The Whistleblower Who Changed History

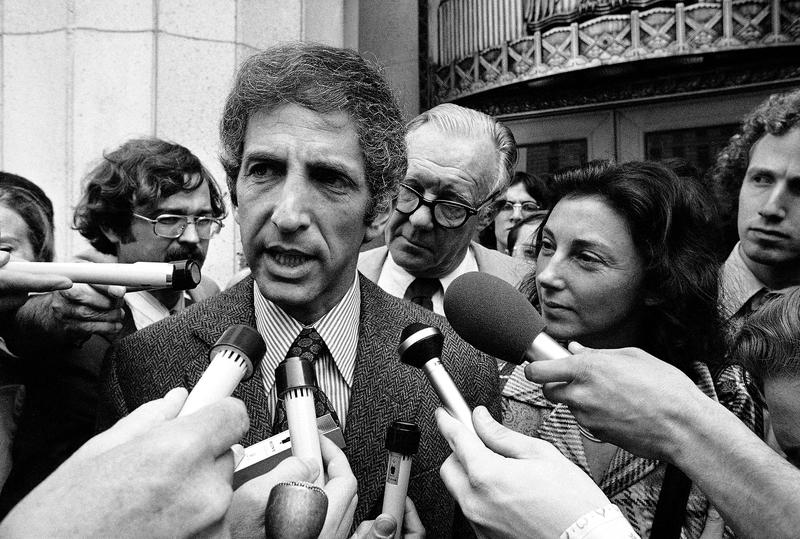

( Wally Fong / AP Images )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On this week's On the Media, the legacy of Daniel Ellsberg and the other truth-tellers of the Vietnam War era.

Daniel Ellsberg: I've enjoyed reading the papers the last week. I've been reading the truth about the war in the public press, and it's like breathing clean air.

Matthew Reese: McNamara wanted academics to have the chance to examine what had happened. He would say to us, "Let the chips fall where they may." I think guilt was a bigger motive and encouraged--

Les Gelb: The notion that this was a definitive history, is just plain wrong, because we didn't have that kind of access, and we never were allowed to do any interviews.

Laura Palmer: It was 3:00 in the morning, the phone rang, I picked it up. He said, "I got a job offer. Vietnam, six months, do you want to go?" I said, "Sure." Haven't you ever done dumb things for love? Come on, Brooke, tell us.

Speaker: My father had a favorite line from the Bible, which I used to hear a big deal when I was a kid, the truth shall make you free.

Brooke Gladstone: What we learned, what we haven't. It's all coming up after this.

From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Daniel Ellsberg died, as we posted last week show. Even though much has already been said, we need to say a little more because Dan has surely been vital to the On the Media project. Really any project charged with scrutinizing stories told about the world and distilling the truth from a churning around a burning funk, Dan Ellsberg knew when to lean in, and when to leave things behind. As a kid, he was gifted at the piano. That's him playing in this recent cell phone recording kindly sent to us by his son, Robert. Not bad, but some 75 years ago, he practiced many hours every day, until 1946, when he was 15. A car crash killed his sister and mother, and he left the piano, his mother's dream, behind.

A long time later, after years spent in Vietnam in the Defense Department and at the RAND Corporation, he left behind the career as a cold warrior he built at the seat of power and nearly gave up his freedom altogether because of the war. "No one is ever going to tell me again," he said, "that I have a duty to lie."

Daniel Ellsberg: I found myself handing out leaflets in this long vigil line. At first, I simply felt ridiculous. I knew that if any of my colleagues had ran to the Pentagon, or somehow to catch word of my doing this, they would think I had gotten mad.

Brooke Gladstone: If you'd ever met Dan, you were bound to like him very much, because he was zesty, contagiously curious, and so very gracious, even in disagreement, and he had a generous spirit. Once when he happened to be in our office, he performed some magic tricks for our avid star-struck staff, but to understand why all this matters, we need to offer a brief recap when he became America's Most Wanted as perpetrator of the greatest press leak in America ever.

The secret 7,000-page history of US involvement in Vietnam, going back decades, revealed Presidents of both parties and officials lying to the public and lying to each other. One of those officials was Daniel Ellsberg, and he wanted that history out.

Daniel Ellsberg: I'd been trying to get them out through congressional hearings, and was promised several times by various senators or congressmen that they would move it ahead, but each time they backed off for fear of the retaliation by the executive branch. Finally, I decided the only way to do it was to go directly to the newspapers.

Brooke Gladstone: TV followed in the pusillanimous footsteps of Congress.

Daniel Ellsberg: The TV stations, The NBC, ABC, CBS. CBS took the longest to decide no, the others were quite quick. They took a couple of days, actually, to decide that they didn't want to fight on this one. That's why I gave the interview to Cronkite, by the way, I felt that they'd behaved more respectively in that respect than the other networks.

Brooke Gladstone: Here's Dan in that 50-year-old interview.

Daniel Ellsberg: I've enjoyed reading the papers the last week. I've been reading the truth about the war in the public press, and it's like breathing clean air.

I remember very well the circumstances of that.

