Trump Caught On Tape Talking About Classified Documents

( Department of Justice / Associated Press )

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media's midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. On Monday, there was breaking news in the classified documents case against former president Donald Trump.

News Anchor 1: Begin tonight with breaking news. We have obtained what is expected to be a central piece of the government's case against Donald Trump. The actual audio recording of the former president talking as if he's showing a highly classified document on US war plans against Iran, with people not clear to even know it exists, let alone what's in it.

Brooke Gladstone: The recording released to CNN by the special counsel working on the Department of Justice's indictment of Trump is reportedly of a 2021 meeting in Bedminster, New Jersey, where Trump discussed and seemingly showed secret documents to a group of onlookers.

[laughter]

Donald Trump: I just found-- isn't that amazing? This totally wins my case, you know. Except it is like highly confidential. Secret.

Brooke Gladstone: According to the indictment, four people were in the room with Trump at the time, and they didn't have the clearance to see the documents he was flaunting.

Donald Trump: See, as president, I could have declassified it. Now, I can't, but this is still a secret.

Trump Staffer: Now, we have a problem.

Donald Trump: Isn't that interesting?

Trump Staffer: Yes.

Donald Trump: It's so cool.

Brooke Gladstone: Trump has pleaded not guilty to the 37 charges that include willful retention of national defense information under the Espionage Act, obstruction of justice, and making false statements. Given the news of the leaked audio file, we decided to revisit an interview we recorded in January shortly after classified documents from both President Biden's and former Vice President Pence's tenures as VP were found where they oughtn't to be. The discovery of Biden's classified documents starting in November of last year invited some unsettling comparisons.

News Anchor 2: Two investigations, two presidents as President Biden and former President Donald Trump were being investigated for their handling of classified documents.

Brooke Gladstone: The FBI's raid of Trump's Mar-a-Lago home late last summer was the climax of a year-long news saga that started with a subpoena and led to the indictment brought against Trump earlier this month. The subpoena was the first of many efforts to recover Trump's errant documents. The Biden White House actually initiated the searches. What's more?

News Anchor 2: The White House points out the two cases are different, especially since Trump had more than 10 times the number of documents at Mar-a-Lago, and he refuses to fully cooperate.

Brooke Gladstone: According to the Department of Justice, more than 300 documents related to his time in office were found in Trump's home at Mar-a-Lago. What was in all those documents? 31 of them were categorized as highly sensitive information and were included in the indictment, each carrying a charge of willful retention of national defense information. As more folders are found at more houses, you got to wonder how much of this stuff is just lying around. Oona Hathaway is a professor at Yale Law School and former special counsel at the Pentagon. In her Pentagon role, she had the highest level of security clearance the government provides, and even the power to classify documents.

Brooke Gladstone: Last year, you wrote that the vast bulk of the classified information you saw was remarkable for how unremarkable it was. Can you give us a sense of scale?

Oona Hathaway: The problem is really out of control, frankly. The last year that we have data was in 2017, and then it was around 50 million classified documents were created that year. It means a lot of things are classified that shouldn't be classified.

Brooke Gladstone: That 2017 data say that about 4 million Americans with security clearances classified those 50 million documents at a cost of about $18 billion.

Oona Hathaway: We bring in all these outside people to manage this information. Of course, they have to have clearances of their own, but the more people who are touching this information, the more vulnerability this information really has. The irony of all of that is that the more that is classified, the less well-protected the information really is.

Brooke Gladstone: You have these three classifications: confidential, secret, and top secret. Then special compartmented information receives a special designation. This is the real deal. It has to do with human intelligence, satellite intelligence, and so forth.

Oona Hathaway: Yes, exactly. In addition to those three levels, there's a separate designation, which is sensitive compartmented information, SCI. That's classified information that often is derived from intelligence sources or methods, compartments of information that are set up so that if that compartment is compromised, other compartments aren't compromised, but also so that you can limit access to that compartment. These are very tightly guarded programs.

Brooke Gladstone: Weren't some of this level of classified documents found in Mar-a-Lago?

