From Public Shaming To Cancel Culture

( flicker / Flickr-creativecommons )

Interviewer: Over the last couple of weeks, we've taken on some of the battles in the ongoing culture war. We looked at how a group with a right-leaning agenda weaponized the AP's adherence to neutrality to get a young reporter fired for her Twitter activism. We examine the issue of critical race theory, a term misapplied to classroom lessons about America's racist past and, of course, we talked about the granddaddy of them all, Cancel Culture. Michael Hobbs, co-host of the podcast You're Wrong About told us that there isn't a situation that's been labeled a cancellation that couldn't benefit from a more accurate word to describe what happened.

"So and so was fired." "Such and such was met with disagreement on Twitter." Cancel need not apply. He also explained on his own podcast with Sarah Marshall, that there were a few pivotal events along the way that led to the term cancel culture becoming the moral panic it is today. One of them was the 2015 release of Jon Ronson's book, So You've Been Publicly Shamed. It was a series of case studies of people who were, in a word, canceled before we even started using the word. When I spoke with Ronson in 2015, he told me that his investigation was triggered by his own discovery that someone had started using a Twitter account in his name, and with his face. An unknown entity that tweeted in a way that was utterly unlike Ronson.

Jon: Talking about how he was very much looking forward to having a dinner party and he's going to make some nice lemongrass stew. Anybody who knows me knows that I abhor dinner parties.

Interviewer: This was annoying, embarrassing even, but it wasn't exactly shameful. How did that episode lead you into ultimately, what became a deep exploration of shame?

Jon: Well, I asked these guys to take down their spam bot, and they refused. This went on for a couple of months. Finally, I said, "Look, what if you won't take down your spam bot," they kept calling us an info-morph, "Can we at least meet and you can explain the rationale behind your spam bot?" They said, "Yes, we'd very much like to meet to explain to you the rationale behind the info-morph." I said, "Good, because I'm really looking forward to finding out the inspiration behind spam bot."

I met them and, to cut long story short, I filmed them for an hour. We had a huge fight and then I put the video on YouTube and was dreading it because I'd lost my cool and I just thought everybody was going to mock my screechiness. In contrast, thousands of people left to my defense in the most visceral and eventually aggressive way.

Interviewer: These campaigns of vigilante justice online usually begin with reasonably voiced objections to the behavior at issue and end with death threats.

Jon: Yes, end with, "Gas them," which was literally one of the things that somebody wrote. I went from feeling thrilled and delighted that people all over the world were uniting to tell me that I was right and they were wrong, to starting to feel uneasy.

Interviewer: Right, but on the other hand, you were something of a fan and an occasional participant in social media's shame brigades and you offer some early examples of social media shaming, where greedy, exploitative people were shamed into doing the right thing. This was true democratic justice at work.

Jon: Yes, and still is to some extent. One recent example is the Black Lives Matter protests.

Interviewer: On the other hand, your book deals with a darker strain that emerged, a digitally-enabled mob mayhem. You start off with a couple of very different but also similar cases, that of Jonah Lehrer, and Justine Sacco. I wonder if you can take them one at a time.

Jon: Sure. Jonah Lehrer was a wunderkind pop neuroscience writer, started really young. Jonah said to me that what he had was a toxic mixture of insecurity and ambition and he felt it was going to end really quickly, which actually turned out to be quite prescient. That was, I think the reason why, but nobody would have known that.

Interviewer: The reason why he made stuff up and generally cut corners in presenting fascinating research that he couldn't support. Describe Jonah Lehrer's shaming.