Brooke Gladstone: I spoke to Ellsberg on the 30th anniversary of all this in the summer of 2001.

Daniel Ellsberg: That was in a private home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I can see that now. The FBI was searching all over the country, to some extent, the world, for me at that time. They said it was the biggest FBI manhunt since the Lindbergh kidnapping. When I made that interview with Walter Cronkite.

Brooke Gladstone: Then, Nixon's infamous Plumber Burglarize Ellsberg psychiatrist office, a caper that led in a straight line to Watergate, pursued as a spy he finally surrendered to the FBI, but then the Nixon White House went too far dangling the plum post of FBI chief before the presiding Judge.

Judge: Mistrial.

Daniel Ellsberg: The judge ruled that the government had so tainted its own case as to make a fair trial impossible.

Brooke Gladstone: Ellsberg and his co-defendant, Tony Russo, facing decades behind bars were freed. Meanwhile, the newspapers who published parts of the Pentagon Papers faced legal penalties too, but New York Times journalist, Niels Sheehan, who first took on the leak, set the standard for clarity and courage. "This was about history," he said, "not ongoing operations." The High Court agreed and lifted the injunctions against publication. Justice Hugo Black wrote that, "In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam War, the newspapers did precisely that which the founders hoped and trusted they would do."

Richard Nixon: Son of a bitch thief is made a national hero and is gonna get off on a mistrial.

Brooke Gladstone: Richard Nixon.

Richard Nixon: The New York Times gets a Pulitzer prize for stealing documents. They’re trying to get at us with thieves! What in the name of God have we come to.

Brooke Gladstone: How would you gauge the courage of the press, pre-Pentagon Papers, and post-Pentagon Papers?

Daniel Ellsberg: Well, courage is contagious. 19 papers faced prosecution one after the other. As one injunction went out, another one took up that flag and carried it forward. That was courage. They were helped by the fact that The Times had, and the Post had unusual courage and being the first to do that. Having once had that experience, I think a generation of journalists grew up with a good deal of pride and saying, "We did our job. We have the guts to do this, and we can do it again." That was a very good precedent.

Brooke Gladstone: What about the impact of the papers on government officials?

Daniel Ellsberg: Well, I think nothing you can do can keep men in office from trying to hide their mistakes, their bad predictions, their crimes. When I say that, it's not from inside knowledge at currently, it's from my experience in the government when I was surrounded by intelligent, conscientious patriotic people who knew from month to month and year to year that their government, Republican or Democrat, was deceiving the public terribly about the information that had and the expert opinions he was getting. Those people, I among them, kept their mouth shut far too long.

Brooke Gladstone: In current whistleblower news, we just passed the 10th anniversary of Edward Snowden's leak about government surveillance. He says, from Moscow, that he has no regrets. This week, Democratic Senators Ron Wyden and Richard Durbin, together with Republican Senator Mike Lee, reintroduced the federal shield law that would, "Ensure reporters cannot be compelled by the government to disclose their confidential sources, and also protects their data held by third parties like phone and internet companies from being secretly seized." The idea is anathema to Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, who has offered the Pentagon Papers as Exhibit A in his opposition. He says such laws grant journalists privileges to disclose sensitive information that no other citizen enjoys. That's not true. Not just professionals who get paid to report the news would be protected, but anyone who commits an act of journalism and every citizen benefits.

Ellsberg, a true patriot, devoted the rest of his life to encouraging and supporting whistleblowers, and wondering where they all are. Tom Devine is the head of the Government Accountability Project, and he knows where they are. He says that Dan made the lives of potential truth-tellers easier by catalyzing a kind of cultural revolution.

Tom Devine: When I first came to the Government Accountability Project, the US was the only country in the world with a whistleblower law. We passed it in 1978. The second one wasn't until 1998, in Great Britain. Now there's 64 nations globally that have whistleblower laws. The United Nations has whistleblower protection, the World Bank has whistleblower protection, but it wouldn't have happened if there weren't a cultural revolution first. That cultural revolution created the political base to have the legal revolution that allows people to be lawful whistleblowers because now they have some rights.

Brooke Gladstone: When journalists report information that the public doesn't want to hear, they're routinely called traitors, especially in this profoundly fractured cultural environment. Do you have any proof that whistleblowers have a better rep than they used to have?

Tom Devine: In 2006, there was a survey of swing voters after the voters switched Congress from being all Republican to all Democrat. The question was, what is your priorities for this new congress?

83%, number one, said, "Reduce illegal government spending," which was predictable. Number two, ahead of ending the Iraq War, National Health Insurance, lowering taxes, the stronger rights for government whistleblowers. For the recent congressional elections, Marist poll found that 86% of probable voters wanted to have stronger rights for whistleblowers. Freedom of speech to expose abusers of power has won the Cultural Revolution.

Brooke Gladstone: You said it wasn't surprising to you that Ellsberg turned on the institution he really believed in. You said it's not unusual.

