The “Too Old” President and Political Doppelgängers

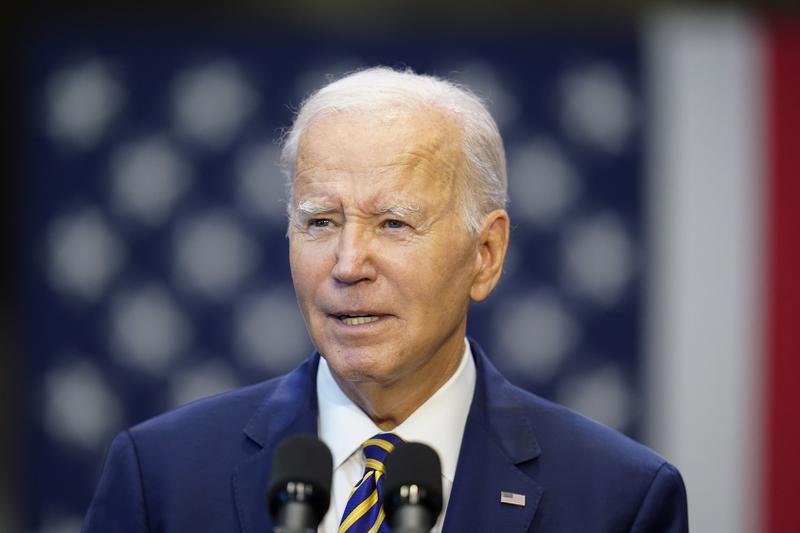

( Alex Brandon / AP Photo )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC studios.

Brooke Gladstone: This week, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy announced an impeachment inquiry into Joe Biden without any direct evidence of high crimes or misdemeanors.

Stephen Collinson: The Republicans in the House could seed a view that corruption is endemic. Oh, Biden's just the same as Trump, a curse on all their houses.

Brooke Gladstone: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Every presidential candidate is framed by opponents and the press. Is it useful or just lazy?

News clip: I can't walk five feet without somebody going, "Is Joe Biden too old to run for president?" It's all I hear all day.

Brooke Gladstone: Plus, writer Naomi Klein has long been confused with another Naomi. Now, a peddler of conspiracies, Klein followed her down the rabbit hole.

Naomi Klein: If doppelganger art is any guide, attempts to confront your doppelganger and be the last you standing rarely end well. It often ends with you stabbing yourself.

Brooke Gladstone: It's all coming up after this.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. This week, the House took action.

Kevin McCarthy: Today, I am directing our house committee to open a formal impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden.

Brooke Gladstone: They're accusing the president of profiting from his son Hunter Biden's four business deals. A CNN headline dubbed it the most predictable impeachment investigation in American history. CNN political reporter, Stephen Collinson wrote that "it felt more like an inevitable consequence of America's diseased politics than a constitutional thunderclap but if this is a sign of disease then the condition is spreading."

News clip: The governor of New Mexico is now facing growing backlash, including calls for impeachment, following her executive order banning concealed carry for self-defense. It followed the recent shooting deaths of three children in that area.

Brooke Gladstone: In Wisconsin.

News clip: State Republicans are threatening to impeach the newly elected state Supreme Court Judge, Janet Protasiewicz because she spoke the truth about their heavily gerrymandered electoral maps.

Brooke Gladstone: As to the Biden probe, House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer spent eight months digging into this case promising to produce a bombshell.

James Comer: We found that the President did have transactions that went to his family members while he was vice president. That was something that the media said never happened, and we proved that nine Biden family members were a part of the [unintelligible 00:02:42]

Brooke Gladstone: Less bombshell than pop gun, there's still no direct evidence tying Biden to any wrongdoing. On CNN, South Carolina rep, Nancy Mace said, no, but soon, maybe.

Kaitlan Collins: Isn't it supposed to be the evidence that leads you to pursue impeachment and impeachment inquiry?

Nancy Mace: Well, that's what the inquiry is for. It's to get more evidence.

Stephen Collinson: There is a perception of a conflict of interest.

Brooke Gladstone: That's CNN's Stephen Collinson, who gave us his take on what's fair and what's not.

Stephen Collinson: I think it is fair to ask why Hunter Biden was on the board of a Ukrainian energy company, for example, while his father was vice president and very involved in issues in Ukraine.

Brooke Gladstone: Stephen, isn't that standard issue nepotism? It's unsavory but no high crime or misdemeanor.

Stephen Collinson: Yes. The idea that this reaches at this point the level of an impeachable offense let alone investigation is a very hard case to make. Clearly, there is in every Congress, and particularly in the polarized times that we're in now, political motivation for almost every investigation.

Brooke Gladstone: McCarthy is very weak. The GOP only has a five-seat majority in the House and he's beholden to a rump crew of very far-right members for his job as speaker. He has to do what they want and they want to do what Trump wants.