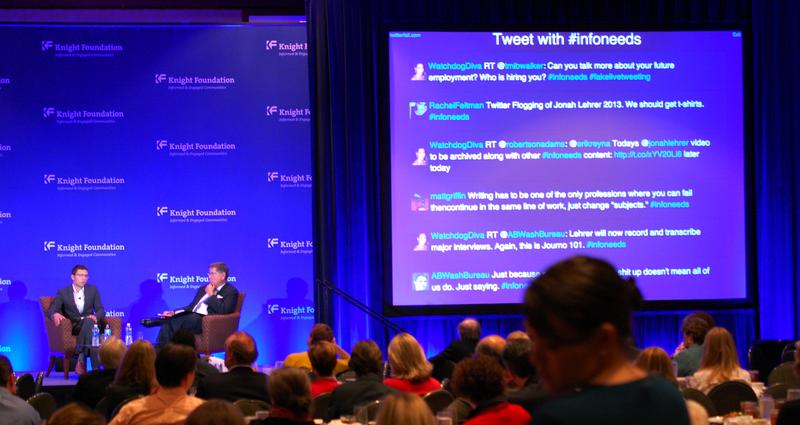

Jon: Jonah was fired from the New Yorker, obviously. His books were recalled and pulped. There was a lot of noise, a lot of editorials, and then it died down. Then he said he was going to make an apology at Knight Foundation lunch the following week, and the Knight Foundation's a journalists foundation. He asked me to read his apology speech and I did. What was interesting about his apology speech was that he'd put it in the context of a Jonah Lehrer speech about the neuroscience of-

Interviewer: Self-deception and lying and reconstructing reality to your benefit, that kind of thing.

Jon: Right. What the Knight Foundation had done was erect a giant-screen Twitter feed, huge, behind Jonah's head, and anybody could tweet their ongoing opinion of Jonah's quest for forgiveness, and their comments would appear huge right in Jonah's eye line. As Jonah was trying to apologize, he was seeing in real-time Twitter saying, "Jonah Lehrer is boring us into forgiving him." "Jonah Lehrer is just a frigging sociopath." "Jonah Lehrer is tainted as a writer forever." He was being told in the most visceral way that there was no way back in, there's no forgiveness. This is forever. Is that the world that we want, where you're swallowed up by the worst things you ever did? As opposed to put within a wider human context.

Interviewer: Which brings us to Justine Sacco.

Jon: I started to meet people who were similarly torn apart or, in fact, worse than Jonah. Torn apart for jokes that landed badly for nothing. For me, the saddest one was this woman Justin Sacco. She was in New York City PR woman with 170 Twitter followers, and a rather brittle way about her Twitter presence. She was traveling from New York to Cape Town and tweeting acerbic little jokes. "Weird German dude, get some deodorant. This is the 21st century." "Chili, bad teeth, back in London." Then the final leg, when she was at Heathrow she tweeted, "Going to Africa, I hope I don't get AIDS. Just kidding. I'm white."

Interviewer: Taking that apart. It's clear that she doesn't think white people are immune to AIDS. She's making a tin-eared joke about white privilege. She tweets. She gets on the plane. This is incredible.

Jon: She chuckles to herself when she wrote this joke, presses send, goes to sleep. Wakes up 11 hours later in Cape Town, turns on her phone. Straight away there's a text from somebody she hasn't spoken to since high school. That said, "I am so sorry to see what's happening to you." She looked at it baffled and then her phone, she said to me, just exploded with texts and alerts. Her best friend, Hannah, "You need to phone me immediately. You're the worldwide number one trending topic on Twitter right now." What had happened was that one of her 170 followers had sent the tweet to Sam Biddle, who's one of the main guys at Gawker, and he retweeted it to his 15,000 followers and that just went viral within an hour or two of her just stretching out in her seat.

Interviewer: Tell me about how her life changed in that transatlantic flight?

Jon: Well, at first it was philanthropic people saying, "In the light of this disgusting racist tweet, I am donating aid to Africa." This is following then the old pattern of, "Let's do something good." Then that changed, the trolls got involved. "Is it terrible of me to hope that Justin Sacco gets AIDS lol?" An awful lot of ones like that. Then celebrities got involved, like Donald Trump found it hilarious. Then people started to call for her to be fired. Eventually, her employers got involved and it said this is an outrageous tweet, employee currently on an international flight.

That's when everything changed because it became hilarious to hundreds of hundreds of thousands of people just like us that this woman was being destroyed and she didn't know it. We knew something that she didn't know. A hashtag began to trend worldwide, "Has Justine landed yet?" There were countless tweets like, "Oh man, I can't wait to see when Justine Sacco turns on her phone," et cetera. There's a thing in torture called the Bucherer effect, where the holy grail, somebody told me, of exotic interrogation techniques is to debilitate somebody by startling them in a profound way. I think that's what we on Twitter learned to do that night.