Tom Devine: It's not unusual at all for people to become disillusioned. What made Mr. Ellsberg stand out is he didn't just become cynical, he acted on the truth. In that sense, he was a real pioneer. Most folks would just shake their heads and say, "What are you going to do? I'm not taking any risk." He was wanting to risk everything when he learned the truth. It took him years of agonizing. That's very common in my experience.

Brooke Gladstone: You say it creates a very intimate crisis?

Tom Devine: Most whistleblowers that I've worked with, they've been in an organization for 20 to 40 years. That organization is their personal identity. It's their mission and their calling in life, and they believed in it. Then they stumble onto something and it's absolutely a life's crossroads. When someone comes into Government Accountability Project, and they haven't blown the whistle yet, my first duty is to try and talk them out of it. First of all, they have a right to make a fully informed decision that they're going to be professionally destroyed. Friends are going to abandon them. They need to know what they're getting into. They need to discuss it with their families that's depending on them, and so I need to warn them.

The second reason is because they have to make a firm commitment to finish what they started, because if they quit in the middle, the abuse of power they were challenging will be stronger and the aftermath of defeating them, and they won't have accomplished anything.

Brooke Gladstone: Ellsberg was always surprised that there weren't more whistleblowers.

Tom Devine: It doesn't surprise me. Mr. Ellsberg had extraordinary courage, and it took him years. We nickname whistleblowing, the sounded professional suicide. It means that a professional life that might have been very comfortable and successful is going to be a nightmare that you can't wake up from.

Brooke Gladstone: He did something that maybe no one had ever done before, but it was declared a mistrial, and he was let off the hook. Not really on the substance, it was the newspapers' trials that were finally decided on substance.

Tom Devine: His fate was the exception, rather than the role. Numerous whistleblowers are criminally prosecuted. On the corporate side, they're prosecuted for stealing the company property, the evidence of fraud against their government. On the civil service level, they're prosecuted for disclosing confidential information that's not classified. They're prosecuted for not being loyal to the government. They're prosecuted for conflict of interest. When you blow the whistle, the first thing that'll happen is a retaliatory investigation to find any dirt possible on you. That means there's going to be a poison cloud hanging over your head. Your life will never be the same.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet whistleblowers, over the past few decades, have changed the course of history more than any other time, you say, and that Ellsberg was the catalyst. Can you give me a few examples of whistleblowers we likely wouldn't have had without him?

Tom Devine: In the Iraq war, the marine science advisor, Franz Gayl, he was requested, semi-ordered, by the Chief Field General in Iraq to free up vehicles that would actually protect the troops against landmines. They're called MRAPs. They were using Humvees that weren't even designed to protect them against landmines. 90% of our fatalities and 60% of our casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan were from landmines. Thanks to his whistleblowing, the MRAPs were delivered. The casualties went down to 5% from landmines.

Nuclear power plants, and there was a story on Netflix about three nuclear engineers who stopped the three-mile island clean up from turning into a complete knockdown that would have taken out Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, Baltimore and Washington DC. They exposed that instead of losing track of 10,000 gallons of radioactive waste, it was 4 billion gallons of radioactive waste at our nuclear waste stuck, which forced a big upgrade in the cleanup.

Human rights abusers. Until not that long ago, people were coming in from foreign countries. The US government would stop them, accuse them of drug smuggling, without any evidence. Usually it was attractive women, usually it was near the end of a shift so they could get overtime. If they didn't find any drugs on the travelers, they would do body cavity searches. If that didn't work, they would take them to a hospital and do up to four days of laboratory tests, during which time those people couldn't contact their lawyers, their family, and thanks to a courageous customs inspector, Cathy Harris, that blew the whistle on this, that was changed from four days to two hours.

I could keep going on and on, but these people make a difference. The truth matters. They've been changing the course of history ever since they got rights under the Whistleblower Protection Act that can be traced back to Dan Ellsberg.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much, Tom.

Tom Devine: Thanks for having me.

Brooke Gladstone: Tom Devine leads the Government Accountability Project.

Coming up, a man in charge of compiling the Pentagon Papers would like to correct the record. This is On The Media.

This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. James Spader played Ellsberg in the 2003 film, The Pentagon Papers.

Pentagon Papers Clip: Tony Russo's girlfriend, Linda, let me use the Xerox machine at her advertising agency in West Hollywood. I'd copy from 1:00 to 4:00 in the morning, sleep for an hour or two, and have them back in the safe before anyone knew they were missing.

Brooke Gladstone: As we know, Ellsberg finally got the New York Times to take on those Xeroxed pages, but in the summer of '71, the paper was hit with an injunction barring it from printing any more scoops from the Pentagon Papers. With The Times put on ice, The Washington Post stepped in, got copies from Ellsberg, and went hunting for their own scoops. Steven Spielberg's 2018 film, The Post, tells that story.

The Post Clip: How am I supposed to come through 4,000 pages?

The Post Clip: They're not even loosely organized.

The Post Clip: The Times had three months. There's no way we can possibly--

The Post Clip: He's right. We got less than 8 hours.

The Post Clip: -- then we'd have 10.

The Post Clip: For the last six years, we've been playing catch up, and now thanks to the President of the United States, who by the way has taken all over the First Amendment, we have the goods. We don't have any competition. There's dozens of stories in here, The Times has barely scratched the surface.