Donald Trump: They have absolute proof that Biden is being paid off by China, Ukraine, and many other countries, and the press doesn't even write about it.

Brooke Gladstone: Obviously, there's no evidence of any payments from China into Joe Biden's bank account. It is Trump's desire to spread impeachment around, right?

Stephen Collinson: By moving towards potentially impeaching Biden, the Republicans in the House could seed a view that corruption is endemic, that the offenses of which Trump is accused, the four criminal trials, the looming next year, his own two impeachments are just par for the course. Oh, Biden's just the same as Trump, a curse on all their houses.

Brooke Gladstone: This impeachment fever that's happening in all sorts of red states, is that just simply catching the bug or a way to discount the gravity of an impeachment?

Stephen Collinson: It is seen as just another tool in the toolbox of hardline politicians. A lot of experts worried even during the Trump impeachment, the continuing resort to impeachment as almost a measure of censure because at that point, it was clear that Trump wouldn't be convicted in the Senate is denuding the gravity of impeachment and it could be something that we would see more and more often, and that seems being born out by events. Are we going to go forward and every president is going to be impeached when there's a house of the opposite party? Seems like it's quite possible.

Brooke Gladstone: Even though the Democrats knew they weren't going to win, they wanted this censure on the historical record.

Stephen Collinson: Yes. Having said that, I think we should make the distinction that there were clear actions that Trump took that led to his impeachment. At this point, there aren't clear actions that Biden took that appear to merit impeachment, and there's a difference in these two cases.

Brooke Gladstone: Critics of the media coverage around this case have pointed out a troubling trend, I think. Media critic Jay Rosen noted that it took the AP until the 14th paragraph in its piece to clarify that the GOP had no evidence to present and instead focused on the idea that the impeachment itself was historic. It took the New York Times until the seventh paragraph in its piece to make the same point about the evidence. The lack of evidence wasn't mentioned in the headlines and we've gotten used to saying without evidence when it comes to things that Trump says like the election was stolen, we always say without evidence. Isn't it fair to say the same about this impeachment trial? Especially if it continues to be Kabuki theater? What's the real story here?

Stephen Collinson: Of course. I think it was on the front page of The Times. They said something to the effect of McCarthy opens impeachment inquiry caving to the right, something to that effect. I can speak for myself, we have pointed out repeatedly that there's no direct evidence of the President being involved.

Brooke Gladstone: Would you put in a piece, at this point, it appears they're trying to impeach the president for the alleged transgressions of his son? Would you do that? I know there is a tremendous tendency, having analyzed the media now for more than 30 years myself, that this excruciating need to be fair enables certain obvious and useful context to be left out of the story.

Stephen Collinson: It's difficult for me to say that I would definitely write that because I think everything needs to be dealt with in context, but I think--

Brooke Gladstone: That is context. I'm not trying to put you horribly on the spot. Just a little bit on the spot.

Stephen Collinson: My job is to write analytical journalism and that may move a little bit to opinion.

Brooke Gladstone: If the evidence that they have provided entirely involves certain self-interested behaviors of Hunter Biden, alleged transgressions, and nothing points to the president, isn't it a simple fact that what they're presenting is a kind of by-association argument?

Stephen Collinson: They are trying to create a situation politically in which the behavior of the son is blurred in a way that suggests wrongdoing by the President. I think that's clearly a political tactic. I don't know what necessarily the terminology or the particular phraseology I would use but I don't have any problems saying that that appears to be exactly what they're doing and I think I've written that. They're trying to seize on the business activities of Hunter Biden to suggest a massive abuse of power by the president because they don't have evidence of a massive abuse of power by the president. That is a fact.

Brooke Gladstone: One last question. The White House in the Obama days certainly and also in the Biden Administration has often been criticized by Democrats for not defending itself vigorously enough. It seems this White House has made a decision to defend itself. What do you think?

Stephen Collinson: President Biden is not quite as eloquent as Obama. He doesn't do as many public appearances. I think I perhaps would argue the White House doesn't have a president that is as good as going out and driving the message. They do have a very aggressive fightback operation as you said, a war room that they're now starting to stand up against what they regard as completely frameless impeachment proceedings.

Honestly, I don't think there's great evidence that they're being that successful in fighting back against these allegations. I remember the Clinton administration, during that impeachment, were exceedingly aggressive in defending Bill Clinton, getting him out, going around the country. He was very active in fending off these allegations. In the end, it worked for him because he emerged from the impeachment process, and in the last period of his presence, he was much more popular than the people who tried to impeach him. I guess that's the model for the White House, but we're in a completely different media era right now.

Brooke Gladstone: And a completely different political one.

