Presidential Debates: Yay or Nay?

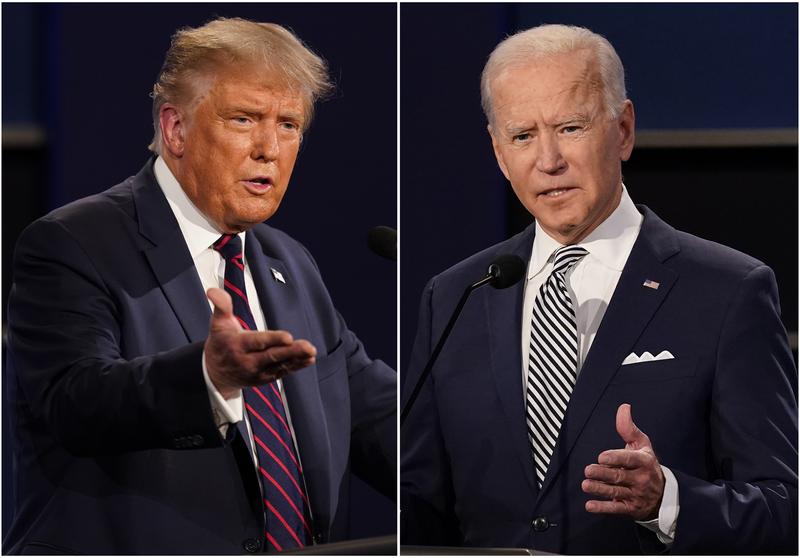

( AP Photo/Patrick Semansky )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On The Media's midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. According to the New York Times-Siena poll released this week, 54% of Republican voters said that if the election were held today, they'd vote for Donald Trump. Ron DeSantis trails by 37 percentage points, and the others in the field are in single digits. Despite or because of his solid lead, Trump is unclear as to whether he'll show his face at the first Republican debate set for August 23rd. As he told Maria Bartiromo on Fox--

Donald Trump: We have a lead of 50 and 60 points in some cases. You're leading people by 50 and 60 points, and you say, why would you be doing a debate? It's actually not fair. Why would you let somebody that's at zero or one or two or three be popping you with questions?"

Brooke Gladstone: Trump's debate snubbing is just the latest example of the GOP resistance to a longstanding political norm. Last year, Ronna McDaniel, chairman of the Republican National Committee, wrote a letter to the Commission on Presidential Debates, the independent bipartisan organization that has convened general elections since the '80s. In her letter, she said that the RNC would boycott the upcoming presidential debates unless the commission were willing to meet its demands. Between those demands and the possible absence of the front-runner, the question is, what, if anything, would be lost if the presidential debates didn't happen? I spoke to Alex Shephard, senior editor at The New Republic, last year after he wrote an article titled, Let the Presidential Debates Die.

Alex Shephard: For the last 10 years, more or less, the Republican National Committee has been complaining that these debates implicitly favor Democrats, largely because they say that moderators with connections to the Democratic Party, most notably George Stephanopoulos, are favored over moderators that might have more Republican leanings, but they also I think want to stop what they see as the slow growth of fact-checking in these debates, and this began in 2012 when Candy Crowley, moderating a debate between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, stepped in to gently correct Mitt Romney.

Mitt Romney: Record because it took the president 14 days before he called the attack in Benghazi an act of terror.

Barack Obama: Get the transcript.

Candy Crowley: He did in, in fact, sir. Let me call it an act of terror-

Barack Obama: Can you say that a little louder, Candy?

Candy Crowley: -[unintelligible 00:02:36] use the word. He did call it an act of terror.

Alex Shephard: A moment that led to multi-day television or cable news cycle of just absolute outrage and invective on the right about how this was just another instance of the liberal media hating conservatives on the right and trying to tip the scales in favor of Democratic candidates, but that has shifted, I think, really substantially since 2016 when Donald Trump, in particular, both on Twitter and in interviews and other public statements, has insisted that debate moderators were out to get him.

Brooke Gladstone: They've had Chris Wallace on that side. Is that not Fox-ian enough? He was a Fox guy then.

Alex Shephard: Chris Wallace we know is probably the debate moderator who Donald Trump objected to the most during this period. They don't like the moderators that are being chosen. They don't like the last-minute changes that were made in the last cycle, even though, again, those last-minute changes were made because Donald Trump, their candidate, caught COVID and was infectious, and they're using this as a way, I think, to undermine the commission's authority, so they can then either go around and try to start a new organization that they think will ultimately be more beneficial to them or to just scrap the entire debate structure altogether.