Brooke Gladstone: In The Post, Ellsberg, played by Matthew Reese, lays out the origins of the papers.

Matthew Reese: We were all former government guys, top clearance, all of that. McNamara wanted academics to have the chance to examine what had happened. He would say to us, "Let the chips fall where they may." I think guilt was a bigger motive and encouraged McNamara lies for all the rest, but I don't think he saw what was coming, what we'd find. It didn't even take him long to figure out, well, for us all to figure out, if the public ever saw these papers, then we'd turn against the war. Covert ops, guaranteed debt, rigged elections, it's all in there.

Brooke Gladstone: Another one of those top clearance guys was 30-year-old Les Gelb, who in 1967 was a defense department official when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara tasked him with compiling the secret history of the war, or officially the "Report of the office of the Secretary of Defense, Vietnam taskforce." Without Gelb there, there would have been no papers. When I called him in 2018, we drilled down on the impact of the Pentagon Papers, but he wasn't so sure the press got the right message. What's more, he said he rarely got the chance to set the record straight, because the Hollywood researchers didn't reach out.

Les Gelb: People behind the movie, The Post, didn't call. The only one who came by, really, was Ken Burns.

Brooke Gladstone: What did he ask you?

Les Gelb: He asked me about the origins of the Pentagon Papers, and I told him what they were. Namely, that we got a list from McNamara of 100 questions.

Brooke Gladstone: Things like what's happening in the field, how many of the enemy died.

Les Gelb: That's right, what's the body kill? 8 of the 100 questions were historical. I was given six people to work on these questions, and we were given two months to get them done. I collected the people. By the way, we were told not to tell anybody about this. We stared at the questions, and we all started laughing. They said, "Why are we doing this? This is the kind of stuff we send up to the press secretary when we're preparing him to answer questions. We're not going to be able to add anything to what we're doing on a daily basis."

Brooke Gladstone: Some of the questions were bigger than that, Les. The questions included, are we lying about the number killed in action? Can we win this war? How did the government feel about the war?

Les Gelb: I would say almost everybody in the government felt that the war was not going well, but a number felt there were ways to fight it better. There were very, very few people in the Pentagon or the State Department or the White House who were flat out against the war.

Brooke Gladstone: Right. They believed in the domino theory.

Les Gelb: Essentially that was it. That somehow if we lost the strategic place such as Berlin, we would lose Europe. In fact, one of the memos you'll see in the Pentagon Papers, the State Department referred to into China as the Asian Berlin. That's how central they thought it was to the future's security and safety of the United States. Hard to believe, but that's what we thought.

Brooke Gladstone: Why did McNamara ask you these questions if you were already given the best answers you could to the Press Secretary every day? Why?

Les Gelb: To this day, I don't know. McNamara initially just said, answer those questions. Then after this group of six that I had assembled, schmooze about it for several days, we decided, well, it might be interesting if we could look back into the files and maybe give more in-depth answers to the questions we had been answering more or less from our daily experience. Inevitably, you had to dip back into the history. We wrote up a list of about 20-some-odd monographs.

Brooke Gladstone: Short papers.

Les Gelb: That's really what the Pentagon Papers is, a bunch of short papers. I sent the memo to McNamara, and he wrote on that memo, "Okay, let it be encyclopedic, and let the chips fall where they may." We were still enjoined from telling people about it. The only ones who really knew were CIA, because McNamara called the head of the CIA, Richard Helms, and Helms shipped over to me an enormous quantity of these documents from the CIA. He never called Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State. He never called Walt Rostow, the National Security Advisor had told Lyndon Johnson the notion that this was a definitive history. It just plain wrong, Brooke, because we didn't have that kind of access, and we never were allowed to do any interviews.

Brooke Gladstone: You are a 30-year-old punk, pretty much, right?

Les Gelb: I was 30 years old. I was director of Policy Planning in the Pentagon.

Brooke Gladstone: It was your team who came up with the idea of writing these short papers, which became the Pentagon Papers. Ken Verne suggested, it's also suggested in the post that McNamara commissioned this study as a cautionary tale for those who might follow in his footsteps. What do you think of that narrative?

Les Gelb: I think it's an explanation that Bob McNamara came up with after the fact he told some people that he was doing this to save future leaders from making the same mistakes. He told others who didn't like it. For example, he told Dean Russ that he never asked for these studies, he just wanted a collection of documents.

Brooke Gladstone: How long did it take?

Les Gelb: It started in June of '67, finished in February '69. When it was all done, we had these 36 volumes, which very few people who have written about the Pentagon Papers, I assure you have read. Then I took the papers over to McNamara's office at the World Bank. He was head of the World Bank in February '69. I brought them into his office, and we're sitting around this coffee table having a little chat. Then finally I said to him, "Would you like to see the papers?" I opened up one of the boxes, handed him one of the monographs. He flipped through it like you flipp through a deck of cards with his thumb, and he threw it back into the box and he said, and I quote, "Take them back to the Pentagon."

Brooke Gladstone: Do you think he ever read them?