Interviewer: You started to think about the nature of mob mentality. We've all heard about the research that people's better selves are extinguished when we assemble into mobs, and the lizard brain emerges. In an especially great chapter, you discovered gaping holes in that mob mentality research. I wonder if you could briefly summarize what we thought we knew and what we don't?

Jon: Sure. Whenever the crowd gets frightening, we bring out the phrase "Group madness." Obviously there's a certain amount of this stuff that goes on, but turns out that group madness goes back to a guy called Gustave Le Bon, who is 19th Century person.

Interviewer: Lovely guy.

Jon: He wanted to be accepted into the Parisienne elite. He was nouveau riche. He did this huge study measuring brains, and came up with the theory that white, prosperous men have the biggest brains.

Interviewer: Women are barely above lemurs in his assessment, but what does that have to do with mob mentality?

Jon: Well, so eventually he worked out that the crowd, like women and children, were sub-human. That man loses himself in a crowd, and utterly loses their free will and becomes like a grain of sand amid other grains of sand. People loved it. This book came out, The Crowd, which was hailed by Mussolini, and Goebbels. Basically formed our opinion of how people behave in crowds for 100 years. To this day, in fact just before I moved to New York there was this big riot in London, the London riots. It was very frightening. Everybody was starting to evoke these ideas of Gustave Le Bon.

It's like these people have been infected by a virus, which means that they have no free will. I was hearing all this on the news. The riot was getting closer and closer to my house, and I was terrified. We locked all the doors, and we're staring at the TV. It was getting closer and closer, but we lived up a hill. What happened was the riot stopped at the bottom of the hill.

Interviewer: Somehow, this mob gained enough native intelligence not to climb a hard hill in bad weather.

Jon: Right, exactly. That didn't sound like they were infected by virus to me at all. I think they made a very lucid decision, which is the decision that I try and make whatever I can, of not climbing the hill.

Interviewer: Can you take us through the prison experiment that has formed so much of our assumptions about mob behavior and what you learned about that?

Jon: One of the main reasons why Le Bon's theories still live on is because of Philip Zimbardo, the social psychologist who created the famous Stanford Prison Experiment. He got a bunch of students, put them in the basement, replicated a prison environment with half of them as guards, half of them as prisoners. Six days later abandoned the experiment because it had all gone to hell. The guards had become evil. They'd been infected, just like Le Bon's theories. They'd been infected by this evil environment. They'd become mindless, like zombies.

Interviewer: Regular, nice, middle-class boys turn into psychopathic creeps.

Jon: I tracked down some of the guards from the Stanford Prison Experiment. They were really upset actually, about the way they've been portrayed all of these years. This one guy John Mark said, "It gets taught in my daughter's school, and it's really upsetting to me." I said, "Why does it?" "Because it was nothing like that at all." He said when you're thinking about the Stanford Prison Experiment about the people turning evil, you're really only thinking about one man, and that's man called Dave Eshelman. It's true there's been papers written about Dave Eshelman that as he got more evil, his voice changed into a Louisiana accent. That's how evil.

[laughter]

Interviewer: You spoke to him?

Jon: Yes, and he said, I was watching Cool Hand Luke. He said, "I was acting." He said Philip Zimbardo was right there in the middle of it. We knew what he wanted because he told us. He wanted us to be bullies and to stress that out as much as possible. He said, "Honestly, I thought I was doing something good," which is the opposite of evil.

Interviewer: Now, on the other hand, the guy was clearly a major loon in the way he behaved, and he was quite cruel. You could argue he brought that with him into the experiment. It wasn't the experiment that made him that way.

Jon: Yes, or even that these were the times and they were prison riots all over the place. In Massachusetts Walpole prison was rioting all the time. This was the ambiance. I put all of this to Zimbardo, and he emailed me back to say I was being given a completely naive. John Mark, one of the other guards, said that Zimbardo has never released the full footage. Has only released these choice moments where Eshelman is being particularly brutal. When you watch these moments, as I did, they're hammy.