Stephen Collinson: Yes. If you look at some of the president's policies, the Recovery Act, an attempt to reignite manufacturing, for example, a lot of the things that Biden has done, which by any objective view of the presidencies of the last 20 years, they're pretty impressive legislative achievements. Some of these things take a long time to roll out and a lot of people aren't feeling the benefits for them, even if they're working for the economy.

You've got this situation whereby President Biden is almost running for reelection on the basis of a recovering economy, but a lot of people aren't appreciating that. I often think about the selling of the Iraq war, which as a political campaign was very successful but, of course, when you look back now, many people regard it as one of the greatest foreign policy disasters of the modern age. Sometimes administrations are good at selling things which perhaps they shouldn't be selling.

Brooke Gladstone: This impeachment, we don't need in the current political environment to sell it to everyone or even to most people. Basically, just people who vote in primaries.

Stephen Collinson: The political impact of impeachment may well be decided in those 20 or 30 districts Republicans won in 2022 where Biden won in 2020. If impeachment comes to be seen as just a naked political action, those Republicans could be hurt. In the same way, we've seen how Republican extremism has actually hurt the GOP in more moderate suburban districts in the 2020 election and the 2022 midterm election and in the fact that they didn't win back the Senate and they didn't get that huge red wave that they expected in the midterm elections.

In a way, I don't really like talking about the political implications of impeachment because the question should really be, is this a justified impeachment or not? I think we need to keep the focus on that because impeachment is such a grave thing. There will be political after-effects and it will be the job of the White House to try and exploit those political after-effects because clearly, it's very unlikely that Joe Biden is going to be convicted in the Senate trial so he'll be here at the end of it. The question is, what political impact does that have on him?

Brooke Gladstone: Stephen, thank you very much.

Stephen Collinson: Thanks

Brooke Gladstone: Stephen Collinson is CNN's senior political reporter.

Micah Loewinger: Coming up, two geriatric men or the likely presidential nominees. Is there such a thing as too old for the job?

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: And I'm Micah Loewinger. On Wednesday, Utah Senator Mitt Romney announced he will not seek reelection in 2024.

Senator Mitt Romney: At the end of another term, I'd be in my mid-80s. Frankly, it's time for a new generation of leaders.

Micah Loewinger: That parting shot was aimed at both of the likely front runners, though at 80 Biden is the oldest to ever occupy the Oval Office and the prospect of adding on another four years has set the discourse ablaze.

News clip: That's all I hear all day. I know it's all you here all day. I can't walk 5 feet without somebody going, "Is Joe Biden too old to run for president?"

Micah Loewinger: Some pundits say, "Yes," citing a growing list of warning signs like unsteady legs.

News clip: I just want to bring you some pictures that we've had in from the United States showing President Joe Biden who tripped and fell whilst handing out diplomas at a graduation ceremony.

News clip: President Biden trips, not once, not twice, but three times as he tries to climb the stairs to Air Force One today. He brushes off his pant leg and continues on.

Micah Loewinger: And verbal flubs.

President Joe Biden: There's no national treasure, none that is grander in the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon, one of the Earth's nine wonders, wonders of the world.

Micah Loewinger: Meanwhile, Biden's defenders say that age is just a number and that the gaffes are neither new nor inaccurate representation of his ability to run the country. Too old is just one shorthand signifier that contenders and reporters have used when framing candidate narratives in election years. John Kerry was designated a feet. George W. Bush, a frat boy. Trump, a carnival barker, just to name a few.

James Fallows is the writer of the Breaking the News newsletter on Substack and the former chief speechwriter for the Carter administration. I asked him whether this media trope whereby reporters reduce a candidate's essence to a single catchy trait is just a 21st-century phenomenon or if it goes back further than that.

James Fallows: If Abraham Lincoln were running for president right now, there'd be stories about is he too clinically depressed to bear the burdens of this office.

Micah Loewinger: That's what people wrote about him in his heyday.

James Fallows: Yes. The opposition press that day said, "Is he too closely related to chimpanzees to be president?" There was all this really horrific coverage of Lincoln, but anybody comes to that office falling short in some way. They are too old like Biden or they are too young like John F. Kennedy or Bill Clinton or Barack Obama. They are too much insiders like the first George Bush or they're too much outsiders like Jimmy Carter for whom I worked. Are they too much steeped in the culture of Washington like Lyndon Johnson or are they too little steeped in that culture and don't know how to get things done, again, like Jimmy Carter?

In Texas, Gerald Ford in 1976 ate a tamale with the entire wrapping on with the corn husk and that was part of his losing Texas. There is always a way that a president falls short. Interestingly, that comparison assumes some matching up against an immaculate perfect version of the person who would do everything right in office. Whereas the real choice is how does that person compare in the real history of that moment with the alternative?

Probably the starkest example was Franklin Roosevelt, too sick to run for office for reelection to his fourth term in 1944. Certainly, he was too sick. He died a few months later, but would the country or the world have been better off with Thomas Dewey instead? I say no. I think Franklin Roosevelt, too sick to run for reelection, still there was a reason they got more than 400 electoral votes that year.