Les Gelb: I have no idea. I spoke to him many times over the years, and I never asked him and he never said.

Brooke Gladstone: He was replaced by Clark Clifford as Secretary of Defense, a very blue-blood lawyer who had virtually no foreign policy experience.

Les Gelb: By the way, we thought Clifford was sent to the Pentagon by Johnson to sit on people like us who had begun to ask questions about the war that the White House didn't like. Clark Clifford sensed this right away and laughed and said, "I realize I've been against this war since 1965."

Brooke Gladstone: What did he think of the domino theory?

Les Gelb: That was the reason why he became a dove in 65, long before the rest of US foreign policy experts caught in the trap of our thinking. Johnson had sent him to talk to the Asian leaders about sending more troops to fight the war, and none of them would give any troops. Clifford said, "I thought to myself, well, if the dominoes don't think they have to fight to save themselves, what the devil are we doing?"

Brooke Gladstone: By the time you were assembling what became the Pentagon Papers, it was already known, to the Secretary of Defense and to the President, and possibly to you, if you were sending that information daily to the Press Secretary, that the war was not going to be won.

Les Gelb: Yes. Well, there were some people who thought it could be won.

Brooke Gladstone: Not the President and not the Secretary of Defense.

Les Gelb: That's correct.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet they felt they had to continue to send battalion after battalion into the field to die.

Les Gelb: No question about it, but I think Walt Rostow and Dean Ross continued to believe that we still could pull this out. I think most people, by sometime in '68, came more to believe that we couldn't afford to lose.

Brooke Gladstone: They continued to send soldiers into it.

Les Gelb: Not to lose.

Brooke Gladstone: To maintain a strange balance of power in the world. The domino theory, a bankrupt notion, as it later came to be believed.

Les Gelb: At the time, most people in government believed it. The story has been put out that the Pentagon Papers showed they were all lying. While the papers show some lies, the main message is that our leaders from Truman onwards didn't know hardly anything about Vietnam and into China. They were ignorant. It also shows that foreign policy community believed that if we lost Vietnam, the rest of Asia would fall. That was a given. Here we're talking about all this stuff, and you know far more than the average informed person about the Pentagon Papers, and you're surprised by my answers.

Brooke Gladstone: That's precisely why we called you, Les, because there are popular legends about the Pentagon Papers, and you think that they convey a false narrative. Now you concede there was an enormous amount of lying about numbers, constant statements of optimism. There was the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Les Gelb: Yes, I didn't even know that, Brooke, by the way, on the Tonkin Gulf, until I saw the actual negatives of the pictures taken during the shooting.

Brooke Gladstone: Contrast, the story we were told in what you saw.

Les Gelb: What the American people were told in 1964 was that North Vietnamese boats attacked American ships in the Tonkin Gulf area, and that our ships fired back. What I found out when I actually saw the negatives of the pictures taken during that night, that showed our ships firing huge guns, and no small ships firing guns at us, I was astonished.

Brooke Gladstone: Confusion in the Gulf of Tonkin initially, and later outright deception, enabled President Johnson to effect a huge escalation in that war.

Les Gelb: That's right. It provided the public justification.

Brooke Gladstone: I would argue that you may underestimate the significance of the continuous lying throughout the conduct of that war.

Les Gelb: I don't think I underestimate the lying. I know what it was and I know who was doing it.

Brooke Gladstone: You think the media narrative about it is outsized?

Les Gelb: It's outsized based on the Pentagon Papers. Ellsberg created the myth that what the papers show is that it all was a bunch of lies. The truth is, people actually believed in the war and were ignorant about what could and could not actually be done to do well in that war. That's what you see when you actually read the papers as opposed to talk about the papers.

Brooke Gladstone: [laughs] Essentially, a set of beliefs forced the government to continue to sacrifice thousands of men in order to get the enemy to the table, maybe.

Les Gelb: Nixon negotiated for another four years or so before he concluded the deal.

Brooke Gladstone: How many people died in that period?

Les Gelb: As many as died in all the years before. The total, I think is something like 58,000 deaths. God knows how many lives ruined.

Look, I wish I had turned against the war much sooner. I regret it, you have no idea, but eventually I did. Then I spent several years of my life fighting against the Nixon policy and for the early end of the war, but it was too late.

Brooke Gladstone: How did you feel back in 1971 when you discovered that the New York Times was about to publish the Pentagon Papers?

Les Gelb: That's a very good question because to be perfectly frank, as I think I've been throughout this interview, my first instinct was that if they just hit the papers, people would think this was a definitive history of the war, which they were not, and that people would think it was all about lying rather than beliefs. Look, because we never learned that darn lesson about believing our way into these wars, we went into Afghanistan, and we went into Iraq.

Brooke Gladstone: Do you think that's why it's important to clarify what the real lesson of the Pentagon Papers is?

Les Gelb: Absolutely. We get involved in these wars, and we don't know a darn thing about those countries, the culture, the history, the politics, people on top, and even down below, and, my heavens, these are not wars like World War II and World War I, we have battalions fighting battalions, these are wars that depend on knowledge of who the people are, what the culture is like, and we jumped into them without knowing. That's the darn essential message of the Pentagon Papers.