Interviewer: That really comprises the first section of your book. You examined are we wired to create these vigilante mobs to shame people, and you decided that we aren't necessarily wired. Right? Then you transition to the next section, which has to do with what happens when you are shamed. One of the great insights that you make, and then you back away from, you use this guy named Max Mosley.

Jon: Yes. Max's father was the head of the British Union of Fascists, but I think probably felt pretty jealous of Hitler and Mussolini.

Interviewer: Right, and Max's mother was a Mitford.

Jon: Yes, in love with Hitler. Anyway, so Max manages says to shed this very dark legacy becomes the head of Formula One Racing's governing bodies. Becomes really successful. Then a few years ago, somebody phoned him up and said, "Have you seen the News of the World?" It was a picture of Max naked in what the News of The World called a sick Nazi orgy.

Interviewer: He sues The News of The World, and he wins a defamation suit because it turns out it was German, but it wasn't Nazi. It was kind of on a technicality, but that's not the real point. The point is, he goes, "Yes, I like that kind of sex." This is when you had this profound insight. You theorize that perhaps, and I quote you, "Our shame worthiness lies in that space between who we are and how we present ourselves to the world." He said, "Yes, I like this S&M B&D stuff. Sue me. It's not illegal."

Jon: Jonah did the absolute opposite. Jonah maintained in the light of overwhelming evidence that he was being extremely unprofessional, pretended that he was more professional than anybody else. Max said, "Look, everybody knows that when it comes to sex people think and do and say strange things. Only an idiot would think me the worst for it."

Interviewer: You changed your mind.

Jon: I did change my mind.

Interviewer: You realize there's a bunch of factors other than just not being ashamed.

Jon: This was the insight that I found actually really chilling when you think about it, because lots of unashamed people still get shamed. What is it? Finally, after months and months of thinking about this, I came to the conclusion that the real reason why Max Mosley survived his shaming was that there was no shaming. We just didn't care. If you're a man in a consensual sex scandal, who cares? What it means is that on Twitter, we have total control over people's destiny. We on Twitter have decided Max Mosley, that's fine. We don't care. Justin Sacco, she's dead.

What I find so interesting is that we haven't woken up to that realization about ourselves. We still like to see ourselves as the hitherto silenced underdog fighting the good fight. The Rosa Parks. We have insane amounts of power right now, because what's the worst sin now? The worst sin now is a misuse of privilege. Now, of course a misuse of privilege is a worse sin than a consensual sex scandal, but we're tearing people apart for our perceived idea. A misuse of privilege is getting wider and wider and wider as a concept.

Interviewer: That's right. Now, I want to go to the penultimate part of the book, which is a profound exploration of the nature of shame. A lot of this insight comes by way of a psychiatrist named James Gilligan. He was a Harvard-educated psychiatrist. He started examining homicidal prison population. Ultimately, he found that universal among the violent criminals was the fact that they were keeping a secret, and that secret was that they felt ashamed, deeply ashamed, chronically ashamed, acutely ashamed. As children, these men were shot, axed, scalded, beaten, strangled, tortured, drugged, starved. I'll end quote there and just say that it would inevitably give rise to the extreme behavior they took part in as adults.

Jon: Right. He said this line that's followed me around, I think it's one of the most profound things anybody's ever said to me. He said, "All violence is an attempt to replace shame with self-esteem." I feel in that moment, other than the tiny minority of people who have a new illogical absence of empathy, that feels right to me. Yet, here we are. I think what a lot of people forget was when Twitter began, it was the opposite of how it was now. It was actually a radical de-shaming exercise. People would blab out their hitherto shameful secrets because, as James Gilligan's research shows, shame internalized leads to horror. Shame let out leads to freedom, or if nothing else a funny story.

That's what people were doing on Twitter. It was a wonderful thing, and then what do we do with it? We started to use it against ourselves and created this cold brittle conservative thing, when if somebody admits their shameful secret we destroy them for it.

Interviewer: As you wind down, you talk about what's the solution at least to online shaming that can destroy lives. You talk about a lovely person who worked with the disabled and whose life was destroyed.