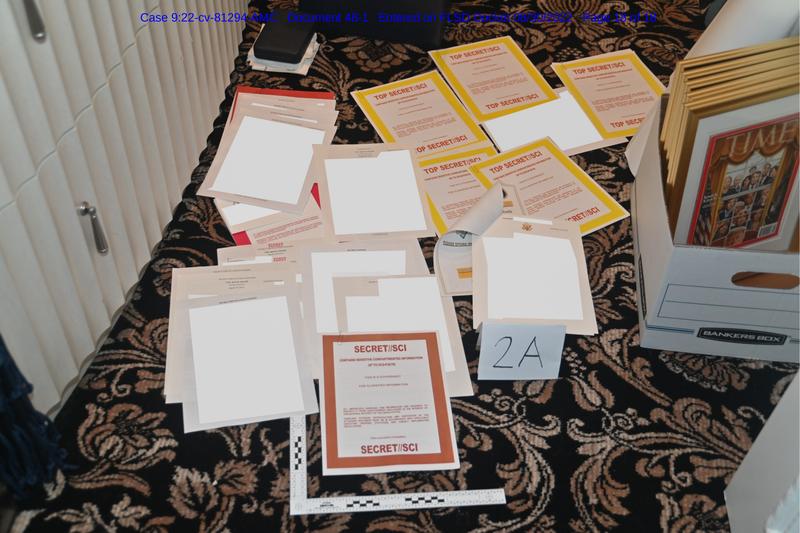

Oona Hathaway: Yes, they were. The information that we have is not very extensive, but we do have this photograph that was interestingly released as part of the investigation. From that, we can get some insight into what documents were there. We can see that very bright red letters in that photograph that shows, "TOP SECRET//SCI." That's supposed to be kept in a government facility where access is extraordinarily limited.

Brooke Gladstone: They have to be reviewed in a SCIF?

Oona Hathaway: Yes. The SCIF is a sensitive compartmented information facility. It's extremely well protected in terms of sound, in terms of access.

Brooke Gladstone: These designations are pretty obvious. They're stamped at the top of the document. You said that sometimes the cover pages are even a bright color so they can't be mixed up with other documents.

Oona Hathaway: Yes. The most sensitive documents, top secret/SCI documents have these bright cover pages on them, bright yellow, and red, that make it very clear that this is a document that is supposed to be handled in a sensitive way. They do that precisely to make it hard to make a mistake, so it doesn't get shuffled in with the other papers.

Brooke Gladstone: We don't know much about what classified documents were found at Joe Biden's house from his days as vice president. One of the reasons why we don't know is because the people who found them weren't cleared to look at them and had to pass on the whole job to someone else, right?

Oona Hathaway: As I understand it, and of course, this is just from public reports, his private attorneys were going through materials that he had taken with him after he left office as vice president and tripped across a classified document. The minute they saw a classified document, they stopped looking and they notified The National Archives, which notified the Department of Justice. Then, they had to send in people to investigate more fully who actually had access to those documents.

Brooke Gladstone: President Carter signed the Presidential Records Act, which set this whole urgent need to archive in motion in a real way back in '78. It didn't really apply to him, though. It didn't apply until Reagan came in. Yet, they found documents at Carter's house in Plains, Georgia.

Oona Hathaway: This is not unusual. It is part of the difficulty at the very highest levels of government. How do you separate what is part of your work as a government official and what is you as a private person? Sometimes, the lines between the two get pretty blurred. In the case of then-Vice President Biden and Vice President Pence, they would unlikely have been the people who box these documents up. What would've happened is at the end of the administration, their aides would've gone through and boxed up the documents and probably should have been responsible for making determinations about what are personal papers that really should go home with them, and what are documents that should be going to The National Archives.

Brooke Gladstone: Have you noticed any red flags in the media coverage of the Biden versus Trump classified documents events?

Oona Hathaway: I think early on everyone threw up their hands and said, "Oh, what Trump is being accused of, President Biden, when he was vice president did exactly the same thing. Why are they going after Trump?" Coverage has become a little bit more nuanced. There's a little bit more recognition, although still not widespread, that there is a difference between these two cases, because in one case, The National Archives was requesting over and over and over and over again access to information that they believed had been removed by the Trump administration and that needed to be returned to The National Archives. In the other case, it was President Biden's own personal attorneys who alerted The National Archives that there might be documents that were the property of the US government, and then they invited them in to scrub the house from top to bottom.