Between 1976 and 1988, these debates were run by the League of Women voters. The two parties had an enormous amount of leverage over who, for instance, got to moderate the debates. They could essentially each reject any moderator that was suggested. In 1984, for instance, over 100 potential journalists were rejected. Now, this level of control is not good for either debates or democracy. The idea behind the Commission on Presidential Debates was essentially that you would have a bipartisan commission come together and they would solve these problems in conversation with the two parties. Now, I think what's happened over the last decade is that Republicans have decided that that bipartisan commission itself is just simply not good enough. It's doing too many things that benefit Democrats.

Brooke Gladstone: It's your view that the RNC's objections to the way that presidential debates are handled now largely mirror its complaints about the mainstream media in general.

Alex Shephard: Yes, and it's one reason why it's difficult to summarize their actual objections because they're vague. They involve Republicans not being consulted enough, that their influence isn't great enough, that, comparably, Democrats have more control over the process. This is, I think, eerily similar to the kind of arguments that Republicans have been very successfully making about the "mainstream media" for decades now, right? That the media just has an implicit Democratic or liberal bias and that it does not favor Republicans and that the only way to respond to this is to create a counterbalance. Now, you have that in terms of Fox News and now, numerous other places on the right, like One America News, et cetera.

Brooke Gladstone: Some quick history, okay? Presidential debates were started by Senators Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas in 1858. They're remembered as the great debates, but it didn't become a political norm until about 100 years later. Run us through what did they yield over the years? How have they evolved or devolved, as it were?

Alex Shephard: The idea behind these debates has always been this old, Greek idea about rhetoric, that to be a great statesman, you must also be a great speaker. One reason why the Lincoln-Douglas debates are remembered so fondly is this idea that these were two master rhetoricians at the top of their game going at each other about the most important issues of the day, but--

Brooke Gladstone: Also, nobody actually heard them.

Alex Shephard: Correct. They mostly--

Brooke Gladstone: Or hardly anybody.

Alex Shephard: If you were lucky enough to be living in Illinois in 1858, then maybe you saw these, but for the most part, they were circulated in print form. The 1960 presidential debate between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy is seen as this moment in which television took the foreground.

John F. Kennedy: I think Mr. Nixon is an effective leader of his party. I hope he would grant me the same. The question before us is, which point of view and which party do we want to lead the United States?

Moderator: Mr. Nixon, would you like to comment on that statement?

Richard Nixon: I have no comment.

Alex Shephard: Famously, people who listened to the debate on radio thought Nixon won, but people who saw him noticed that he was very sweaty and decided that the handsome senator from Massachusetts was the better candidate, but they don't start happening regularly until 1976 when Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford have three debates. These are marred by a series of technical difficulties and other problems, including a famous 27-minute silence in which both candidates stood completely still the entire time because they didn't want to look weak.

Brooke Gladstone: Yikes.

Alex Shephard: These type of errors largely followed the debates when they were run by the League of Women voters, which controlled them for 12 years, from 1976 to 1988. Then from there, you have the Commission on Presidential Debates. During this period, there are very few instances in which you can think of substantive policy discussion happening. The most famous moments are almost all personalities, or they're zingers. It's Ronald Reagan.

Ronald Reagan: I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience.

Alex Shephard: In 1992, George H. W. Bush looks at his watch when asked a question. The moment in the 2012 debate between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, in which he was asked how he was going to staff his campaign.

Mitt Romney: I went to a number of women's groups and said, "Can you help us find folks?" They brought us whole binders full of women.

Alex Shephard: This setting one of the first really viral moments of presidential debates, but did it actually tell us anything useful? I'm not sure that it did. I think that that gets to another point as well, which is if you think about these debates as being about informing the public or swaying them, they've certainly failed to do that. By the time these debates are happening, also, voters have already made up their minds about who they're going to vote for. One reason that clip took off was not that a light bulb went off in undecided voters' head, and they said, "Hey, wait a second, this guy, Mitt Romney, these binders full of women, I don't know if I can vote for him." It was because the tens of millions of people who had already made up their mind to vote for Barack Obama saw this as a gaff, got on Twitter, and made a lot of jokes about it.

Brooke Gladstone: You say that the use of the debate historically has been to show a contrast between the candidates. The theory was you would get a hyper-distilled version of the candidate's plan. Nowadays, we don't really need to show the contrast between candidates. They are about as far apart as one can be on the planet.