Jon: Loveliest. Just the most ordinary person in the world, her name's Lindsay Stone. She used to have this running joke with her friend Jamie, where they would make fun of signs. Smoking in front of a no-smoking sign and so on. They went to Arlington, the tomb of the unknown soldier and, as she said to me, inspiration struck. There's a picture of her in front of the silence and respect sign and she's flipping the finger and pretending to shout. Again, much like Justine, not the best joke in the world. Nobody's saying that it is, but she posted it on Facebook and then a month passed, nothing happened. Then suddenly it went viral and she was fired and became agoraphobic, deeply traumatized, felt utterly worthless. There's nothing worse. I can really tell you this. Something that people don't realize is that being publicly shamed, the very nature of who we are as human beings.

Interviewer: You suggest it's a kind of death. Gilligan said that, that the word mortification means to deaden.

Jon: To be told that you're worthless and you're out of society, like Jonah in front of that Twitter feed.

Interviewer: How do you fix this?

Jon: Well, there's a team of people in San Francisco, a company called reputation.com.

Interviewer: I want to say, full disclosure, they have been a sponsor of this program at some point. They have nothing to do with this interview.

Jon: Unfortunately, it costs a hell of a lot of money. It will cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to correct the mistake that Lindsey Stone made.

Interviewer: You decided to cover what they did for your book. They wanted a subject, you landed on Lindsey Stone.

Jon: It's the only way that she would agree to talk to me too, because she was just too traumatized to tell the story. I offered her quite the incentive, which I've never done before I should just say. I didn't know whether it was a good thing or a bad thing, but it's what I did. It really worked wonders, but the really sad thing about is I'd listen in on these conference calls between Lindsay and reputation.com. Basically, what they do is try and replace the silly, impudent, foolhardy mistake that she made with pleasant banalities. "What's your favorite type of ice cream? What do you think about Lady Gaga's new jazz album?"

Interviewer: On unobjectionably bland human being. A Donna Reed for the internet.

Jon: Because we have created a world where the smartest way to survive is to be bland.

Interviewer: It worked.

Jon: It worked.

Interviewer: Her objectionable picture fell down in the rankings until, of course, the end of February when your Guardian feature came out about your book. The photograph was there again and now it's back .

Jon: It's true that when my book extract came out, it certainly went back again. I asked her, I said, "What do you think about that?" She said that talking to me was very cathartic and she also felt that it's really important to be part of the discussion, which she is. I think that Lindsay's story and Justine's story in my book might actually change people's behavior. Not think twice before you tell it an impotent joke, but think twice before you destroy somebody for telling an impudent joke.

Interviewer: You conclude by saying, "I personally no longer take part in the ecstatic public condemnation of people, unless they've committed a transgression that has an actual victim." You've noted that there usually isn't a victim.

Jon: I don't think that's the perfect ending. The other day, I did an interview and the interviewer said, I'm totally paraphrasing, but effectively they said something along the lines of, "You're right. People should be allowed to make risque jokes." For instance, there was somebody the other day making fun of a transgender person, called them a fruit loop. "What's wrong with that?" Actually, there is something wrong with that.

Interviewer: It isn't about feel free to be as objectionable and offensive as you want.

Jon: Don't disproportionately tear somebody apart for a transgression that barely matters. That doesn't mean feel free to insult whoever you want. That's the opposite of what I'm saying because, of course, when you insulted transgender person you're shaming them. That's what you're doing. I think, think twice before gleefully condemning somebody for doing almost nothing wrong.

Interviewer: You said that you missed the fun a little, but it feels like when you became a vegetarian, you missed the steak, although not as much as you anticipated, but you could no longer ignore the slaughterhouse.

Jon: Because I've met so many of these people now who've been destroyed in this way and it's agonizing to meet them. We have no idea how severe our punishments are.

Interviewer: Jon. Thank you very much.

Jon: Thank you.

Interviewer: Jon Ronson is the author of, So You've been Publicly Shamed. This conversation first aired in 2015. Thanks for listening. Check out the big show on Friday. We usually post around dinner time.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.