Brooke Gladstone: There's a lot of weirdness in the classification system. The CIA drone program was widely covered, and yet its very existence was top secret. What are the biggest risks of over-classification?

Oona Hathaway: Maybe the most dangerous one is that it makes it very hard for the government to disclose its activities to the American people. The Drone program was one of the most highly classified government secrets, even after it was very much an open secret. Everyone knew it was happening, but President Obama couldn't even talk about it until finally he decided the whole thing was absurd, declassify the existence of the program, and start talking about it.

That's absurdity that the American people can't even be told that the American government is running a significant program of using military force abroad through these remotely piloted vehicles. What are the consequences of that and where are they being used, and who's making the decision and who are we trying to kill with these drones and why are we doing this? How much does it cost? None of those questions can be talked about with the American people because those who know about it can't even disclose the facts of it, including members of Congress. They can't talk about it with their constituents, even when it's a program everybody knows about.

Brooke Gladstone: What about the potential for press intimidation? Reporters of the New York Times have gotten into trouble, a fair amount reporting classifying information, some of which could be argued is genuinely secret and some, like dropping bombs, is very hard to keep under wraps. What are the freedom of information implications? Laying aside the fact that some secrets ought to be kept.

Oona Hathaway: Yes. When they publish articles about these programs that could potentially put them at risk for prosecution under the Espionage Act. In fact, when Julian Assange, who is a controversial figure, but he was initially charged for hacking documents when he created the WikiLeaks webpage where you can get access to all these leaked documents. The Trump administration added a charge under the Espionage Act.

That made many journalists very nervous because what he was being charged for, making available to the public documents that he had received that had been leaked and putting them on the internet, was the exact same thing that a lot of mainstream news sites do. The only thing standing between them and prosecution is a history of the Department of Justice deciding not to prosecute these cases. That's where the Assange case makes everybody nervous because that suggests maybe the Department of Justice won't stick to that forever.

Brooke Gladstone: In the Assange documents were some materials related to sources and methods, as I understand it, that could possibly affect national security.

Oona Hathaway: I'm a big advocate of mass declassification and in fact, mandatory declassification of documents and materials that are more than 10 years old. The one exception to that is for information that applies to sources of methods and particularly human sources, human intelligence. What he did was reckless, but the decision to prosecute him under the Espionage Act makes a lot of much more mainstream journalists who would never put something online, who generally have the practice of notifying the government before they're going to place these documents online just in case there is some good reason that they shouldn't be disclosed, puts them at risk. I think that's the danger and the concern.

Brooke Gladstone: Ed Snowden, he is celebrated for exposing a data collection program so sweeping its swept Americans into its more, but some of those leaks did arguable harm to national security, right?

Oona Hathaway: Part of the challenge here is that the reason that those programs were kept from the American people for as long as they were, was because, of course, they were extraordinarily highly classified. Even when Congress knew about these things, if you're briefed on an intelligence program in a highly classified setting, you have a very hard time doing anything about it if you're a member of Congress because you can't tell your constituents about it, you probably can't even tell your staff about it. You may not even be able to tell your colleagues about it if they haven't been read into the program. Part of the reason I think these programs can persist is that those who learn about them can't do anything about it.

Brooke Gladstone: Please fact-check me. Didn't some of Ed Snowden's revelations put legitimate sources and methods at risk?

Oona Hathaway: That is what the government says. I actually can't even look because I'm not cleared into those programs.

Brooke Gladstone: You can't look at stuff that was leaked?

Oona Hathaway: If I ever want to get access classified information again, so be read into a classification program again, I can't look at improperly leaked material that's remains classified. Just because it's leaked doesn't mean it's declassified.

Brooke Gladstone: As somebody with a clearance, you are not allowed to look at it. I am allowed to look at it.

Oona Hathaway: There is absurdity about that because of course--

Brooke Gladstone: Yes.

Oona Hathaway: [chuckles] It's hard for people like me who are researchers.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much.

Oona Hathaway: Thank you so much for having me.

Brooke Gladstone: Oona Hathaway is a professor at Yale Law School

[music]

Thanks for listening to this week's midweek podcast. Tune into the big show on Friday evening where under the microscope, we put the newest variant of conspiracy theory candidate, by which I mean Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.