Brooke Gladstone: Les, thank you very much.

Les Gelb: You're very welcome. It's so hard for people to swallow all this because of all these years of hearing the other story. Again, I don't deny the lies. I just want them to understand what the main points really were.

Brooke Gladstone: Les Gelb led the team that wrote the Pentagon Papers. He was also a former columnist and correspondent for the New York Times, and a long time head of the Council on Foreign Relations. He died in 2019.

Coming up, we hear from the Ink Stained Wretches. This is On the Media.

This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. In 1968, when Gelb was wrangling his team, including Ellsberg and many others, to put the secret history together, Seymour Hersh was an ambitious young freelance reporter writing for the New York Times. His big break came when he got a tip from an anti-war attorney about a soldier who shot up a bunch of civilians in Vietnam. Hersh floated that story by a general working for the army chief of staff who mentioned an army officer officer named William Calley. Armed with a name, Hersh tracked down Calley's lawyer, George Latimer, in Utah. In Lattimer's office, Hersh laid eyes on an Army indictment sheet charging Calley with the murder of "109 oriental human beings." In 2008, I spoke to Hersh about how he broke the story of My Lai, the massacre now regarded as the single most notorious atrocity of the Vietnam War.

Seymour Hersh: By the way, as soon as I saw that document, I'd like to tell you I thought, oh my God, this is going to kill the war. It's going to hurt the war effort, but really fame, fortune, glory race through my mind, what a story. I mean, this is a great story. That gave me the big start, and I figured out where Calley was. I spent a horrible long day looking for him. Finally found him.

Brooke Gladstone: You didn't know where he was?

Seymour Hersh: Oh my God, I didn't know anything. I just knew the charge sheet was written at an army base in South Carolina, and I just started looking for him. I flew that night from the West Coast via Chicago, I think, into Columbia, South Carolina, rented a car, went to the base, and at that time they were open. I just waved in, I parked my car. There was a main headquarters. It was a 30, 40 mile complex. Initially I went to every prison. There were four or five prisons, and I would just drive into the front, and I had my ready old suit on and a tie and a briefcase. I read a card, I'd get out, and there'd be some sergeant, and I'd say, "Sergeant, bring Calley out."

Brooke Gladstone: You were posing as a lawyer.

Seymour Hersh: I didn't say. If anybody asked me, I always said I was a reporter. If they made that assumption, that's fine. Of course, Calley was in any of these bases. I'm driving from one camp to another, and I went back to the main headquarters and I was stuck. Then I remembered when I worked in the Pentagon as a correspondent, the phone books are changed every three months. Calley had come back, according to the lawyer, in August. When he came back, he hadn't been charged. He was under investigation. He was just a guy coming back. I called up the information office of the base, the base telephone service. I got the chief operator, and I asked her to check the last wave of new listings in August before the new book was published in September.

It took a long time, but they finally found a William L. Calley Jr. that was listed at an engineering base 20 miles away, another one of these large army facilities. I raced over to that base, and I ran around one floor to another and couldn't see anybody. Finally, in the corner of one of the floors was a kid sleeping on a top bunk. I thought, this must be Calley. I remember kicking the bunk and waking up this blonde kid and I said, "Wake up." I said, "Calley," he said, "Who?" He was sitting there, this very young 19 year old, 20 year old kid sitting there confused, and because we are nosy, I said, "What are you doing here at three o'clock in the afternoon?" He said, "I sort the mail," and I said, "Did you ever hear of a William Calley?" He looked at me and said, "You mean the guy that shot up everybody?"

Eventually he took me to another facility where there was the senior enlisted man in charge of the male was there. Then they told me where he was. He was living, get this, the one place nobody would look for him, in the senior bachelor officer's quarters. We're talking about a place with a tennis court and a swimming pool. The last place you'd think, particularly somebody who'd been in the army like me, a potentially criminal murder first lieutenant would be stashed, but he was stashed there. I started walking through each room, knocking on doors saying, "Hey, Bill, Bill Calley." I spent maybe three or four hours doing that with no luck. I left, it was dark by now, nine, ten o'clock. There was a guy working on his car, and I went to that guy and he was a warrant officer. I said, "Calley?" He pulled himself off from under the motor, and he looked at me and he said, "You're looking for a William Calley?" I said, "Yes." He said, "He lives below me." Calley was on a boat that day. He'd gone boating. When he came in to the barracks, I was waiting for him. I said, "Are you Calley?" I'm her. She said, "Oh yes, my lawyer said you'd look me up," as if I found him so easily. This was 12, 13 hours of looking.

Brooke Gladstone: Not only did you speak to Calley, but you spoke to other people who were at the scene who were very candid about what happened?