Micah Loewinger: A lot of the coverage, while perhaps laying the articles about this topic on a bit thick, are quoting polls. For example, one that has been cited quite a bit from AP-NORC that found that 77% of people thought Biden was too old to serve another four years. This isn't just like in the chatter classes imagination. There is some real reflection of how voters are feeling.

James Fallows: Yes, but: First, those polls, a year plus before an election, they almost always show some limited enthusiasm for any of the choices because by definition, the two choices we end up with always fall short. There are flaws with any of the people who served up to us as alternatives.

The second is it's a very different question to ask, is Joe Biden too old for this job? Versus, is Joe Biden being too old a better or worse choice than Donald Trump who at the moment seems like the likely alternative? The third point I'd make is that any story whose starting point is how is factor X going to play with the voters really is a story that shouldn't be written because it's trying to tell voters what they're going to think and the voters will figure that out for themselves.

Micah Loewinger: I'm not getting the sense that you think it's off-limits to acknowledge Biden's age and journalists would be ignoring reality if they did. Can you give me some examples of the particular coverage, the kinds of specific articles you've seen that don't do it?

James Fallows: In one of the papers recently, it was noticed with raised eyebrows that Joe Biden in the midst of some huge trip to Vietnam said, "What time is it here?" As somebody who has made probably three dozen trips to that part of the world from the years we lived in Malaysia and Japan and China, I can tell you the most natural thing for anybody getting off a plane or begin a trip in that part of the world is what time is it here, and all the more so if you've been in India where the time zones are in the half hour.

Micah Loewinger: It's interesting to me that you didn't name The New York Times because I'm almost certain that they included the detail of his age in its headline about the coverage of that speech. You're too polite, James.

James Fallows: I'm Mr. Can't We All Get Along? I will say that The New York Times eight years ago and before that with Hillary Clinton led the coverage which has been rightly ridiculed as, but what about her emails, and so too, you can almost see an equation again, I would say led by The Times in Biden being old with Donald Trump being under dozens of felony indictments.

Micah Loewinger: I was actually reviewing a study published in the Columbia Journalism Review that found, "In just six days The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton's emails as they did about all the policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election." A disproportionate coverage about the emails compared to what matters most. I have seen a burst of Biden coverage this year from The Times, but do you think it's really that bad?

James Fallows: The election is still what, 14 months away [chuckles] so we haven't seen the full run of events. We haven't had anything yet comparable to the James Comey revelations 10 days before the final vote. I think it's worth being aware of this ahead of time. I think it's worth also asking this about the, is Biden too old coverage? It is a very legitimate topic and should be explored along with other things about Joe Biden's accomplishments and fitness for office and prospect.

If he were reelected to ask, what does it mean that he be by far the oldest person ever to hold this office? What do medical authorities think about the way he carries himself, the things he says, the things he does, et cetera? That's all legitimate. It is also legitimate and more important for the fate of the nation, asking what he has done in his now three-plus years in office.

Micah Loewinger: I'm 30 years old and I identify with the political frustrations shared by a lot of millennials, in part because I think many of us see our beliefs and our well-being not well-represented both materially and symbolically. I mean, you look at the average age of Congress, it's been trending upwards since the '80s. It's hard not to look at Dianne Feinstein, Mitch McConnell, Chuck Grassley, Biden, Trump. You see like a gerontocracy, right?

James Fallows: This is a genuine problem. Gerontocracy is a genuine problem. The Supreme Court is its own grotesque case of one. When the Constitution was written and life tenure was established for the Supreme Court, most people didn't live that long and you didn't have the idea that people would be on there for decades upon decades. The Supreme Court obviously needs to have 18-year limited terms. The Senate is different because there are elections, but I have written myself that Senator Feinstein should step down and we know all the complications of that to have held that office.

I speak having once been young myself, having worked in the White House when I was in my 20s. I remember celebrating Jimmy Carter's birthday on the campaign trail about a month before the election, and he had just turned 54. I thought, "God, that is so old." I think it's inevitable that the media would focus on the age of the oldest person ever to hold the office, but I think it is less useful to the public in considering our choices than the people putting out these stories might think.

Micah Loewinger: James, thank you very much

James Fallows: Micah, my pleasure.

Micah Loewinger: James Fallows is the writer of the Breaking the News newsletter on Substack, and the former chief speechwriter for the Carter administration. James Fallows thinks the press can and should ask questions about Joe Biden's age, but without letting it dominate coverage. When it comes to answers about his capacity to serve another four years, most of us don't have the expertise even to make an educated guess. Steven N. Austad, professor of biology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham does. He holds the university's Protective Life Endowed Chair in Healthy Aging Research. He's been reviewing footage of Biden and actuarial data, medical records released by his administration, and scientific literature about how the geriatric body and brain change. He says he hasn't seen proof that Biden is unfit for a second term.

