.

Brooke Gladstone: Hence the giggling. Hence the joking. You just want it to not be what it was.

Rebecca Traister: Part of what an old version of a perfect victim entailed, that idea to be assaulted or attacked would somehow define or mark you, would be the whole of who you are is so terrifying for people because we've all been raised with those ideas. Even if we can rationally disentangle them from antiquated ideas about female virtue or whatever, that to have this happen to you would then define who you are, define how you move through the world, and when it happens to you as it happens to so many of us, in one way or another, part of the instinct is to say, "No, no, no, no, no. I'm not going to let this be important. I am not going to let this define me. I'm not going to let it shift my course.

I'm not going to let it shape who I am because it's an awful thing that just happened and I'm going to pretend that it wasn't important."

Or, "I'm going to make it not important. I'm going to make it not real by staying silent about it. I'm going to try to forget it. I'm going to press it down." A million things we do to make it not loom so large because it sucks that this stuff happens so often. E. Jean Carroll talks about how she's not been able to have a sexual or romantic relationship since. That's her story of how this shaped her life, but, oh, it's so awful that these things can have an impact and so a lot of us do the work to say, "No, I don't want it to have that impact."

The kind of magical thinking that we do, the kind of rational thinking we do to integrate this very common experience into our lives can take so many different forms, which, again, is the most basic challenge to this idea that there's one way to have been a victim, that there's one way to have behaved that makes you plausible or viable or valid. I want to take it back just for a second to some of the history we talked about earlier, having covered Christine Blasey Ford's testimony and having been shaped politically by Anita Hill's testimony.

Brooke Gladstone: In 1991 when she appeared in court to talk about sexual harassment from Clarence Thomas and was not allowed to present witnesses and was silenced.

Rebecca Traister: Both of those women only testified in part because they both had advanced degrees both class and professional peers of the men that they were accusing. They could rise to the level of being heard, even though then they were treated badly. Ultimately, their testimony did not impede the ascension of either man to the court. I think all the time about how many other women and men have been harassed or assaulted by people sitting in positions of tremendous power but whose stories could never get that public hearing because they are imperfect in other ways.

People who worked in the service industry, people who would be discounted because of the way they were dressed and whose stories are no less real. But because they don't fit an incredibly narrow view of the voices we are encouraged to take seriously and understand is legitimate, those voices are never heard.

Brooke Gladstone: How do you put E. Jean Carroll's case in the history of Me Too?

Rebecca Traister: I think it's a really interesting watershed moment because it excavates so much history in both short-term and long-term ways. Short-term, with regard to this explosive political period that maybe began in the summer and fall of 2016 with the Access Hollywood tape, the revelation that a presidential candidate had admitted to grabbing women against their will, that that did not, in fact, impede his victory, the kind of anger that that provoked.

Then the explosion of the #MeToo movement from which came E. Jean Carroll's memoir from which came the Adult Survivors Act pushed by activists to reopen a window of legal accountability after the statute of limitations. You can see the very recent push-pull winding progress that leads to seven years, eight years later, the first instance of legal accountability that Donald Trump has faced. It comes from layers of recent history that got to this moment. It is such an incredible lesson and view of the stop-start circuitous nature of how this happens communicatively, legally, politically.

More broadly, E. Jean Carroll's willingness to talk about being born in 1943 gives us a view of an even longer history than that and takes us back to pre-second-wave feminist ideals in which she came of age. Any of the legal protections that were won in the 1970s in which the things she was raised to understand about sexuality, shame, assault, her own responsibility, her own ability to speak out were just wildly different from the kinds of tools and supports that are imperfectly available to her now, and so that's the longer view of history that she so generously gave us.

It has been, I hope, just a moment in which the arduousness of this process has been broadly revealed, but also the potential for success even in the wake of failure because it's a really important lesson for all of us that there are no easy stops or starts and no clean neat stories at this process when it comes to fighting for all kinds of equality and inclusion. It's a lifetimes project for all of us. We can't rest easy after a victory, nor can we despair and become paralyzed after a defeat. This goes on and on.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much.

Rebecca Traister: Thank you.

Brooke Gladstone: Rebecca Traister is writer-at-large at New York Magazine and author of Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger. Thanks for tuning in to this midweek podcast. Be sure to check out the big show on Friday for a reflection on what has changed in mainstream coverage of transgender communities. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.