Seymour Hersh: After I'd done the first story, I ran into this wonderful soldier. He's now dead, Ronald Ridenhour. There's a prize now given in his honor every year. Ronald Ridenhour was a soldier who learned about this right away and tried to get something done through the system without any success. He gave me a company roster, and I began to find the kids. What happened is they had been in the country, this company, Charlie Company, for about 10 or 11 weeks. They all have been told, you're going to be fighting North Vietnamese regular army. They saw nobody. They were a hundred guide strong company. They lost maybe 15 or 20 guys to snipers and bombs. They were very angry, and they were beginning to take it out on the population. They were told March 15th, tomorrow morning, you're going to meet the enemy for once.

They did what that army did. Then they toked up with their joints, and the enlisted men and officers drank. They got up at 3:30 to kill and be killed. They jumped on choppers, they go to this village, they march in looking scared to death, thinking they're going to be in a firefight. There's 500 people sitting around making breakfast, all women, old men and children. No young men of fighting age. They gather them in three ditches. Calley orders his young man to start shooting.

One was Paul Meadlo, and he shot and shot and shot. When they were all done, they sat along the ditch and had their lunch. Don't ask me how, why, and they heard a keening. One of the mothers in the bottom of the ditch had tucked a boy underneath her, two or three-year old boy, and he climbed up out of the bodies full of everybody else's blood and began to run in a panic, Calley said to Paul Meadlo, this kid from southern Indiana, "Plug him." Meadlo, one-on-one, couldn't do it, although he'd fired maybe 10 clips of 20 bullets each into the ditch. Calley, with great daring duke, took his car by and ran behind the kid and shot him in the back of the head. Everybody remembered that.

The next morning, they're on patrol, Meadlo gets his leg blown off to the knee, and they call on a helicopter to take him out. While he's waiting, he starts issuing an oath, a real oath, a chant, "God has punished me, Lieutenant Calley, and God is going to punish you. God has punished me," and the kids, when they finally began to tell me about it, and I didn't learn about this for two weeks although everybody knew this story, when one told me, they all told me. I hear this story, he lives in southern Indiana. I just dial away, and I call every exchange in Indiana. Finally, New Goshen, which is below Terre Haute, which is below Indianapolis, which is below Chicago, that's where he lives. I fly to Chicago, go to Terre Haute, get a car, go to New Goshen, and spend hours. It's a chicken farm. Meadlo is back. It's a year and a half after the incident he was shot. He's home now on this farm, rundown, chickens all over the place, a shack house. This mother walks out. I introduced myself, my ratty suit again. I said I was a reporter, I wanted to talk to him. I knew what happened. She said, "Well, he's in there." She said, "I don't know if he'll talk to you." Then she said to me, "I gave them a good boy and they sent me back a murderer."

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Journalist Seymour Hersh.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: The 20-year conflict claimed the lives of nearly 60,000 Americans and millions of Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians. We know about some of those lives lost because war correspondence risked their lives to document them, including a cadre of women reporters at a time when the military offered unfettered access to the battlefield. Members of that few, that happy few, that band of sisters, contributed to a book about their experiences titled War Torn: Stories of War from the Women Reporters Who Covered Vietnam. In 2002, I spoke to three of them. How they came to be behind the battle lines was different for each, but they each shared a compulsion as war reporters do.

Jurate Kazickas: Well, I went on a quiz show called Password to win $500. I bought a one-way ticket at that time.

Brooke Gladstone: Jurate Kazickas was born in Vilnius during World War II. Her family fled to a refugee camp, and then to America. Her parents couldn't fathom their daughter's obsession with Vietnam, quitting a nice job as a library researcher for Look Magazine.

Jurate Kazickas: My mother said to me, she said, "My whole life, our whole life has been to keep you from never having to experience a war." It really was our war. Like any journalist who went over there, I wanted to see for myself.

Brooke Gladstone: She was 24. She thought she was immortal. She stood up in the midst of battle to take pictures, and she went to Kasan, the jungle to the north near the demilitarized zone, a place of many battles but few reporters.

Jurate Kazickas: I was only there 24 hours before I was wounded mercifully, not seriously. It was a little humiliating to have shrapnel in my rear end.

Brooke Gladstone: A shrapnel in your face.

Jurate Kazickas: Yes. Fortunately, the only plastic surgeon in all of the northern part of Vietnam was on duty that day. He said, "If you were a Marine, I would just take a Brillo pad and just scrabble that stuff out of your face." He worked on me for about an hour, taking out every little piece of shrapnel.

Brooke Gladstone: In the book, Kazickas asked herself why she went out on so many patrols with the infantry. Did I really want to be a soldier? Maybe what I really wanted was to experience with another writer called The Terrible Ecstasy of War, and its horrific seduction. She recalls one colonel after hearing she was hit saying, "Well, she got what she was looking for."

Kate Webb had just set out as a journalist in Australia when she felt the pull of the war.

Kate Webb: I couldn't understand the war. There were arguments in pubs. I was in Sydney then, and the boys who were marching out were getting paint thrown at them.

Brooke Gladstone: Like Kazickas, Webb bought a one-way ticket. When she got off the plane in Saigon in March of 1967 to find a job, she was 23. Eventually, she made her way to UPI and became Cambodian bureau chief when her predecessor was killed. She covered the Tet Offensive, and over strong objections in Washington, broke the story of Cambodian leader, Lon Nol's disabling stroke. She saw many friends die. She was tough on reporters who took needless risks. Then she was taken captive by North Vietnamese troops on the south coast of Cambodia.