Steven N. Austad: There's no indication that his age is affecting his performance. Now, if he had had some episodes that made us question his mental acuity, I think that would be different, but he hasn't had any episodes like some others have had.

Micah Loewinger: Okay, but he has been filmed falling and tripping multiple times over the last year and a half. Does that not count for anything?

Steven N. Austad: It does, but I think it counts in a different way than most people think. He tripped over a sandbag once. Think to note about that is he didn't hit his head, he didn't get injured. People fall all the time, but the older the people get, the more likely they are to be injured. For instance, Senator McConnell fell and got a concussion and all, but Biden was notable. He did not hit his head, he caught himself and he was relatively uninjured. I think if a 45-year-old senator had fallen, no one would've paid any attention to it. Somebody that's President's Biden age today is not like someone that age 20, 30, 40 years ago.

Micah Loewinger: Just because the science and healthcare for older people has improved?

Steven N. Austad: Exactly. One of the things that is interesting about this presidency is that you can go get his full medical report from this year online and it's very detailed. You can find out all the medications he's taking, and I do think that health transparency is important because we would want to know if he had some serious illness. We've had presidents in the past that had very serious illnesses that the public was kept from knowing about.

Micah Loewinger: I did look at the most recent report issued by the White House and his physician. I saw a lot of medications. I saw references to his stiffened gait and other ailments that I'm sure his doctors are watching very closely. I'm not studied in this, so I couldn't tell if this was just transparency theater, the White House trying to make it seem as if he's healthy. I know that when President Trump was in office and his administration issued updates about his health, it seemed selective. It didn't seem all that credible. In your professional opinion, are Biden's doctors telling us the full story?

Steven N. Austad: I thought it was very detailed and very honest. There were blood chemistry values, there was no glossing over his back problems that he has. It seemed to me like a very credible medical report. What caught my eye is that he's taking cholesterol-lowering medication, which is good. His cholesterol values, his blood pressure is excellent. To me, he's in remarkably good health for a man his age, which you would expect for someone that's had his health closely monitored for years.

Micah Loewinger: In an interview you did with New York Magazine, you acknowledged that Biden's speed and confidence in debates and really all his public speaking has deteriorated over time. The reporter you spoke with, Benjamin Hart specifically referenced the difference between Biden's 2012 debate against Paul Ryan-

Joe Biden: That's a bunch of malarkey.

Paul Ryan: Why is that so?

Joe Biden: Because not a single thing he said is accurate. First of all-

Paul Ryan: Be specific.

Joe Biden: I will be very specific

Micah Loewinger: -and his more recent speaking engagements.

Joe Biden: The best way to get something done if it holds near and dear to you that you are likely to be able to-- anyway.

Micah Loewinger: Is this type of aging, the kind that we as voters can easily pick up on? Is it indicative of his ability to lead, make important decisions?

Steven N. Austad: We do lose processing speed as we get older, the speed with which our brain processes information, but that's not really a critical component of the thing that I think presidents should be doing. They should not make staff decisions and they often don't have to. What they do is they listen to a lot of advisors and synthesize what they hear and come up with measured decisions. The changes that we've seen in Biden over the last decade don't seem to me to have anything to do with his ability to do exactly that.

One of the things that you have to consider is that aging makes people different. To a first approximation, all 25 and 30-year-olds are the same from a health perspective. That's not true when you get older. There are 80-year-olds that are running marathons and there are 80-year-olds that can't get out of a chair unassisted, and that's the same for mental properties. I think the best indication of someone's decision-making ability is the recent decisions that they've made and we're not privy to a lot of the decisions that the president makes. I don't see any obvious changes in that property over the last terms he served. If you look at Biden's history, I mean, he grew up with a terrible stutter. He's always misspoke at times.

Micah Loewinger: A recent study conducted by the Rand Corporation, which was partially funded by the Pentagon found that as the average age of our politicians continues to increase, dementia is a "emerging security blind spot" for the federal government. Looking at Mitch McConnell, Dianne Feinstein, other high-ranking officials that maybe aren't even in the public eye as much, how severe of a risk does our aging leadership and dementia in particular pose to our country?

Steven N. Austad: Politicians are getting older, that the world is getting older. We're living longer than we ever have in the 300,000-year history of our species right now. We are going to have more and more politicians and more and more people exhibiting dementia because it doubles in probability every five to six years. This goes back to my point about the transparency of medical records. I think that ought to be mandatory for anybody in a national office.

Micah Loewinger: Does the science in your opinions suggest to us that our government would be safer and more effective if we capped the age at which politicians can serve.