Alex Shephard: I think that that is a big part of it. Our age of hyper-partisanship, whatever you want to call it, makes them less necessary. To that extent, the debates, I think like much else on the cable news space, resembles a sporting event more than anything else. In both the debates in 2016 and 2020, the polling that's done right afterwards, everybody said, "Of course, Hillary Clinton won these debates. Of course, Joe Biden won these debates." They did certainly communicate ideas about Donald Trump's erratic temperament, fitness for office, you could say. They had no bearing themselves on the actual electoral outcome.

Brooke Gladstone: You had a take that I loved that definitely flies in the face of what appears to be the Republican position. You wrote that the current presidential debate format in which moderators are discouraged from interrupting even the wildest statements and in which an appearance of neutrality is privileged over any rigorous application of facts or for that matter, journalism, all of this heavily tilts the debate format as it stands toward Republicans.

Alex Shephard: Yes, this I think is a larger problem with this type of journalism, but you see it in debates in particular, which is that there's an unwillingness to show yourself as moderating more on one side than the other, even when that's a necessity. Now, I think this is one reason that Donald Trump let things go off the rails in the first presidential debate last year, is that it just took a long time for Chris Wallace to try to put the leash on. Now, if you're most concerned with appearing that you're neutral or above the fray, that you don't have a horse in the race, you have to stand back a little bit.

What we've seen, I think, increase, particularly in the last two presidential cycles, is the Republican candidate, in this case, Donald Trump taking that format and really benefiting from it. There's another issue as well there, which is that when you are forcing the candidates to fact-check each other, then you're in a situation in which the Democratic candidate is also having to spend most of their time fact-checking the Republican instead of saying whatever their response is to these issues. This is not to say that Democrats don't also constantly utter falsehoods or erroneous statements in debates, but that the share of these tends to be much larger on the right.

Brooke Gladstone: Could this political exercise be saved? What would help save it?

Alex Shephard: There are a few ways to do it. I think the biggest one is to take out the audience. The best debate in the last cycle was, I believe, it was the first debate after COVID hit. It was Vegas in March of 2020, the Democrats still had the debate. There was some social distancing, but part of that meant getting rid of the audience themselves. What you got was a much more interesting policy-focused debate. I think that changing the way that moderators are deployed is also one. I think the way that we've done it for a long time is to have very sober network news anchors.

As I've stated, those people often are unwilling to get in the mud when they have to. I do think that having experts talk to the candidates about policy issues themselves would make for a more substantive and interesting debate.

Brooke Gladstone: Experts meaning have economists come up there and put them through their paces?

Alex Shephard: Exactly. One issue in particular that I think is symbolic of the failure of presidential debates is the lack of coverage of climate change. Every climate change reporter I know obsesses over this every debate for good reason. This is arguably the most pressing issue from a global perspective of our time and yet it is never talked about. I think one of the reasons it's not talked about is partisan, that there's one party that cares much more about this issue than the other. I think there's also a discomfort with talking about it among journalists who don't have expertise in that field.

I think the biggest problem with the debates right now is just that they're a symptom. I think we want to see them as a cause of democratic failure. I think we want to go back to this theoretical time in which we cared more about substance than about the glitz of the presidential campaigns. One idea that comes up a lot is, "Oh, we'll just have the debates on a radio now because that'll make people focus more on the issues and less on the appearance of the candidates." Maybe I'm a cynic but I just think that the system as it is right now reflects a host of other failures.

That even if we were able to have a buttoned-up professorial presidential debate, it just would be a disaster because the political system itself isn't set up for that type of political conversation.

Brooke Gladstone: Your stance is that the RNC's possible withdrawal offers an opportunity to scrap the presidential debate altogether. This would be a good thing.

Alex Shephard: What we're losing is a contest that I think has grown increasingly shallow but also banal at the same time. We have these long, often interminable "debates" in which very little is actually accomplished. In theory, these debates should be another shining example of the American democratic tradition in which the candidates come together and spar and test their ideas. Instead, we have one that I think largely serves the interest of cable news.

It's soundbite driven. It's obsessed with minor gaffes that often distract us from larger issues within presidential campaigns. I think some people have pointed out, not incorrectly, losing the debates is another sign of the right's growing disinterest in democratic governance. It's not the most important sign of that by a long shot. I think even fixating too much on the presidential debates serves as a distraction from more important issues, particularly the assault on the right to vote that's happening. I think losing presidential debates, that's a bigger loss for cable news networks than it is for the American people.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you very much, Alex.

Alex Shephard: Thank you so much.

Brooke Gladstone: Alex Shephard is a staff writer at The New Republic. He recently wrote the article, Let the Presidential Debate Die. Thanks for listening to the midweek podcast. Big show hosts on Friday around dinner time. Check it out.

[00:16:00] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.