Kate Webb: It's one of those things that's fascinating if you live to tell it. I was able to see how the other side operated, in a limited way, of course. When you're tied up and marching all night, you don't see much.

Brooke Gladstone: How about the experience itself, what it was like simply to live as a prisoner of war?

Kate Webb: Physically, it was very tough. I lost 10 kilos in three weeks, walking all night on bare feet. That's 12 hours a night next to no food. You have to keep urging yourself on as if you're a small child. You talk to yourself and say, "Keep going."

Brooke Gladstone: Journalists like Webb and Kazickas paved the way for people like Laura Palmer, who came to the war as it was ending, but it wasn't journalism that drove her.

Laura Palmer: I literally hitchhiked to Vietnam.

Brooke Gladstone: Actually, she was hitchhiking back to Berkeley in summer school. A car stopped. She eventually hooked up with the driver, a pediatrician. He went to Vietnam, so she went too.

Laura Palmer: Haven't you ever done dumb things for love? Come on, Brooke, tell us. It was 3:00 in the morning. He was in Morocco. The phone rang. I picked it up. He said, "I got a job offer, Vietnam, six months. Do you want to go?" I said, "Sure."

Brooke Gladstone: Neither Palmer, Kazickas nor Webb had any experience covering a war when they arrived in Vietnam. When Palmer landed in 1972, women reporters had already proved themselves. When the pediatrician left and Palmer began looking for work, it was women back home who did the heavy lifting. Women reporters at the New York Times had launched a major sex discrimination suit just about the time Palmer was prospecting for a job at ABC.

Laura Palmer: Major media organizations knew they needed women on the air. I was, as the bureau chief at ABC News in Saigon, said to me on my first [crosstalk] day at work. He sat me down beside him. I was all of 22 years old. He looked at me and said, "Well, of all the applicants, you were the least qualified." That was absolutely true.

Brooke Gladstone: For Palmer, being female was by now an advantage. Some sources were more inclined to open up to a woman, but there were drawbacks as when she was offered a tour and lunch by General Minh, the commander in chief of the Saigon region. She thought they'd eat at HQ, but a table was set up in his trailer with a big double bed.

Laura Palmer: I thought, "Oh, my God. What have I walked into?" He asked me if I liked music. I said, yes, I liked the Rolling Stones, and he liked The Carpenters. Then he looked at me with all earnestness and said to me, "Miss, Laura, would you go-go for me?" [laughs]

Brooke Gladstone: She said no.

Laura Palmer: What I really wanted to say was, "You son of a bitch. People are dying under your command." This was one of the top five generals in Vietnam, and you're having lunch with me, giving me a fake Cartier lighter, and asking me to go-go for you. I thought, "There is no way if there's this much corruption at the top that they will ever win the war."

Brooke Gladstone: She did see the General again right after the evacuation of Saigon. She sat with him briefly on an aircraft carrier sailing to the Philippines.

Laura Palmer: He looked very small and very quiet, and he was chain smoking Salems and drinking Kool-Aid. I don't know, we ended up talking about Elton John. It just was one of those strange, surreal moments that happen so often in Vietnam were because of Vietnam.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Martha Gellhorn, that Veteran War reporter who cut her teeth documenting The Rise of Adolf Hitler, wrote that "Of all wars, I hated Vietnam the most because I felt personally responsible. I'm talking about what was done in South Vietnam to the people whom we supposedly had come to save, Napalmed children, destroyed villages. My complete horror remains with me as a source of grief and anger and shame that surpasses all the others."

Jurate Kazickas: This was a war like no other for everybody.

Brooke Gladstone: Jurate Kazickas.

Jurate Kazickas: To get that close to the fighting, nobody ever is numb to it. There were many people who had nervous breakdowns. There were several suicides among male reporters. It took its toll. It really did.

Brooke Gladstone: Jurate Kazickas, wounded in Kasan, is a writer who has co-authored several books on women's history. She later began a foundation to support charitable work in Lithuania where she was born.

Laura Palmer, who hitchhiked to Vietnam, continued her journalism career as an author and at Nightline on ABC News. She later worked as a pediatric hospital chaplain. In 2019, she was ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Kate Webb, who'd been taken prison in Cambodia, died in 2007.

[music]

Interview Clip: Daniel Ellsberg, at a recent press conference, you said you were willing to accept any responsibility or anything that came from your part in the Pentagon Paper. The latest indictment says 115-year prison term and $120,000 fine. Are your thoughts still the same, that you're willing to accept any consequences?

Daniel Ellsberg: How can you measure the jeopardy that I'm in to the penalty that has been paid already by 50,000 American families and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese families? It would be absolutely presumptuous of me to pity myself.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wang, and Suzanne Gaber, with help from Shaan Merchant, our technical directors, Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Josh Hahn. Special thanks to WNYC Archivist Andy Lanset. Kathy Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[music]

[00:50:41] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.