Steven N. Austad: I don't believe that there should be. There are some people that are idiots at 40 and they should not be serving. 2,500 years ago in ancient Sparta, you had to be 60 years old to be on a governing council. 60-year-olds, 2,500 years ago was a very different 60-year-old than today. One of the early researchers in aging actually said that voting rights ought to be taken away from people after the age of 50 because they no longer were sensible.

Micah Loewinger: You're talking about Raymond Pearl in the 1920s.

Steven N. Austad: Also, Noah Webster of dictionary fame thought that no one should be able to hold public office until they were at least 50 years of age. There's dramatic historical differences of opinion.

Micah Loewinger: You seem confident that Biden has what it takes to remain healthy enough to serve another four years and be a competent leader. That said, are there signs we should be looking for to determine a more substantial decline that would make him unfit for office?

Steven N. Austad: I think as a window into someone's health and mental competence, the stress and strain of a presidential campaign is likely to be very revealing. If he melts down repeatedly during the presidential campaign, then I would say that's something to be concerned about. That's also the case of his opponent, whoever that might be.

Micah Loewinger: The way his public appearances are already selectively edited and mined by some in the news media, and I'm thinking of Fox News in particular. We would be led to believe that every time he speaks, he's verbally wandering and having to be yanked off the stage or protected by his staff. It seems like the reason we're even speaking about this topic at all is that Biden has lost his gift of gab if he ever had it.

Steven N. Austad: That's the thing. I think he's always had these speech lapses, but they've never turned into reasoning lapses that I know about. This is something that has been with him his entire career. People used to make jokes about how often he misspoke and anything that he says will be magnified because of his age, but I don't think that's really indicative unless it becomes a lot more of an issue than it currently is. Unless he can't keep his thoughts straight on a debate stage, for instance.

Micah Loewinger: Steven, thank you very much.

Steven N. Austad: It's been a pleasure talking to you.

Micah Loewinger: Dr. Steven N. Austad is the Protective Life Endowed Chair in Healthy Aging Research at The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, what do you do when you have a doppelganger making mischief in the world? You learn from it.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. The writer and activist, Naomi Klein has been confused for writer Naomi Wolf for much of her career. Wolf rose to prominence with the book The Beauty Myth in the '90s, establishing herself as a bestselling feminist. Whereas Klein wrote acclaimed critiques of capitalism such as No Logo and The Shock Doctrine. To say Klein was often mistaken for Wolf is rather an understatement.

In the interview she did just before ours, the TV host mistakenly called her Wolf. The confusion has been incessant on social media. She even overheard people confusing her for Wolf and decrying her from a stall in a public bathroom. In fact, it was so unrelenting that someone tweeted a rhyme that itself became something of a meme. "If the Naomi be Klein, you're doing fine, if the Naomi be Wolf, oh buddy, oof."

The poem resurfaced when Wolf became ever evermore visible as a peddler of COVID conspiracies, suggesting the vaccinated people shed particles that impaired fertility and that masked children were spookily placid like Stepford wives in the horror story, and that proposed vaccine passports were akin to slavery. Ultimately, Klein decided to plunge down the rabbit hole to follow Wolf and emerged with a new book called Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. It's a wide-ranging exploration of doubling in our lives, culture, and politics. One of the first mysteries Klein set out to solve was how her doppelganger crossed over into the realm of conspiracy.

Naomi Klein: She had had this really humiliating experience with a publication of her 2019 book, Outrages. A interviewer confronted her with every writer's worst nightmare, which was that the book that she was there promoting had misunderstood some key historical facts and it meant that a really big part of her thesis was wrong. This was unveiled live on the air. It was extremely humiliating. I should know because a lot of people thought it was me.

Brooke Gladstone: Her publisher dropped her and the book was pulped.

Naomi Klein: She entered the pandemic in a very destabilized place and started getting a lot of traction with various kinds of COVID misinformation. At one point she was on Steve Bannon's podcast every single day for two weeks. She published a book with Steve Bannon filled with vaccine misinformation. They actually put out t-shirts together at one point. It's not like she's an incidental small minor figure in this world. She's really become a star getting everything she lost and more.

Brooke Gladstone: What Bannon gets from it is something more consequential.

Naomi Klein: He hopes to get an election victory out of it. I think he was the key strategist behind the idea that Trump could attract disaffected Democratic voters who had really felt betrayed, particularly over the issue of free trade agreements, where they had voted for Democrats multiple times, who promised that they were going to renegotiate these trade deals and not sign new ones and then didn't do it.

He brought a segment of the Democratic base over to the Maga. He calls it Maga Plus. The old red hat brigade plus all that my doppelganger has come to represent in terms of disaffected white COVID moms who were angry about lockdowns and masks and vaccine mandates for their kids, mixing in matching it with transphobia, xenophobia.

Brooke Gladstone: He's also really skilled at appropriating language. He's borrowed a lot from the Left.

Naomi Klein: He was building what I call the mirror world. Bannon makes the argument that because his listeners and he himself have been de-platformed on so many social media sites, they need to create their own parallel information ecosystem. If you get kicked off Twitter, you have GETTR. If you get kicked off YouTube, you have Rumble. If you can't do a GoFundMe, then you can go to GiveSendGo.

There's all of these direct mirrors and then he says, "We will never other you." That's what they do. Othering, of course, is a really key term in anti-fascist discourse because that's what fascists do. They create an in-group of belonging and then they designate other people less than human. They are othered, and that becomes a rationale for ghettoization for discrimination, and if it goes far enough extermination.

This whole mirror world is really an appropriation machine. You'll have key slogans from social justice movements like, I Can't Breathe from Black Lives Matter, suddenly being used by the anti-mask brigades holding up signs saying, "I can't breathe," about the masks or, "My body, my choice," about vaccines. What's extraordinary is that often the same people who are appropriating the slogan, my body, my choice or I can't breathe, support politicians who are banning abortion. It's really a one-two appropriation and attack of the original.

Brooke Gladstone: Back to Bannon though, you mentioned that he said he would never other those who would be canceled by the Left. You hold the Left responsible for a lot of its own ills. Things that they could have avoided easily and deprived Bannon of ammunition of this sort.

Naomi Klein It isn't only about the Left, I want to be really clear about this. I think that centrist liberals also have a lot to be introspective about. Bannon's an interesting mimic, but he also says, "Okay, what are you doing wrong that I can make a point of doing right." I don't think it's a great secret that Left movements though we talk a good game about standing for a culture of care, don't always treat each other in ways that are very caring. I think that has a lot to do with the social media platforms on which we communicate, where we perform doppelganger versions of ourselves.

Brooke Gladstone: In the course of your research, you began to see doubles everywhere and you describe how our politics have become doppelgangers as well. They're each other in a fun house mirror.

Naomi Klein: We became very reactive, very whatever they are, we are not. The classic example of this is the lab leak theory early on that was seen as a conspiratorial take on the origins of the COVID virus rather than something that was worthy of exploration. In recent months, we've seen some serious investigations of the lab leak theory, which deserved real journalism. I think we mistakenly sometimes think our job is just to do the opposite of what they're doing. If there's a huge amount of misinformation going on about vaccines, then we are going to be the people telling people to roll up their sleeves and get vaccinated.

That's okay, but not if it's at the expense of engaged debate about what else we might do. We could have had more focus on lifting the patents on those vaccines. It's one thing to say, "Oh, Bannon is generating a distraction machine with all of these wild theories that he can't get enough of." I think that is happening, but so is seeing the Barbie movie for the sixth time. There are different ways to numb and distract yourself, and I don't think that Steve Bannon has a monopoly on it.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's stop for a moment and talk about the title of your book, Doppelganger. It's History and it's meaning.

Naomi Klein: It's been in use since the 1700s. It comes from two German words. A doppel means double ganger means goer or walker. Sometimes it's translated as a double walker, but doppelgangers are also now a real favorite on the streaming platforms. They're through lines in the history of literature, Dostoyevsky, Edgar Poe, Oscar Wilde, Octavia Butler, Ursula Le Guin. I mean novelists love a doppelganger.

Brooke Gladstone: Star Trek. You have Lore and Data.

Naomi Klein: The multiverse. I think artists are drawn to the multiplicities of the self because we do live in a culture that encourages us to perfect the self. We have this illusion that we can do it, but we also know that the self can be undone in an instant by a terrible accident, by a psychotic break, by a bad trip, by a bad tweet.

Brooke Gladstone: By a BBC correspondent cutting the rug out from under your latest book.

Naomi Klein: I think that's true, and I think writers are particularly aware of it.

Brooke Gladstone: At first glance, your book could seem to be a bold act of personal branding to put the confusion between you and Naomi Wolf to bed at last. But you wrote that there's something humiliating about confronting a bad replica of yourself and something utterly harrowing about confronting a good one.

Naomi Klein: If doppelganger art, particularly film is any guide attempts to confront your doppelganger and be the last you standing [chuckles] rarely ends well. it often ends with you stabbing yourself. Like in Oscar Wilde's, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, where he stabs the portrait of himself growing old and ends up dying on the floor. One has to be very careful about trying to win a war with your doppelganger. I don't think I can do that. If anything, probably Brooke, I have inexorably [laughs] cemented the association for those who were not confused. Terrible branding. I do pride myself on being a really bad brand.

Brooke Gladstone: [laughs] Well, you got a history with branding.

Naomi Klein: This is actually the main reason I wanted to write the book. When I was in my 20s, I wrote a book called No Logo about the rise of lifestyle branding. We started to see the first branded humans, super brands as Michael Jordan's agent described him, but when I wrote that book, the idea that non-celebrities could also be brands was an absurd concept that was being pedaled by various management consultants. The game changer as we all now know, was social media, where suddenly it was very affordable to create a product version of us. That's what we're doing when we log onto one of these new platforms, decide the perfect picture that we want, and we write our little sassy bio.

I think we've barely begun to grapple with what it means to perform a product version of oneself because this thing I'm putting out here is a thing. A brand is not human. I think that partly accounts for the kind of public shaming that Wolf herself experienced and that so many other people have experienced because if you perform as a thing, people might believe you and start throwing hard objects at you and think that you will not bleed.

Brooke Gladstone: About the exercise of branding you observed and I really love this, that for it to be effective, it has to be simple and static, but people change, which can be disastrous for a brand. Also, we are not just one thing. We contain multitudes. You asked, "What aren't we building when we're building our brands?"

Naomi Klein: I think that that line is the most important line in the book to me, as life becomes more insecure, more precarious, we are encouraged to turn towards the self, which is something that the late Barbara Erin Wright discussed in the context of wellness and fitness culture. That this is a way of channeling our insecurities about the job market, authoritarianism, climate change.

We have plenty to worry about. These are crises that we are only going to confront together. That's why it matters that if the labor of the self, whether it's building the brand, perfecting the body, fortressing the family, we are only alive on this planet for a finite number of hours. If we are spending a huge number of them in this rat race of self-perfection, we're not going to be reaching toward each other building the collective power that I think actually stands a chance of getting us on a much safer, more stable path.

Brooke Gladstone: You quote Daisy Hildyard talking about the unseen world that we live in that we don't see. Could you read from Daisy Hildyard's Shadow Land?

Naomi Klein: "You are stuck in your body right here, but in a technical way you could be said to be in India and Iraq. You are in the sky causing storms and you are in the sea hurting whales towards the beach. You probably don't feel your body in those places. It is as if you have two distinct bodies. You have an individual body in which you exist, eat, sleep, and go about your day-to-day life. You also have a second body, which has an impact on foreign countries and on whales. A body that is not so solid as the other one, but much larger."

What she's saying is that we're implicated [chuckles] in these systems. We want to believe that it is just the bad them, but this is our world, this is our system. If we are fortunate enough to be in wealthier parts of wealthier countries, fortunate enough during COVID to be part of the lockdown class, we knew our comforts were only because of other people's risks and frankly other people's exploitation. We were reminded many times that people who were described as essential workers were really in many cases sacrificial workers. I don't think it's a coincidence that it's that moment when conspiracy culture just goes supernova.

I don't think it is just about the technology. I think it's about what we can't bear to look at, but part of the reason why we look away is because we are so conditioned to see ourselves first as individual consumers that we forget that we actually have the ability to join with other humans and build collective power. This is what we're not building when we're building our brands. That kind of collective power that would make it bearable to really look at our implications in these systems so that we can make our systems more just

Brooke Gladstone: In literature and mythology, the protagonist often must confront their doppelganger or be replaced, but your journey doesn't end with a confrontation with Naomi Wolf. She wouldn't meet with you. Instead, you said you found it more useful to think of this whole experience as an exercise unselfing. What does that mean?

Naomi Klein: It allowed me to be more playful and experimental as a writer because I figured that if countless numbers of people thought I was someone else entirely, I didn't have much to lose. [chuckles] I may as well just try. Unselfing is a beautiful term from Iris Murdoch, the British philosopher novelist, a state that she reaches for. It's not a state that you can be in all the time, nor should you be. It's the state that artists talk about when they're in a flow state where they kind of forget themselves and they're all flow or Murdoch is talking about how one feels when one is awestruck by beauty, so transcended by it that we forget ourselves. We are unselfed.

Brooke Gladstone: You also recommend unselfing to your readers as a way to break out of our doppelganger politics, but how does unselfing work for people who aren't following their doppelgangers down rabbit holes?

Naomi Klein: I have a very specific niche version of this with my Naomi Naomi confusion, but I think we all create doubles of ourselves. We do it when we create our brands. We do it when we try to perfect our bodies. We do it when we try to perfect our kids and turn them into little mini-mes. These are all examples of the self taking up too much space and kind of blotting out the sun. I really do think it's getting in the way of our ability to reach towards each other and do the kind of work that is our only hope of meeting our unbearable moment in history when so much is unraveling. We really need to do it.

Brooke Gladstone: Naomi, thank you so much.

Naomi Klein: Thank you so much, Brooke. It was such a pleasure.

Brooke Gladstone: Naomi Klein is the author of Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World. On the Media is produced by Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candace Wang, and Suzanne Gaber. With help from Shaan Merchant. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Andrew Nerviano. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone, and thanks to OTM correspondent Michael Loewinger for co-hosting this week.

Michael Loewinger: Thanks, Brooke. My pleasure.

[music]

[00:50:42] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.